Related Research Articles

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful campaign for India's independence from British rule. He inspired movements for civil rights and freedom across the world. The honorific Mahātmā, first applied to him in South Africa in 1914, is now used throughout the world.

Civil disobedience is the active, and professed refusal of a citizen to obey certain laws, demands, orders or commands of a government. By some definitions, civil disobedience has to be nonviolent to be called "civil". Hence, civil disobedience is sometimes equated with peaceful protests or nonviolent resistance. Henry David Thoreau's essay Resistance to Civil Government, published posthumously as Civil Disobedience, popularized the term in the US, although the concept itself has been practiced longer before.

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosophy of abstention from violence. It may be based on moral, religious or spiritual principles, or the reasons for it may be strategic or pragmatic. Failure to distinguish between the two types of nonviolent approaches can lead to distortion in the concept's meaning and effectiveness, which can subsequently result in confusion among the audience. Although both principled and pragmatic nonviolent approaches preach for nonviolence, they may have distinct motives, goals, philosophies, and techniques. However, rather than debating the best practice between the two approaches, both can indicate alternative paths for those who do not want to use violence.

A protest is a public act of objection, disapproval or dissent against political advantage. Protests can be thought of as acts of cooperation in which numerous people cooperate by attending, and share the potential costs and risks of doing so. Protests can take many different forms, from individual statements to mass political demonstrations. Protesters may organize a protest as a way of publicly making their opinions heard in an attempt to influence public opinion or government policy, or they may undertake direct action in an attempt to enact desired changes themselves. When protests are part of a systematic and peaceful nonviolent campaign to achieve a particular objective, and involve the use of pressure as well as persuasion, they go beyond mere protest and may be better described as civil resistance or nonviolent resistance.

Abdul Ghaffar Khan, also known as Bacha Khan or Badshah Khan, was an Indian independence activist from the North-West Frontier Province, and founder of the Khudai Khidmatgar resistance movement against British colonial rule in India.

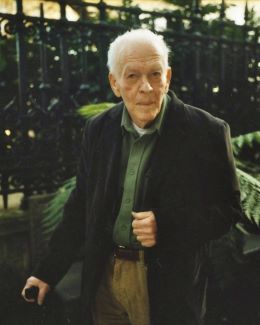

Gene Sharp was an American political scientist. He was the founder of the Albert Einstein Institution, a non-profit organization dedicated to advancing the study of nonviolent action, and professor of political science at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth. He was known for his extensive writings on nonviolent struggle, which have influenced numerous anti-government resistance movements around the world.

The Salt march, also known as the Salt Satyagraha, Dandi March, and the Dandi Satyagraha, was an act of nonviolent civil disobedience in colonial India, led by Mahatma Gandhi. The 24-day march lasted from 12 March 1930 to 6 April 1930 as a direct action campaign of tax resistance and nonviolent protest against the British salt monopoly. Another reason for this march was that the Civil Disobedience Movement needed a strong inauguration that would inspire more people to follow Gandhi's example. Gandhi started this march with 78 of his trusted volunteers. The march spanned 387 kilometres (240 mi), from Sabarmati Ashram to Dandi, which was called Navsari at that time. Growing numbers of Indians joined them along the way. When Gandhi broke the British Raj salt laws at 8:30 am on 6 April 1930, it sparked large-scale acts of civil disobedience against the salt laws by millions of Indians.

A nonviolent revolution is a revolution conducted primarily by unarmed civilians using tactics of civil resistance, including various forms of nonviolent protest, to bring about the departure of governments seen as entrenched and authoritarian without the use or threat of violence. While many campaigns of civil resistance are intended for much more limited goals than revolution, generally a nonviolent revolution is characterized by simultaneous advocacy of democracy, human rights, and national independence in the country concerned.

Hartal is a term in many Indian languages for a strike action that was first used during the Indian independence movement of the early 20th century. A hartal is a mass protest, often involving a total shutdown of workplaces, offices, shops, and courts of law, and a form of civil disobedience similar to a labour strike. In addition to being a general strike, it involves the voluntary closure of schools and places of business. It is a mode of appealing to the sympathies of a government to reverse an unpopular or unacceptable decision. A hartal is often used for political reasons, for example by an opposition party protesting against a governmental policy or action.

Gandhism is a body of ideas that describes the inspiration, vision, and the life work of Mohandas K. Gandhi. It is particularly associated with his contributions to the idea of nonviolent resistance, sometimes also called civil resistance.

