The Kingdom of the East Saxons, referred to as the Kingdom of Essex, was one of the seven traditional kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy. It was founded in the 6th century and covered the territory later occupied by the counties of Essex, Middlesex, much of Hertfordshire and west Kent. The last king of Essex was Sigered of Essex, who in 825 ceded the kingdom to Ecgberht, King of Wessex.

Rædwald, also written as Raedwald or Redwald, was a king of East Anglia, an Anglo-Saxon kingdom which included the present-day English counties of Norfolk and Suffolk. He was the son of Tytila of East Anglia and a member of the Wuffingas dynasty, who were the first kings of the East Angles. Details about Rædwald's reign are scarce, primarily because the Viking invasions of the 9th century destroyed the monasteries in East Anglia where many documents would have been kept. Rædwald reigned from about 599 until his death around 624, initially under the overlordship of Æthelberht of Kent. In 616, as a result of fighting the Battle of the River Idle and defeating Æthelfrith of Northumbria, he was able to install Edwin, who was acquiescent to his authority, as the new king of Northumbria. During the battle, both Æthelfrith and Rædwald's son, Rægenhere, were killed.

Sutton Hoo is the site of two early medieval cemeteries dating from the 6th to 7th centuries near the English town of Woodbridge. Archaeologists have been excavating the area since 1938, when a previously undisturbed ship burial containing a wealth of Anglo-Saxon artefacts was discovered. The site is important in establishing the history of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of East Anglia as well as illuminating the Anglo-Saxons during a period which lacks historical documentation.

Sæberht, Saberht or Sæbert was an Anglo-Saxon King of Essex, in succession of his father King Sledd. He is known as the first East Saxon king to have been converted to Christianity.

Prittlewell is an inner city area of Southend-on-Sea in the City of Southend-on-Sea, in the ceremonial county of Essex, England. Historically, Prittlewell is the original settlement of the city, Southend being the south end of Prittlewell. The village of Prittlewell was originally centered at the joining of three main roads, East Street, West Street, and North Street, which was extended south in the 19th century and renamed Victoria Avenue. The principal administrative buildings in Southend are located along Victoria Avenue, although Prittlewell is served by Prittlewell railway station.

The Central Museum is a museum in Southend-on-Sea, Essex, England. The museum houses collections of local and natural history and contains a planetarium constructed by astronomer Harry Ford in 1984.

The Snape Anglo-Saxon Cemetery is a place of burial dated to the 6th century AD located on Snape Common, near to the town of Aldeburgh in Suffolk, Eastern England. Dating to the early part of the Anglo-Saxon Era of English history, it contains a variety of different forms of burial, with inhumation and cremation burials being found in roughly equal proportions. The site is also known for the inclusion of a high status ship burial. A number of these burials were included within burial mounds.

Martin Oswald Hugh Carver, FSA, Hon FSA Scot, is Emeritus Professor of Archaeology at the University of York, England, director of the Sutton Hoo Research Project and a leading exponent of new methods in excavation and survey. He specialises in the archaeology of early Medieval Europe. He has an international reputation for his excavations at Sutton Hoo, on behalf of the British Museum and the Society of Antiquaries and at the Pictish monastery at Portmahomack Tarbat, Easter Ross, Scotland. He has undertaken archaeological research in England, Scotland, France, Italy and Algeria.

The A1159 road is a short road skirting the north of Southend-on-Sea from Thorpe Bay to London Southend Airport, in the coastal city of Southend-on-Sea, Essex.

Basil John Wait Brown was an English archaeologist and astronomer. Self-taught, he discovered and excavated a 6th-century Anglo-Saxon ship burial at Sutton Hoo in 1939, which has come to be called "one of the most important archaeological discoveries of all time". Although Brown was described as an amateur archaeologist, his career as a paid excavation employee for a provincial museum spanned more than thirty years.

The Dig is a historical novel by John Preston, published in May 2007, set in the context of the 1939 Anglo-Saxon ship burial excavation at Sutton Hoo, Suffolk, England. The dust jacket describes it as "a brilliantly realized account of the most famous archaeological dig in Britain in modern times".

Camp Bling was a UK-based road protest camp set up in Southend-on-Sea, Essex during September 2005 to obstruct a £25 million plan to widen the Priory Crescent section of the A1159 road over the Royal Saxon tomb in Prittlewell. In April 2009 the authority announced that plans to build the road had been abandoned and the camp was disbanded in July 2009.

The archaeology of Anglo-Saxon England is the study of the archaeology of England from the 5th Century AD to the 11th Century, when it was ruled by Germanic tribes known collectively as the Anglo-Saxons.

The Taplow Barrow is an early medieval burial mound in Taplow Court, an estate in the south-eastern English county of Buckinghamshire. Constructed in the seventh century, when the region was part of an Anglo-Saxon kingdom, it contained the remains of a deceased individual and their grave goods, now mostly in the British Museum. It is often referred to in archaeology as the Taplow burial.

Burial in Anglo-Saxon England refers to the grave and burial customs followed by the Anglo-Saxons between the mid 5th and 11th centuries CE in Early Mediaeval England. The variation of the practice performed by the Anglo-Saxon peoples during this period, included the use of both cremation and inhumation. There is a commonality in the burial places between the rich and poor – their resting places sit alongside one another in shared cemeteries. Both of these forms of burial were typically accompanied by grave goods, which included food, jewelry, and weaponry. The actual burials themselves, whether of cremated or inhumed remains, were placed in a variety of sites, including in cemeteries, burial mounds or, more rarely, in ship burials.

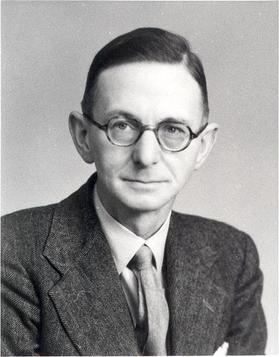

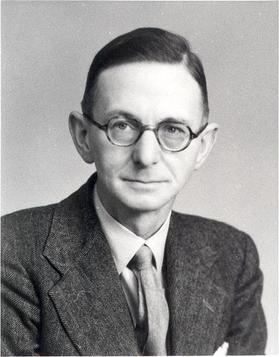

Charles Green (1901–1972) was an English archaeologist noted for his excavations in East Anglia, and his work on the Sutton Hoo ship-burial. His "signal achievements" were his East Anglian excavations, including four years spent by Caister-on-Sea and Burgh Castle, and several weeks in 1961 as Director of excavations at Walsingham Priory. Green additionally brought his "long experience of boat-handling" to bear in writing his 1963 book, Sutton Hoo: The Excavation of a Royal Ship-Burial, a major work that combined a popular account of the Anglo-Saxon burial with Green's contributions about ship-construction and seafaring.

Angela Care Evans,, is an archaeologist and former Curator in the department of Britain, Europe, and Prehistory at the British Museum. She has published extensively on the Sutton Hoo Mound 1 artefacts and early medieval metalwork.

The Harpole Treasure is a collection of Anglo-Saxon artefacts excavated at a bed burial discovered in spring 2022 in Harpole, Northamptonshire, England. It includes a necklace described as "the most ornate of its kind ever found". The Anglo-Saxon site dates to between 630 and 670 CE. The woman buried at the site is presumed to have been of high status in the early Christian church. The archaeological site is classified as a bed burial, in which the person, typically a woman of high status, was interred on top of a bed.