| Proto-Chukotko-Kamchatkan | |

|---|---|

| Reconstruction of | Chukotko-Kamchatkan languages |

| Era | 2000 BCE |

Proto-Chukotko-Kamchatkan is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Chukotko-Kamchatkan languages. It is purported to have broken up into the Northern (Chukotian) and Southern (Itelmen) branches around 2000 BCE, when western reindeer herders moved into the Chukotko-Kamchatkans' homeland and its inland people adopted the new lifestyle. [1]

A reconstruction is presented by Michael Fortescue in his Comparative Dictionary of Chukotko-Kamchatkan (2005).

According to Fortescue, Proto-Chukotko-Kamchatkan had the following phonemes, expressed in IPA symbols.

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | *p | *t | *c | *k | *q |

| Fricative | *v | *ð | *ɣ | *ʁ | |

| Nasal | *m | *n | *ŋ | ||

| Approximant | *w | *l | *j | ||

| Rhotic | *r |

*/c/ is a true voiceless palatal stop (not the affricate č). Note that Proto-Chukotko-Kamchatkan had only voiceless stops, no voiced stops (such as /bdɡ/). However, there is a series of voiced fricatives, */vðɣʁ/. These have no voiceless counterparts (such as /fθx/).

*/v/ is a voiced labiodental fricative (like v in English). */ɣ/ is a voiced velar fricative (like the g in Dutch ogen, modern Greek gamma, Persian qāf, etc.). */ʁ/ is a voiced uvular fricative (like r in French).

The entire */tðnlr/ series is alveolar — i.e. */tðn/ are not dentals.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| Mid | e | ə | o |

| Open | æ | a |

It is generally accepted that Proto-Chukotko-Kamchatkan had an eleven-case system for nouns, but Dibella Wdzenczny has hypothesised that these evolved from only six cases in Pre-Proto-Chukotko-Kamchatkan. [1] Below is the reconstructed case system of Proto-Chukotko-Kamchatkan. [2]

| Case | Declension 1 (singular) | Declension 2 (singular) | Declension 1 (plural)1 | Declension 2 (plural) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| absolutive | -∅/-(ə)n/-ŋæ/-lŋǝn | -(ǝ)n | -t | -(ǝ)nti |

| dative | -(ǝ)ŋ | -(ǝ)naŋ | -(ǝ)ðɣǝnaŋ | |

| locative | -(ǝ)k | -(ǝ)næk | -(ǝ)ðǝk | |

| instrumental | -tæ | -(ǝ)næk | -(ǝ)ðǝk | |

| comitative | kæ--tæ | - | - | |

| associative | ka--ma | - | - | |

| referential | -kjit | -(ǝ)nækjit | -(ǝ)ðǝkækjit | |

| ablative | -ŋqo(rǝŋ) | -(ǝ)naŋqo(rǝŋ) | -(ǝ)ðǝkaŋqo(rǝŋ) | |

| vialis | -jǝpǝŋ | -(ǝ)najpǝŋ | -(ǝ)ðǝkajpǝŋ | |

| allative | -jǝtǝŋ | -(ǝ)najtǝŋ | -(ǝ)ðǝkajtǝŋ | |

| attributive | -nu | -(ǝ)nu | -(ǝ)ðɣǝnu |

1Note that the (mostly inanimate) nouns of the first declension only marked plurality in the absolutive case.

The protolanguage is thought to have been a nominative-accusative language, with the current Chukotko-Kamchatkan ergative aspects coming later in the (Northern) Chukotian branch, possibly through contact with nearby Eskimo–Aleut-speaking peoples. This would explain why Itelmen, spoken further south than any Eskimo–Aleut speakers visited, lacks ergative structures. Some linguists, however, maintain that Proto-Chukotko-Kamchatkan began as an ergative language and lost that feature over time. [3]

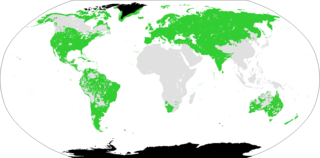

The Eskaleut, Eskimo–Aleut or Inuit–Yupik–Unangan languages are a language family native to the northern portions of the North American continent, and a small part of northeastern Asia. Languages in the family are indigenous to parts of what are now the United States (Alaska); Canada including Nunavut, Northwest Territories, northern Quebec (Nunavik), and northern Labrador (Nunatsiavut); Greenland; and the Russian Far East. The language family is also known as Eskaleutian, Eskaleutic or Inuit–Yupik–Unangan.

