A duopoly is a type of oligopoly where two firms have dominant or exclusive control over a market, and most of the competition within that market occurs directly between them.

Microeconomics is a branch of economics that studies the behavior of individuals and firms in making decisions regarding the allocation of scarce resources and the interactions among these individuals and firms. Microeconomics focuses on the study of individual markets, sectors, or industries as opposed to the national economy as a whole, which is studied in macroeconomics.

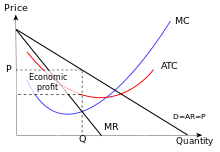

A monopoly, as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situation where a specific person or enterprise is the only supplier of a particular thing. This contrasts with a monopsony which relates to a single entity's control of a market to purchase a good or service, and with oligopoly and duopoly which consists of a few sellers dominating a market. Monopolies are thus characterised by a lack of economic competition to produce the good or service, a lack of viable substitute goods, and the possibility of a high monopoly price well above the seller's marginal cost that leads to a high monopoly profit. The verb monopolise or monopolize refers to the process by which a company gains the ability to raise prices or exclude competitors. In economics, a monopoly is a single seller. In law, a monopoly is a business entity that has significant market power, that is, the power to charge overly high prices, which is associated with a decrease in social surplus. Although monopolies may be big businesses, size is not a characteristic of a monopoly. A small business may still have the power to raise prices in a small industry.

Monopolistic competition is a type of imperfect competition such that there are many producers competing against each other, but selling products that are differentiated from one another and hence are not perfect substitutes. In monopolistic competition, a company takes the prices charged by its rivals as given and ignores the impact of its own prices on the prices of other companies. If this happens in the presence of a coercive government, monopolistic competition will fall into government-granted monopoly. Unlike perfect competition, the company maintains spare capacity. Models of monopolistic competition are often used to model industries. Textbook examples of industries with market structures similar to monopolistic competition include restaurants, cereals, clothing, shoes, and service industries in large cities. The "founding father" of the theory of monopolistic competition is Edward Hastings Chamberlin, who wrote a pioneering book on the subject, Theory of Monopolistic Competition (1933). Joan Robinson published a book The Economics of Imperfect Competition with a comparable theme of distinguishing perfect from imperfect competition. Further work on monopolistic competition was undertaken by Dixit and Stiglitz who created the Dixit-Stiglitz model which has proved applicable used in the sub fields of international trade theory, macroeconomics and economic geography.

An oligopoly is a market in which control over an industry lies in the hands of a few large sellers who own a dominant share of the market. Oligopolistic markets have homogenous products, few market participants, and inelastic demand for the products in those industries. As a result of their significant market power, firms in oligopolistic markets can influence prices through manipulating the supply function. Firms in an oligopoly are also mutually interdependent, as any action by one firm is expected to affect other firms in the market and evoke a reaction or consequential action. As a result, firms in oligopolistic markets often resort to collusion as means of maximising profits.

In economics, specifically general equilibrium theory, a perfect market, also known as an atomistic market, is defined by several idealizing conditions, collectively called perfect competition, or atomistic competition. In theoretical models where conditions of perfect competition hold, it has been demonstrated that a market will reach an equilibrium in which the quantity supplied for every product or service, including labor, equals the quantity demanded at the current price. This equilibrium would be a Pareto optimum.

In economics, imperfect competition refers to a situation where the characteristics of an economic market do not fulfil all the necessary conditions of a perfectly competitive market. Imperfect competition causes market inefficiencies, resulting in market failure. Imperfect competition usually describes behaviour of suppliers in a market, such that the level of competition between sellers is below the level of competition in perfectly competitive market conditions.

Price discrimination is a microeconomic pricing strategy where identical or largely similar goods or services are sold at different prices by the same provider in different market segments. Price discrimination is distinguished from product differentiation by the more substantial difference in production cost for the differently priced products involved in the latter strategy. Price discrimination essentially relies on the variation in the customers' willingness to pay and in the elasticity of their demand. For price discrimination to succeed, a firm must have market power, such as a dominant market share, product uniqueness, sole pricing power, etc. All prices under price discrimination are higher than the equilibrium price in a perfectly competitive market. However, some prices under price discrimination may be lower than the price charged by a single-price monopolist. Price discrimination is utilized by the monopolist to recapture some deadweight loss. This Pricing strategy enables firms to capture additional consumer surplus and maximize their profits while benefiting some consumers at lower prices. Price discrimination can take many forms and is prevalent in many industries, from education and telecommunications to healthcare.

