Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is thick leathery skin with exaggerated skin markings caused by sudden itching and excessive rubbing and scratching. It generally results in small bumps, patches, scratch marks and scale. It typically affects the neck, scalp, upper eyelids, ears, palms, soles, ankles, wrists, genital areas and bottom. It often develops gradually and the scratching becomes a habit.

Itch is a sensation that causes the desire or reflex to scratch. Itches have resisted many attempts to be classified as any one type of sensory experience. Itches have many similarities to pain, and while both are unpleasant sensory experiences, their behavioral response patterns are different. Pain creates a withdrawal reflex, whereas itches leads to a scratch reflex.

Hives, also known as urticaria, is a kind of skin rash with red, raised, itchy bumps. Hives may burn or sting. The patches of rash may appear on different body parts, with variable duration from minutes to days, and does not leave any long-lasting skin change. Fewer than 5% of cases last for more than six weeks. The condition frequently recurs.

Pityriasis rosea is a type of skin rash. Classically, it begins with a single red and slightly scaly area known as a "herald patch". This is then followed, days to weeks later, by an eruption of many smaller scaly spots; pinkish with a red edge in people with light skin and greyish in darker skin. About 20% of cases show atypical deviations from this pattern. It usually lasts less than three months and goes away without treatment. Sometimes malaise or a fever may occur before the start of the rash or itchiness, but often there are few other symptoms.

Mycosis fungoides, also known as Alibert-Bazin syndrome or granuloma fungoides, is the most common form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. It generally affects the skin, but may progress internally over time. Symptoms include rash, tumors, skin lesions, and itchy skin.

Aquagenic pruritus is a skin condition characterized by the development of severe, intense, prickling-like epidermal itching without observable skin lesions and evoked by contact with water.

Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune pruritic skin disease that typically occurs in people aged over 60, that may involve the formation of blisters (bullae) in the space between the epidermal and dermal skin layers. It is classified as a type II hypersensitivity reaction, which involves formation of anti-hemidesmosome antibodies, causing a loss of keratinocytes to basement membrane adhesion.

Pemphigoid is a group of rare autoimmune blistering diseases of the skin, and mucous membranes. As its name indicates, pemphigoid is similar in general appearance to pemphigus, but, unlike pemphigus, pemphigoid does not feature acantholysis, a loss of connections between skin cells.

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP), also known as obstetric cholestasis, cholestasis of pregnancy, jaundice of pregnancy, and prurigo gravidarum, is a medical condition in which cholestasis occurs during pregnancy. It typically presents with itching and can lead to complications for both mother and fetus.

Dermatoses of pregnancy are the inflammatory skin diseases that are specific to women while they are pregnant. While some use the term 'polymorphic eruption of pregnancy' to cover these, this term is a synonym used in the UK for Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy, which is the commonest of these skin conditions.

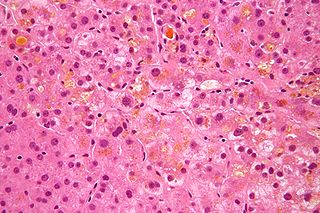

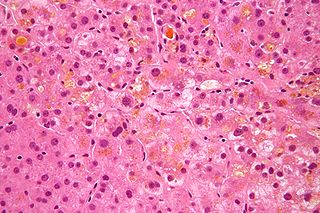

Grover's disease (GD) is a polymorphic, pruritic, papulovesicular dermatosis characterized histologically by acantholysis with or without dyskeratosis. Once confirmed, most cases of Grover's disease last six to twelve months, which is why it was originally called "transient". However it may last much longer. Nevertheless, it is not to be confused with relapsing linear acantholytic dermatosis.

Gestational pemphigoid (GP) is a rare autoimmune variant of the skin disease bullous pemphigoid, and first appears in pregnancy. It presents with tense blisters, small bumps, hives and intense itching, usually starting around the navel before spreading to limbs in mid-pregnancy or shortly after delivery. The head, face and mouth are not usually affected.

Solar urticaria (SU) is a rare condition in which exposure to ultraviolet or UV radiation, or sometimes even visible light, induces a case of urticaria or hives that can appear in both covered and uncovered areas of the skin. It is classified as a type of physical urticaria. The classification of disease types is somewhat controversial. One classification system distinguished various types of SU based on the wavelength of the radiation that causes the breakout; another classification system is based on the type of allergen that initiates a breakout.

Notalgia paresthetica or Notalgia paraesthetica (NP) (also known as "Hereditary localized pruritus", "Posterior pigmented pruritic patch", and "subscapular pruritus") is a chronic sensory neuropathy. Notalgia paresthetica is a common localized itch, affecting mainly the area between the shoulder blades (especially the T2–T6 dermatomes) but occasionally with a more widespread distribution, involving the shoulders, back, and upper chest. The characteristic symptom is pruritus (itch or sensation that makes a person want to scratch) on the back, usually on the left hand side below the shoulder blade (mid to upper back). It is occasionally accompanied by pain, paresthesia (pins and needles), or hyperesthesia (unusual or pathologically increased sensitivity of the skin to sensory stimuli, such as pain, heat, cold, or touch), which results in a well circumscribed hyperpigmentation of a skin patch in the affected area.

Neonatal acne, also known as acne neonatorum, is an acneiform eruption that occurs in newborns or infants within the first 4-6 weeks of life, and presents with open and closed comedones on the cheeks, chin and forehead.

Prurigo gestationis is an eruption consisting of pruritic, excoriated papules of the proximal limbs and upper trunk, most often occurring between the 20th and 34th week of gestation.

Pruritic folliculitis of pregnancy is a skin condition that occurs in one in 3000 people, about 0.2% of cases, who are in their second to third trimester of pregnancy where the hair follicle becomes inflamed or infected, resulting in a pus filled bump. Some dermatologic conditions aside from pruritic folliculitis during pregnancy include "pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy, atopic eruption of pregnancy, pemphigoid gestationis, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, and pustular psoriasis of pregnancy". This pruritic folliculitis of pregnancy differs from typical pruritic folliculitis; in pregnancy, it is characterized by sterile hair follicles becoming inflamed mainly involving the trunk, contrasting how typical pruritic folliculitis is mainly localized on "the upper back, shoulders, and chest." This condition was first observed after some pregnant individuals showed signs of folliculitis that were different than seen before. The inflammation was thought to be caused by hormonal imbalance, infection from bacteria, fungi, viruses or even an ingrown hair. However, there is no known definitive cause as of yet. These bumps usually begin on the belly and then spread to upper regions of the body as well as the thighs.

Senile pruritus is one of the most common conditions in the elderly or people over 65 years of age with an emerging itch that may be accompanied with changes in temperature and textural characteristics. In the elderly, xerosis, is the most common cause for an itch due to the degradation of the skin barrier over time. However, the cause of senile pruritus is not clearly known. Diagnosis is based on an elimination criteria during a full body examination that can be done by either a dermatologist or non-dermatologist physician.

Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 are characteristic signs or symptoms of the Coronavirus disease 2019 that occur in the skin. The American Academy of Dermatology reports that skin lesions such as morbilliform, pernio, urticaria, macular erythema, vesicular purpura, papulosquamous purpura and retiform purpura are seen in people with COVID-19. Pernio-like lesions were more common in mild disease while retiform purpura was seen only in critically ill patients. The major dermatologic patterns identified in individuals with COVID-19 are urticarial rash, confluent erythematous/morbilliform rash, papulovesicular exanthem, chilbain-like acral pattern, livedo reticularis and purpuric "vasculitic" pattern. Chilblains and Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children are also cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19.