Demetrius III Theos Philopator Soter Philometor Euergetes Callinicus was a Hellenistic Seleucid monarch who reigned as the King of Syria between 96 and 87 BC. He was a son of Antiochus VIII and, most likely, his Egyptian wife Tryphaena. Demetrius III's early life was spent in a period of civil war between his father and his uncle Antiochus IX, which ended with the assassination of Antiochus VIII in 96 BC. After the death of their father, Demetrius III took control of Damascus while his brother Seleucus VI prepared for war against Antiochus IX, who occupied the Syrian capital Antioch.

Euthydemus Ic. 260 BC – 200/195 BC) was a Greco-Bactrian king and founder of the Euthydemid dynasty. He is thought to have originally been a satrap of Sogdia, who usurped power from Diodotus II in 224 BC. Literary sources, notably Polybius, record how he and his son Demetrius resisted an invasion by the Seleucid king Antiochus III from 209 to 206 BC. Euthydemus expanded the Bactrian territory into Sogdia, constructed several fortresses, including the Derbent Wall in the Iron Gate, and issued a very substantial coinage.

Diodotus I Soter was the first Hellenistic king of Bactria. Diodotus was initially satrap of Bactria, but became independent of the Seleucid empire around 255 BCE, establishing the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom. In about 250 BCE, Diodotus repelled a Parthian invasion of Bactria by Arsaces. He minted an extensive coinage and administered a powerful and prosperous new kingdom. He died around 235 BCE and was succeeded by his son Diodotus II.

Alexander II Theos Epiphanes Nikephoros was a Hellenistic Seleucid monarch who reigned as the King of Syria between 128 BC and 123 BC. His true parentage is debated; depending on which ancient historian, he either claimed to be a son of Alexander I or an adopted son of Antiochus VII. Most ancient historians and the modern academic consensus maintain that Alexander II's claim to be a Seleucid was false. His surname "Zabinas" (Ζαβίνας) is a Semitic name that is usually translated as "the bought one". It is possible, however, that Alexander II was a natural son of Alexander I, as the surname can also mean "bought from the god". The iconography of Alexander II's coinage indicates he based his claims to the throne on his descent from Antiochus IV, the father of Alexander I.

Philip I Epiphanes Philadelphus was a Hellenistic Seleucid monarch who reigned as the king of Syria from 94 to either 83 or 75 BC. The son of Antiochus VIII and his wife Tryphaena, he spent his early life in a period of civil war between his father and his uncle Antiochus IX. The conflict ended with the assassination of Antiochus VIII; Antiochus IX took power in the Syrian capital Antioch, but soon fell in battle with Antiochus VIII's eldest son Seleucus VI.

Seleucus VI Epiphanes Nicator was a Hellenistic Seleucid monarch who ruled Syria between 96 and 94 BC. He was the son of Antiochus VIII and his Ptolemaic Egyptian wife Tryphaena. Seleucus VI lived during a period of civil war between his father and his uncle Antiochus IX, which ended in 96 BC when Antiochus VIII was assassinated. Antiochus IX then occupied the capital Antioch while Seleucus VI established his power-base in western Cilicia and himself prepared for war. In 95 BC, Antiochus IX marched against his nephew, but lost the battle and was killed. Seleucus VI became the master of the capital but had to share Syria with his brother Demetrius III, based in Damascus, and his cousin, Antiochus IX's son Antiochus X.

The history of ancient Greek coinage can be divided into four periods: the Archaic, the Classical, the Hellenistic and the Roman. The Archaic period extends from the introduction of coinage to the Greek world during the 7th century BC until the Persian Wars in about 480 BC. The Classical period then began, and lasted until the conquests of Alexander the Great in about 330 BC, which began the Hellenistic period, extending until the Roman absorption of the Greek world in the 1st century BC. The Greek cities continued to produce their own coins for several more centuries under Roman rule. The coins produced during this period are called Roman provincial coins or Greek Imperial Coins.

Diodotus II Theos was the son and successor of Diodotus I Soter, who rebelled against the Seleucid empire, establishing the Graeco-Bactrian Kingdom. Diodotus II probably ruled alongside his father as co-regent, before succeeding him as sole king around 235 BC. He prevented Seleucid efforts to reincorporate Bactria back into the empire, by allying with the Parthians against them. He was murdered around 225 BC by Euthydemus I, who succeeded him as king.

