Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi, known mononymously as Donatello, was an Italian sculptor of the Renaissance period. Born in Florence, he studied classical sculpture and used his knowledge to develop an Early Renaissance style of sculpture. He spent time in other cities, where he worked on commissions and taught others; his periods in Rome, Padua, and Siena introduced to other parts of Italy the techniques he had developed in the course of a long and productive career. His David was the first freestanding nude male sculpture since antiquity; like much of his work it was commissioned by the Medici family.

Jacopo della Quercia, also known as Jacopo di Pietro d'Agnolo di Guarnieri, was an Italian sculptor of the Renaissance, a contemporary of Brunelleschi, Ghiberti and Donatello. He is considered a precursor of Michelangelo.

Andrea Pisano also known as Andrea da Pontedera, was an Italian sculptor and architect.

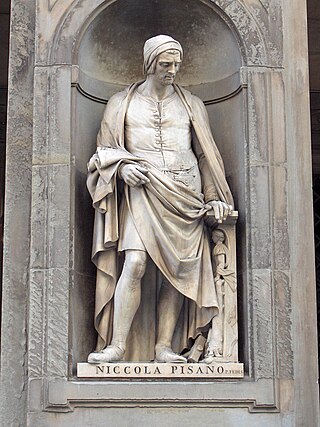

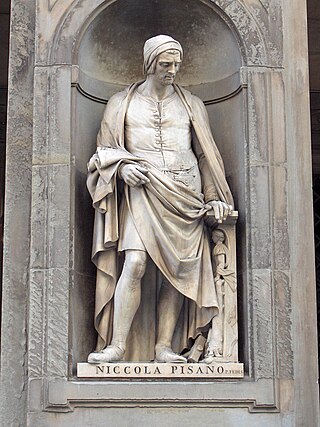

Nicola Pisano was an Italian sculptor whose work is noted for its classical Roman sculptural style. Pisano is sometimes considered to be the founder of modern sculpture.

Giovanni Pisano was an Italian sculptor, painter and architect, who worked in the cities of Pisa, Siena and Pistoia. He is best known for his sculpture which shows the influence of both the French Gothic and the Ancient Roman art. Henry Moore, referring to his statues for the facade of Siena Cathedral, called him "the first modern sculptor".

Siena Cathedral is a medieval church in Siena, Italy, dedicated from its earliest days as a Roman Catholic Marian church, and now dedicated to the Assumption of Mary.

The Piazza dei Miracoli, formally known as Piazza del Duomo, is a walled 8.87-hectare (21.9-acre) compound in central Pisa, Tuscany, Italy, recognized as an important center of European medieval art and one of the finest architectural complexes in the world. It was all owned by the Catholic Church and is dominated by four great religious edifices: Pisa Cathedral, the Pisa Baptistery, the Leaning Tower of Pisa, and the Camposanto Monumentale. Partly paved and partly grassed, the Piazza dei Miracoli is also the site of the Ospedale Nuovo di Santo Spirito, which now houses the Sinopias Museum and the Cathedral Museum.

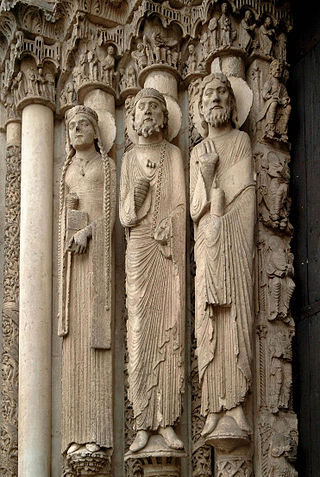

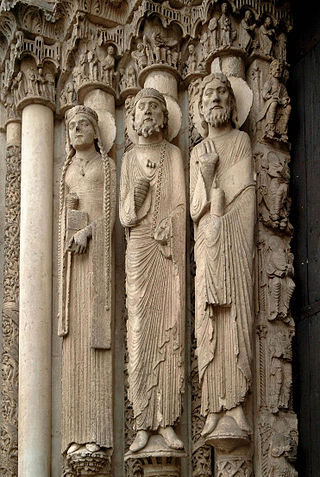

Gothic art was a style of medieval art that developed in Northern France out of Romanesque art in the 12th century AD, led by the concurrent development of Gothic architecture. It spread to all of Western Europe, and much of Northern, Southern and Central Europe, never quite effacing more classical styles in Italy. In the late 14th century, the sophisticated court style of International Gothic developed, which continued to evolve until the late 15th century. In many areas, especially Germany, Late Gothic art continued well into the 16th century, before being subsumed into Renaissance art. Primary media in the Gothic period included sculpture, panel painting, stained glass, fresco and illuminated manuscripts. The easily recognizable shifts in architecture from Romanesque to Gothic, and Gothic to Renaissance styles, are typically used to define the periods in art in all media, although in many ways figurative art developed at a different pace.

Giotto's Campanile is a free-standing campanile that is part of the complex of buildings that make up Florence Cathedral on the Piazza del Duomo in Florence, Italy.

