Agriculture encompasses crop and livestock production, aquaculture, fisheries, and forestry for food and non-food products. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people to live in cities. While humans started gathering grains at least 105,000 years ago, nascent farmers only began planting them around 11,500 years ago. Sheep, goats, pigs, and cattle were domesticated around 10,000 years ago. Plants were independently cultivated in at least 11 regions of the world. In the 20th century, industrial agriculture based on large-scale monocultures came to dominate agricultural output.

Agriculture in Thailand is highly competitive, diversified and specialized and its exports are very successful internationally. Rice is the country's most important crop, with some 60 percent of Thailand's 13 million farmers growing it on almost half of Thailand's cultivated land. Thailand is a major exporter in the world rice market. Rice exports in 2014 amounted to 1.3 percent of GDP. Agricultural production as a whole accounts for an estimated 9–10.5 percent of Thai GDP. Forty percent of the population work in agriculture-related jobs. The farmland they work was valued at US$2,945/rai in 2013. Most Thai farmers own fewer than eight ha (50 rai) of land.

Agriculture in Cuba has played an important part in the economy for several hundred years. Today, it contributes less than 10% to the gross domestic product (GDP), but it employs about 20% of the working population. About 30% of the country's land is used for crop cultivation.

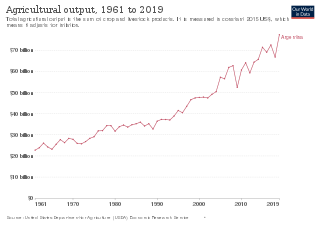

The history of agriculture in India dates back to the Neolithic period. India ranks second worldwide in farm outputs. As per the Indian economic survey 2020 -21, agriculture employed more than 50% of the Indian workforce and contributed 20.2% to the country's GDP.

Agriculture is one of the bases of Argentina's economy.

Agriculture in South Korea is a sector of the economy of South Korea. Korean agriculture is the basic industry of the Korean economy, consisting of farming, animal husbandry, forestry and fishing. At the time of its founding, Korea was a typical agricultural country, with more than 80% of the population engaged in agricultural production. After land reform under the Lee Seung-man administration, economic revitalization under the Park Chung-hee military government and the wave of world trade liberalization that began in the 1980s, Korean agriculture has undergone dramatic changes. Through the Green Revolution, Korea became self-sufficient in rice, the staple food, in 1978, and in 1996, Korea became the first Asian country after Japan to mechanize its agriculture with fine-grained cultivation. The development of Korean agriculture has also led to the development of agriculture-related industries such as fertilizer, agricultural machinery and seed.

Farming in North Korea is concentrated in the flatlands of the four west coast provinces, where a longer growing season, level land, adequate rainfall, and good irrigated soil permit the most intensive cultivation of crops. A narrow strip of similarly fertile land runs through the eastern seaboard Hamgyŏng provinces and Kangwŏn Province.

Agriculture is the largest employment sector in Bangladesh, making up 14.2 percent of Bangladesh's GDP in 2017 and employing about 42.7 percent of the workforce. The performance of this sector has an overwhelming impact on major macroeconomic objectives like employment generation, poverty alleviation, human resources development, food security, and other economic and social forces. A plurality of Bangladeshis earn their living from agriculture. Due to a number of factors, Bangladesh's labour-intensive agriculture has achieved steady increases in food grain production despite the often unfavorable weather conditions. These include better flood control and irrigation, a generally more efficient use of fertilisers, as well as the establishment of better distribution and rural credit networks.

Agriculture accounts for 22 percent of Cambodia’s GDP, and employs about 3 million people.

Agriculture in the Philippines is a major sector of the economy, ranking third among the sectors in 2022 behind only Services and Industry. Its outputs include staples like rice and corn, but also export crops such as coffee, cavendish banana, pineapple and pineapple products, coconut, sugar, and mango. The sector continues to face challenges, however, due to the pressures of a growing population. As of 2022, the sector employs 24% of the Filipino workforce and it accounted for 8.9% of the total GDP.

Angola is a potentially rich agricultural country, with fertile soils, a favourable climate, and about 57.4 million ha of agricultural land, including more than 5.0 million ha of arable land. Before independence from Portugal in 1975, Angola had a flourishing tradition of family-based farming and was self-sufficient in all major food crops except wheat. The country exported coffee and maize, as well as crops such as sisal, bananas, tobacco and cassava. By the 1990s Angola produced less than 1% the volume of coffee it had produced in the early 1970s, while production of cotton, tobacco and sugar cane had ceased almost entirely. Poor global market prices and lack of investment have severely limited the sector since independence.