Nivkh, or Gilyak, or Amuric, is a small language family, often portrayed as a language isolate, of two or three mutually unintelligible languages spoken by the Nivkh people in Russian Manchuria, in the basin of the Amgun, along the lower reaches of the Amur itself, and on the northern half of Sakhalin. "Gilyak" is the Russian rendering of terms derived from the Tungusic "Gileke" and Manchu-Chinese "Gilemi" for culturally similar peoples of the Amur River region, and was applied principally to the Nivkh in Western literature.

The Paleo-Siberian languages are several language isolates and small language families spoken in parts of Siberia. They are not known to have any genetic relationship to each other; their only common link is that they are held to have antedated the more dominant languages, particularly Tungusic and latterly Turkic languages, that have largely displaced them. Even more recently, Turkic and especially Tungusic have been displaced in their turn by Russian.

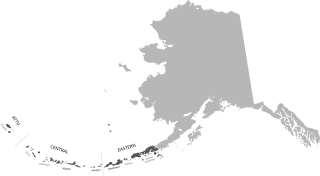

Aleut or Unangam Tunuu is the language spoken by the Aleut living in the Aleutian Islands, Pribilof Islands, Commander Islands, and the Alaska Peninsula. Aleut is the sole language in the Aleut branch of the Eskimo–Aleut language family. The Aleut language consists of three dialects, including Unalaska, Atka/Atkan, and Attu/Attuan.

The Chukotko-Kamchatkan or Chukchi–Kamchatkan languages are a language family of extreme northeastern Siberia. Its speakers traditionally were indigenous hunter-gatherers and reindeer-herders. Chukotko-Kamchatkan is endangered. The Kamchatkan branch is moribund, represented only by Western Itelmen, with only 4 or 5 elderly speakers left. The Chukotkan branch had close to 7,000 speakers left, with a reported total ethnic population of 25,000.

Eurasiatic is a hypothetical and controversial language macrofamily proposal that would include many language families historically spoken in northern, western, and southern Eurasia.

Uralo-Siberian is a hypothetical language family consisting of Uralic, Yukaghir, and Eskaleut. It was proposed in 1998 by Michael Fortescue, an expert in Eskaleut and Chukotko-Kamchatkan, in his book Language Relations across Bering Strait. Some have attempted to include Nivkh in Uralo-Siberian. Until 2011, it also included Chukotko-Kamchatkan. However, after 2011 Fortescue only included Uralic, Yukaghir and Eskaleut in the theory, although he argued that Uralo-Siberian languages have influenced Chukotko-Kamchatkan.

Proto-Uralic is the unattested reconstructed language ancestral to the modern Uralic language family. The hypothetical language is thought to have been originally spoken in a small area in about 7000–2000 BCE, and expanded to give differentiated Proto-Languages. Some newer research has pushed the "Proto-Uralic homeland" east of the Ural Mountains into Western Siberia.

Itelmen or Western Itelmen, formerly known as Western Kamchadal, is a language of the Chukotko-Kamchatkan family spoken on the western coast of the Kamchatka Peninsula. Fewer than a hundred native speakers, mostly elderly, in a few settlements in the southwest of Koryak Autonomous Okrug, remained in 1993. The 2021 Census counted 2,596 ethnic Itelmens, virtually all of whom are now monolingual in Russian. However, there are attempts to revive the language, and it is being taught in a number of schools in the region.

Kerek is an extinct language in Russia of the northern branch of the Chukotko-Kamchatkan languages. On historical linguistic grounds it is most closely related to Koryak. The next closest relative is Chukchi.

