The Maritimes, also called the Maritime provinces, is a region of Eastern Canada consisting of three provinces: New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. The Maritimes had a population of 1,899,324 in 2021, which makes up 5.1% of Canada's population. Together with Canada's easternmost province, Newfoundland and Labrador, the Maritime provinces make up the region of Atlantic Canada.

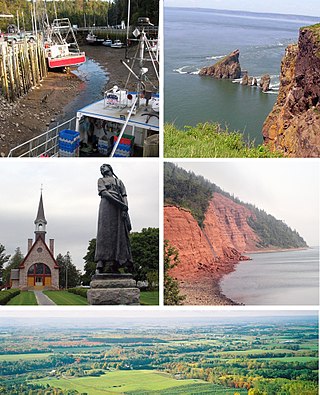

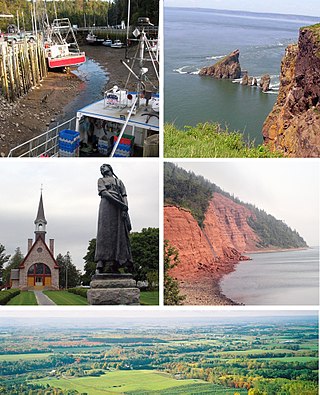

The Bay of Fundy is a bay between the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, with a small portion touching the U.S. state of Maine. It is an arm of the Gulf of Maine. Its tidal range is the highest in the world. The name is probably a corruption of the French word fendu, meaning 'split'.

Kings County is a county in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia. With a population of 62,914 in the 2021 Census, Kings County is the third most populous county in the province. It is located in central Nova Scotia on the shore of the Bay of Fundy, with its northeastern part forming the western shore of the Minas Basin.

The Mi'kmaq are a First Nations people of the Northeastern Woodlands, indigenous to the areas of Canada's Atlantic Provinces, primarily Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Newfoundland, and the Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec as well as Native Americans in the northeastern region of Maine. The traditional national territory of the Mi'kmaq is named Miꞌkmaꞌki.

The Plano cultures is a name given by archaeologists to a group of disparate hunter-gatherer communities that occupied the Great Plains area of North America during the Paleo-Indian or Archaic period.

The Maritime Archaic is a North American cultural complex of the Late Archaic along the coast of Newfoundland, the Canadian Maritimes and northern New England. The Maritime Archaic began in approximately 7000 BC and lasted until approximately 3500 BC, corresponding with the arrival of the Paleo-Eskimo groups who may have outcompeted the Maritime Archaic for resources. The culture consisted of sea-mammal hunters in the subarctic who used wooden boats. Maritime Archaic sites have been found as far south as Maine and as far north as Labrador. Their settlements included longhouses, and boat-topped temporary or seasonal houses. They engaged in long-distance trade, as shown by white chert from northern Labrador being found as far south as Maine.

Metepenagiag, also known as Red Bank is a Mi'kmaq First Nation band government in New Brunswick, Canada on the other side of the Miramichi river from Sunny Corner.

The history of New Brunswick covers the period from the arrival of the Paleo-Indians thousands of years ago to the present day. Prior to European colonization, the lands encompassing present-day New Brunswick were inhabited for millennia by the several First Nations groups, most notably the Maliseet, Mi'kmaq, and the Passamaquoddy.

Gaspereau Lake is a lake in Kings County, Nova Scotia, Canada, about 10 km south of the town of Kentville, Nova Scotia on the South Mountain. It is the largest lake in Kings County, and the fifth largest lake in Nova Scotia. The lake is shallow with dozens of forested islands and hundreds of rocky islets (skerries).

Isle Haute is an island in the upper regions of Bay of Fundy in Nova Scotia, near the entrance to the Minas Basin. It is 16 kilometers from Harbourville and eight kilometers south-southwest of Cape Chignecto. The island is part of Cumberland County, Nova Scotia and is three kilometres (1.9 mi) long and 400 metres (1,300 ft) wide. The Mi'kmaq used the island to make stone tools before Europeans arrived and called the island "Maskusetik", meaning place of wild beans, hidden oats. In 1604, Samuel de Champlain gave the present name to the island, which means "High Island" in French, when he observed the towering bluffs, timber and fresh-water springs. The steep 100 m (328 ft) basalt cliffs of the island are the result from volcanic eruptions in the Jurassic period and may have been connected to the North Mountain volcanic ridge on the mainland 200 million years ago, before the Bay of Fundy was formed.