Cleopatra Selene was the Queen consort of Egypt from 115 to 102 BC, the Queen consort of Syria from 102 to 92 BC, and the monarch of Syria from 82 to 69 BC. The daughter of Ptolemy VIII Physcon and Cleopatra III of Egypt, Cleopatra Selene was favoured by her mother and became a pawn in Cleopatra III's political manoeuvres. In 115 BC, Cleopatra III forced her son Ptolemy IX to divorce his sister-wife Cleopatra IV, and chose Cleopatra Selene as the new queen consort of Egypt. Tension between the king and his mother grew and ended with his expulsion from Egypt, leaving Cleopatra Selene behind; she probably then married the new king, her other brother Ptolemy X.

Silver coins are one of the oldest mass-produced form of coinage. Silver has been used as a coinage metal since the times of the Greeks; their silver drachmas were popular trade coins. The ancient Persians used silver coins between 612–330 BC. Before 1797, British pennies were made of silver.

The cistophorus was a coin of ancient Pergamum. It was introduced shortly before 190 B.C. at that city to provide the Attalid kingdom with a substitute for Seleucid coins and the tetradrachms of Philetairos. It also came to be used by a number of other cities that were under Attalid control. These cities included Alabanda and Kibyra. It continued to be minted and circulated by the Romans with different coin types and legends, but the same weight down to the time of Hadrian, long after the kingdom was bequeathed to Rome. It owes its name to a figure, on the obverse, of the sacred chest of Dionysus.

The Achaemenid Empire issued coins from 520 BC–450 BC to 330 BC. The Persian daric was the first gold coin which, along with a similar silver coin, the siglos represented the first bimetallic monetary standard. It seems that before the Persians issued their own coinage, a continuation of Lydian coinage under Persian rule is likely. Achaemenid coinage includes the official imperial issues, as well as coins issued by the Achaemenid provincial governors (satraps), such as those stationed in Asia Minor.

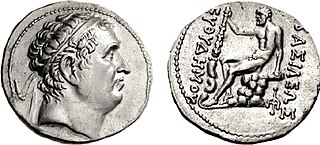

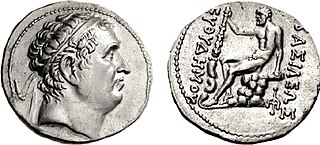

The coinage of the Seleucid Empire is based on the coins of Alexander the Great, which in turn were based on Athenian coinage of the Attic weight. Many mints and different issues are defined, with mainly base and silver coinage being in abundance. A large concentration of mints existed in the Seleucid Syria, as the Mediterranean parts of the empire were more reliant on coinage in economic function.

The tetradrachm was a large silver coin that originated in Ancient Greece. It was nominally equivalent to four drachmae. Over time the tetradrachm effectively became the standard coin of the Antiquity, spreading well beyond the borders of the Greek World. As a result, tetradrachms were minted in vast quantities by various polities in many weight and fineness standards, though the Athens-derived Attic standard of about 17.2 grams was the most common.

The Yehud coinage is a series of small silver coins bearing the Aramaic inscription Yehud. They derive their name from the inscription YHD (𐤉𐤄𐤃), "Yehud", the Aramaic name of the Achaemenid Persian province of Yehud; others are inscribed YHDH, the same name in Hebrew. The minting of Yehud coins commenced around the middle of the fourth century BC, and continued until the end of the Ptolemaic period.

In ancient Greece, the drachma was an ancient currency unit issued by many city-states during a period of ten centuries, from the Archaic period throughout the Classical period, the Hellenistic period up to the Roman period. The ancient drachma originated in the Greece around the 6th century BC. The coin, usually made of silver or sometimes gold had its origins in a bartering system that referred to a drachma as a handful of wooden spits or arrows. The drachma was unique to each city state that minted them, and were sometimes circulated all over the Mediterranean. The coinage of Athens was considered to be the strongest and became the most popular.

Attic weight, or the Attic standard, also known as Euboic standard, was one of the main monetary standards in ancient Greece. As a result of its use in the coinage of the Athenian empire and the empire of Alexander the Great, it was the dominant weight standard for coinage issued in the Eastern Mediterranean from the fifth century BC until the introduction of the Roman denarius to the region in the late first century BC.

Bithynian coinage refers to coinage struck by the Kingdom of Bithynia that was situated on the coast of the Black Sea.

Ancient Rhodian coinage refers to the coinage struck by an independent Rhodian polity during Classical and Hellenistic eras. The Rhodians also controlled territory on neighbouring Caria that was known as Rhodian Peraia under the islanders' rule. However, many other eastern Mediterranean states and polities adopted the Rhodian (Chian) monetary standard following Rhodes. Coinage using the standard achieved a wide circulation in the region. Even the Ptolemaic Kingdom, a major Hellenistic state in the eastern Mediterranean, briefly adopted the Rhodian monetary standard.