Agriculture in Bhutan has a dominant role in the Bhutan's economy. In 2000, agriculture accounted for 35.9% of GDP of the nation. The share of the agricultural sector in GDP declined from approximately 55% in 1985 to 33% in 2003. Despite this, agriculture remains the primary source of livelihood for the majority of the population. Pastoralism and farming are naturally complementary modes of subsistence in Bhutan.

Agriculture employs the majority of Madagascar's population. Mainly involving smallholders, agriculture has seen different levels of state organisation, shifting from state control to a liberalized sector.

Agriculture in Kenya dominates Kenya's economy. 15–17 percent of Kenya's total land area has sufficient fertility and rainfall to be farmed, and 7–8 percent can be classified as first-class land. In 2006, almost 75 percent of working Kenyans made their living by farming, compared with 80 percent in 1980. About one-half of Kenya's total agricultural output is non-marketed subsistence production.

Agriculture in Sudan plays an important role in that country's economy. Agriculture and livestock raising are the main sources of livelihood for most of the Sudanese population. It was estimated that, as of 2011, 80 percent of the labor force were employed in that sector, including 84 percent of the women and 64 percent of the men.

Rice production in Vietnam in the Mekong and Red River deltas is important to the food supply in the country and national economy. Vietnam is one of the world's richest agricultural regions and is the second-largest exporter worldwide and the world's seventh-largest consumer of rice. The Mekong Delta is the heart of the rice-producing region of the country where water, boats, houses and markets coexist to produce a generous harvest of rice. Vietnam's land area of 33 million ha, has three ecosystems that dictate rice culture. These are the southern delta, the northern delta and the highlands of the north. The most prominent irrigated rice system is the Mekong Delta. Rice is a staple of the national diet and is seen as a "gift from God".

Agriculture in South Africa contributes around 5% of formal employment, relatively low compared to other parts of Africa and the number is still decreasing, as well as providing work for casual laborers and contributing around 2.6 percent of GDP for the nation. Due to the aridity of the land, only 13.5 percent can be used for crop production, and only 3 percent is considered high potential land.

Mozambique has a variety of regional cropping patterns; agro-climatic zones range from arid and semi-arid to the sub-humid zones to the humid highlands. The most fertile areas are in the northern and central provinces, which have high agro-ecological potential and generally produce agricultural surpluses. Southern provinces have poorer soils and scarce rainfall, and are subject to recurrent droughts and floods.

Agriculture is the main part of Tanzania's economy. As of 2016, Tanzania had over 44 million hectares of arable land with only 33 percent of this amount in cultivation. Almost 70 percent of the rich population live in rural areas, and almost all of them are involved in the farming sector. Land is a vital asset in ensuring food security, and among the nine main food crops in Tanzania are maize, sorghum, millet, rice, wheat, beans, cassava, potatoes, and bananas. The agricultural industry makes a large contribution to the country's foreign exchange earnings, with more than US$1 billion in earnings from cash crop exports.

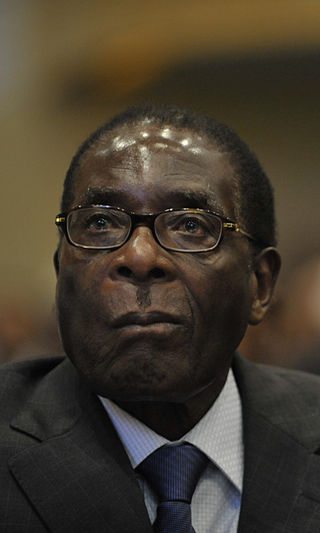

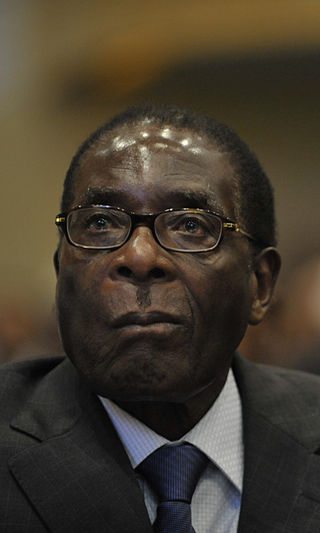

Zimbabwe has a well-established history of potato cultivation, although production levels have been declining since the 20th century due to a lack of knowledge of cultivation methods and the rising costs of farming.