"A Letter to a Hindu" was a letter written by Leo Tolstoy to Tarak Nath Das on 14 December 1908. The letter was written in response to two letters sent by Das, seeking support from the Russian author and thinker for India's independence from colonial rule. The letter was published in the Indian newspaper Free Hindustan.

Khudai Khidmatgar was an Indian, predominantly Pashtun, nonviolent resistance movement known for its activism against the British Raj in colonial India; it was based in the country's North-West Frontier Province.

Civil resistance is a form of political action that relies on the use of nonviolent resistance by ordinary people to challenge a particular power, force, policy or regime. Civil resistance operates through appeals to the adversary, pressure and coercion: it can involve systematic attempts to undermine or expose the adversary's sources of power. Forms of action have included demonstrations, vigils and petitions; strikes, go-slows, boycotts and emigration movements; and sit-ins, occupations, constructive program, and the creation of parallel institutions of government.

Nonviolent resistance, or nonviolent action, sometimes called civil resistance, is the practice of achieving goals such as social change through symbolic protests, civil disobedience, economic or political noncooperation, satyagraha, constructive program, or other methods, while refraining from violence and the threat of violence. This type of action highlights the desires of an individual or group that feels that something needs to change to improve the current condition of the resisting person or group.

Different Muslim movements through history had linked pacifism with Muslim theology. However, warfare has been an integral part of Islamic history both for the defense and the spread of the faith since the time of Muhammad.

The Politics of Nonviolent Action is a three-volume political science book by Gene Sharp, originally published in the United States in 1973. Sharp is one of the most influential theoreticians of nonviolent action, and his publications have been influential in movements around the world. This book contains his foundational analyses of the nature of political power, and of the methods and dynamics of nonviolent action. It represents a "thorough revision and rewriting" of the author's 1968 doctoral thesis at Oxford University. The book has been reviewed in professional journals and newspapers, and is mentioned on many contemporary websites. It has been fully translated into Italian and partially translated into several other languages.

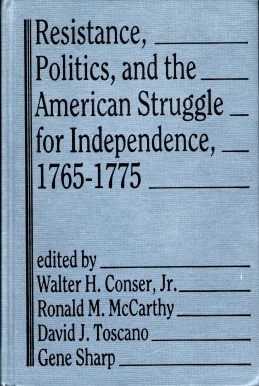

Resistance, Politics, and the American Struggle for Independence, 1765–1775 is a book that examines the role of nonviolent struggle in the period before the American Revolution. Edited by Walter H. Conser, Jr., Ronald M. McCarthy, David J. Toscano and Gene Sharp, the book was published in the United States in 1986. It argues that the Stamp Act resistance and other campaigns from 1765 to 1775 were fundamental for shaping the outcome of the struggle for American independence, and were not merely a "prelude" to armed conflict.

Gandhi as a Political Strategist is a book about the political strategies used by Mahatma Gandhi, and their ongoing implications and applicability outside of their original Indian context. Written by Gene Sharp, the book was originally published in the United States in 1979. An Indian edition was published in 1999. The book has been reviewed in several professional journals.

Direct action is a term for economic and political behavior in which participants use agency—for example economic or physical power—to achieve their goals. The aim of direct action is to either obstruct a certain practice or to solve perceived problems.

Hijra, Hijrah, Hegira, Hejira, Hijrat or Hijri are terms with multiple meanings that may refer to:

References

- 1 2 3 4 Sharp, Gene (1973). The Politics of Nonviolent Action. P. Sargent Publisher. ISBN 978-0-87558-068-5.

- ↑ Bowen, Roger W. (1984). Rebellion and Democracy in Meiji Japan: A Study of Commoners in the Popular Rights Movement. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05230-7.

- ↑ Adas, Michael (29 October 2018). State, Market and Peasant in Colonial South and Southeast Asia. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-86630-2.

- ↑ Herbst, Jeffrey (1990). "Migration, the Politics of Protest, and State Consolidation in Africa". African Affairs. 89 (355): 183–203. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a098284. ISSN 0001-9909. JSTOR 722241.

- ↑ Scott, James C.; Kerkvliet, Benedict J. Tria (19 December 2013). Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance in South-East Asia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-84532-4.

- ↑ Clements, Frank; Adamec, Ludwig W. (2003). Conflict in Afghanistan: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-402-8.

- ↑ Jolly, Surjit Kaur (2006). Reading Gandhi. Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 978-81-8069-356-4.

- ↑ Asiwaju, A. I. (1976). "Migrations as Revolt: The Example of the Ivory Coast and the Upper Volta before 1945". The Journal of African History. 17 (4): 577–594. doi:10.1017/S0021853700015073. ISSN 0021-8537. JSTOR 180740. S2CID 161799322.