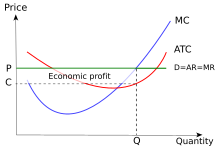

In economics, profit maximization is the short run or long run process by which a firm may determine the price, input and output levels that will lead to the highest possible total profit. In neoclassical economics, which is currently the mainstream approach to microeconomics, the firm is assumed to be a "rational agent" which wants to maximize its total profit, which is the difference between its total revenue and its total cost.

Monopoly profit is an inflated level of profit due to the monopolistic practices of an enterprise.

Allocative efficiency is a state of the economy in which production is aligned with the preferences of consumers and producers; in particular, the set of outputs is chosen so as to maximize the social welfare of society. This is achieved if every produced good or service has a marginal benefit equal to the marginal cost of production.

In economics, market power refers to the ability of a firm to influence the price at which it sells a product or service by manipulating either the supply or demand of the product or service to increase economic profit. In other words, market power occurs if a firm does not face a perfectly elastic demand curve and can set its price (P) above marginal cost (MC) without losing revenue. This indicates that the magnitude of market power is associated with the gap between P and MC at a firm's profit maximising level of output. The size of the gap, which encapsulates the firm's level of market dominance, is determined by the residual demand curve's form. A steeper reverse demand indicates higher earnings and more dominance in the market. Such propensities contradict perfectly competitive markets, where market participants have no market power, P = MC and firms earn zero economic profit. Market participants in perfectly competitive markets are consequently referred to as 'price takers', whereas market participants that exhibit market power are referred to as 'price makers' or 'price setters'.

Marginal revenue is a central concept in microeconomics that describes the additional total revenue generated by increasing product sales by 1 unit. Marginal revenue is the increase in revenue from the sale of one additional unit of product, i.e., the revenue from the sale of the last unit of product. It can be positive or negative. Marginal revenue is an important concept in vendor analysis. To derive the value of marginal revenue, it is required to examine the difference between the aggregate benefits a firm received from the quantity of a good and service produced last period and the current period with one extra unit increase in the rate of production. Marginal revenue is a fundamental tool for economic decision making within a firm's setting, together with marginal cost to be considered.

Market structure, in economics, depicts how firms are differentiated and categorised based on the types of goods they sell (homogeneous/heterogeneous) and how their operations are affected by external factors and elements. Market structure makes it easier to understand the characteristics of diverse markets.

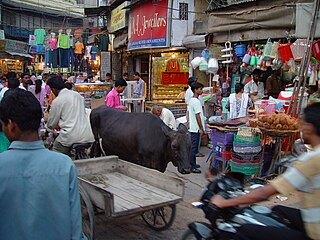

In economics, competition is a scenario where different economic firms are in contention to obtain goods that are limited by varying the elements of the marketing mix: price, product, promotion and place. In classical economic thought, competition causes commercial firms to develop new products, services and technologies, which would give consumers greater selection and better products. The greater the selection of a good is in the market, the lower prices for the products typically are, compared to what the price would be if there was no competition (monopoly) or little competition (oligopoly).

A bilateral monopoly is a market structure consisting of both a monopoly and a monopsony.

In neoclassical economics, a market distortion is any event in which a market reaches a market clearing price for an item that is substantially different from the price that a market would achieve while operating under conditions of perfect competition and state enforcement of legal contracts and the ownership of private property. A distortion is "any departure from the ideal of perfect competition that therefore interferes with economic agents maximizing social welfare when they maximize their own". A proportional wage-income tax, for instance, is distortionary, whereas a lump-sum tax is not. In a competitive equilibrium, a proportional wage income tax discourages work.

The Williamson tradeoff model is a theoretical model in the economics of industrial organization which emphasizes the tradeoff associated with horizontal mergers between gains resulting from lower costs of production and the losses associated with higher prices due to greater degree of monopoly power.

In microeconomics, the Bertrand–Edgeworth model of price-setting oligopoly looks at what happens when there is a homogeneous product where there is a limit to the output of firms which are willing and able to sell at a particular price. This differs from the Bertrand competition model where it is assumed that firms are willing and able to meet all demand. The limit to output can be considered as a physical capacity constraint which is the same at all prices, or to vary with price under other assumptions.

In microeconomics, a monopoly price is set by a monopoly. A monopoly occurs when a firm lacks any viable competition and is the sole producer of the industry's product. Because a monopoly faces no competition, it has absolute market power and can set a price above the firm's marginal cost.