The Debert Palaeo-Indian Site is located nearly three miles southeast of Debert, Colchester County, Nova Scotia, Canada. The Nova Scotia Museum has listed the site as a Special Place under the Special Places Protection Act. The site acquired its special status when it was discovered as the only and oldest archaeological site in Nova Scotia. The Debert site is significant to North American archaeology because it is the most North-easterly Palaeo-Indian site discovered to date. It also provides evidence for the earliest human settlements in eastern North America, which have been dated to 10,500–11,000 years ago. Additionally, this archaeological site remains one of the few Palaeo-Indian settlements to be identified within the region of North America that was once glaciated.

Cape d'Or is a headland located near Advocate, Cumberland County, on the Bay of Fundy coast of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia.

The military history of the Mi'kmaq consisted primarily of Mi'kmaq warriors (smáknisk) who participated in wars against the English independently as well as in coordination with the Acadian militia and French royal forces. The Mi'kmaq militias remained an effective force for over 75 years before the Halifax Treaties were signed (1760–1761). In the nineteenth century, the Mi'kmaq "boasted" that, in their contest with the British, the Mi'kmaq "killed more men than they lost". In 1753, Charles Morris stated that the Mi'kmaq have the advantage of "no settlement or place of abode, but wandering from place to place in unknown and, therefore, inaccessible woods, is so great that it has hitherto rendered all attempts to surprise them ineffectual". Leadership on both sides of the conflict employed standard colonial warfare, which included scalping non-combatants. After some engagements against the British during the American Revolutionary War, the militias were dormant throughout the nineteenth century, while the Mi'kmaq people used diplomatic efforts to have the local authorities honour the treaties. After confederation, Mi'kmaq warriors eventually joined Canada's war efforts in World War I and World War II. The most well-known colonial leaders of these militias were Chief (Sakamaw) Jean-Baptiste Cope and Chief Étienne Bâtard.

The Maliseet militia was made up of warriors from the Maliseet of northeastern North America. Along with the Wabanaki Confederacy, the French and Acadian militia, the Maliseet fought the British through six wars over a period of 75 years. They also mobilized against the British in the American Revolution. After confederation, Maliseet warriors eventually joined Canada's war efforts in World War I and World War II.

The Peace and Friendship Treaties were a series of written documents that the Crown of the Royal House of Stuart signed bearing the Authority of Great Britain between 1725 and 1779 under the English Crown and Throne of the Royal House of Stuart with various Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet), Abenaki, Penobscot, and Passamaquoddy peoples living in parts of what are now the Maritimes and Gaspé region in Canada and the northeastern United States. Primarily negotiated to reaffirm the peace after periods of war and to facilitate trade, these treaties remain in effect to this day.

At the end of the last Ice Age, Newfoundland and Labrador were covered in thick ice sheets. The province has had a continuous human presence for approximately 5000 years. Although Paleo-Indians are known from Nova Scotia dating back 11,000 years, no sites have been found north of the St. Lawrence. The oldest traces of human activity, in the form of quartz and quartzite knives, were discovered in 1974 in southern Labrador, but some archaeologists have speculated that a human presence may go back as much as 9000 years. Highly acidic soils have destroyed much of the bone and other organic material left behind by early humans and thus complicates archaeological research.

Humans have inhabited Quebec for 11,000 years beginning with the de-glaciated areas of the St. Lawrence River valley and expanding into parts of the Canadian Shield after glaciers retreated 5,000 years ago. Quebec has almost universally acidic soils that destroy bone and many other traces of human activity, complicating archaeological research together with development in parts of southern Quebec. Archaeological research only began in earnest in the 1960s and large parts of the province remain poorly researched.

The Maritime Peninsula is a region of eastern North America that extends from the Kennebec River in the U.S. state of Maine northeast to the Maritime provinces of Canada and Quebec's Gaspé Peninsula. It is bounded by the Gulf of Saint Lawrence to the north and the Gulf of Maine to the south.

The prehistory of New England is an important topic of research for New England archaeologists. Humans reached the current-day New England region by at least 10,500 years ago and likely earlier, occupying a recently de-glaciated environment. Pre-contact Native American groups in New England did not have full-fledged market economies and physical artifacts tended to change very slowly. However, technological shifts brought agriculture and ceramics to the region prior to the arrival of European settlers in the 17th century.