In articulatory phonetics, fortition, also known as strengthening, is a consonantal change that increases the degree of stricture. It is the opposite of the more common lenition. For example, a fricative or an approximant may become a stop. Although not as typical of sound change as lenition, fortition may occur in prominent positions, such as at the beginning of a word or stressed syllable; as an effect of reducing markedness; or due to morphological leveling.

Mosan is a hypothetical language family consisting of the Salishan, Wakashan, and Chimakuan languages of the Pacific Northwest region of North America. It was proposed by Edward Sapir in 1929 in the Encyclopædia Britannica. Little evidence has been adduced in favor of such a grouping, no progress has been made in reconstructing it, and it is now thought to reflect a language area rather than a genetic relationship. The term persists outside academic linguistic literature because of Sapir's stature.

Kamchatkan (Kamchatic) is a former dialect cluster spoken on the Kamchatka Peninsula. It now consists of a single language, Western Itelmen. It had 100 or fewer speakers in 1991, mostly of the older generation. The Russian census of 2010 still reported 80 speakers.

The phonology of the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) has been reconstructed by linguists, based on the similarities and differences among current and extinct Indo-European languages. Because PIE was not written, linguists must rely on the evidence of its earliest attested descendants, such as Hittite, Sanskrit, Ancient Greek, and Latin, to reconstruct its phonology.

Michael David Fortescue is a British-born linguist specializing in Arctic and native North American languages, including Kalaallisut, Inuktun, Chukchi and Nitinaht.

Proto-Eskaleut, Proto-Eskimo–Aleut or Proto-Inuit-Yupik-Unangan is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Eskaleut languages, family containing Eskimo and Aleut. Its existence is known through similarities in Eskimo and Aleut. The existence of Proto-Eskaleut is generally accepted among linguists. It was for a long time true that no linguistic reconstruction of Proto-Eskaleut had yet been produced, as stated by Bomhard (2008:209). Such a reconstruction was offered by Knut Bergsland in 1986. Michael Fortescue (1998:124–125) has offered another version of this system, largely based on the reconstruction of Proto-Eskimo in the Comparative Eskimo Dictionary he co-authored with Steven Jacobson and Lawrence Kaplan (1994:xi).

Proto-Eskimoan, Proto-Eskimo, or Proto-Inuit-Yupik, is the reconstructed ancestor of the Eskimo languages. It was spoken by the ancestors of the Yupik and Inuit peoples. It is linguistically related to the Aleut language, and both descend from the Proto-Eskaleut language.

The Eskimo–Uralic hypothesis posits that the Uralic and Eskimo–Aleut language families belong to a common macrofamily. It is not generally accepted by linguists because the similarities can also be merely areal features, common to unrelated language families. In 1818, the Danish linguist Rasmus Rask grouped together the languages of Greenlandic and Finnish. The Eskimo–Uralic hypothesis was put forward by Knut Bergsland in 1959. Ante Aikio stated that it's possible that there exists some connection between the two families, but exact conclusions can't be drawn and the similarities could exist by loaning.

The Proto-Italic language is the ancestor of the Italic languages, most notably Latin and its descendants, the Romance languages. It is not directly attested in writing, but has been reconstructed to some degree through the comparative method. Proto-Italic descended from the earlier Proto-Indo-European language.

This article discusses the phonology of the Chukchi language. The Chukchi language, also known as Chukot or Luorawetlan, is a language spoken by around 5 thousand people in Chukotka Autonomous Okrug. The endonym of the Chukchi language is Ԓыгъоравэтԓьэн йиԓыйиԓ , pronounced as [ɬəɣˀorawetɬˀɛn jiɬəjiɬ]. Chukchi is in the Chukotko-Kamchatkan family, and thus is closely related to Koryak, Kerek, Alyutor, and more distantly related to Itelmen, Southern Kamchadal, and Eastern Kamchadal.

{{cite book}}: |website= ignored (help)