The Pisa Baptistery of St. John is a Roman Catholic ecclesiastical building in Pisa, Italy. Construction started in 1152 to replace an older baptistery, and when it was completed in 1363, it became the second building, in chronological order, in the Piazza dei Miracoli, near the Duomo di Pisa and the cathedral's free-standing campanile, the famous Leaning Tower of Pisa. The baptistery was designed by Diotisalvi, whose signature can be read on two pillars inside the building, with the date 1153.

The Arca di San Domenico is a monument containing the remains of Saint Dominic. It is located in Dominic’s Chapel in the Basilica of San Domenico in Bologna, Italy.

Orvieto Cathedral is a large 14th-century Roman Catholic cathedral dedicated to the Assumption of the Virgin Mary and situated in the town of Orvieto in Umbria, central Italy. Since 1986, the cathedral in Orvieto has been the episcopal seat of the former Diocese of Todi as well.

Pisa Cathedral is a medieval Catholic cathedral dedicated to the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, in the Piazza dei Miracoli in Pisa, Italy, the oldest of the three structures in the plaza followed by the Pisa Baptistry and the Campanile known as the Leaning Tower of Pisa. The cathedral is a notable example of Romanesque architecture, in particular the style known as Pisan Romanesque. Consecrated in 1118, it is the seat of the Archbishop of Pisa. Construction began in 1063 and was completed in 1092. Additional enlargements and a new facade were built in the 12th century and the roof was replaced after damage from a fire in 1595.

The pulpit in the pieve of Sant'Andrea, Pistoia, Italy is a masterpiece by the Italian sculptor Giovanni Pisano, completed in 1301. It has many similarities with the groundbreaking pulpit in the Pisa Baptistery of 1260 by Giovanni's father Nicola Pisano, which was followed by the Siena Cathedral Pulpit, which Giovanni had assisted with.

Duecento or Dugento is the Italian word for the Italian culture of the 13th century - that is to say 1200 to 1299. During this period the first shoots of the Italian Renaissance appeared, in literature and art, to be developed in the following trecento period.

The Siena Cathedral Pulpit is an octagonal structure in Siena Cathedral sculpted by Nicola Pisano and his assistants Arnolfo di Cambio, Lapo di Ricevuto, and Nicolas' son Giovanni Pisano between the fall of 1265 and the fall of 1268. The pulpit, with its seven narrative panels and nine decorative columns carved out of Carrara marble, showcases Nicola Pisano's talent for integrating classical themes into Christian traditions, making both Nicola Pisano and the Siena pulpit forerunners of the classical revival of the Italian Renaissance.

Volterra Cathedral is a Roman Catholic cathedral in Volterra, Italy, dedicated to the Assumption of the Virgin Mary. It is the seat of the bishop of Volterra.

The St John Altarpiece is a c. 1455 oil-on-oak wood panel altarpiece by the Early Netherlandish painter Rogier van der Weyden, now in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. The triptych is linked to the artist's earlier Miraflores Altarpiece in its symbolic motifs, format and intention.

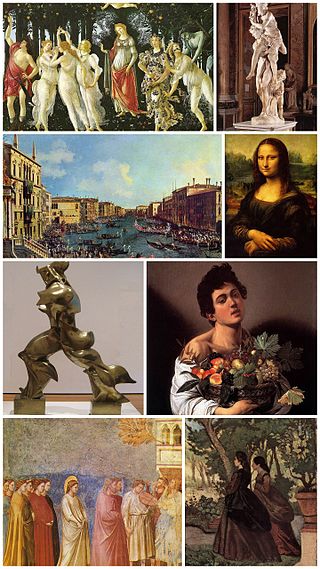

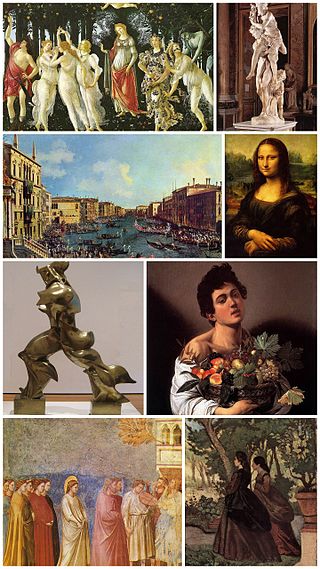

Italian Renaissance sculpture was an important part of the art of the Italian Renaissance, in the early stages arguably representing the leading edge. The example of Ancient Roman sculpture hung very heavily over it, both in terms of style and the uses to which sculpture was put. In complete contrast to painting, there were many surviving Roman sculptures around Italy, above all in Rome, and new ones were being excavated all the time, and keenly collected. Apart from a handful of major figures, especially Michelangelo and Donatello, it is today less well-known than Italian Renaissance painting, but this was not the case at the time.

Renaissance sculpture is understood as a process of recovery of the sculpture of classical antiquity. Sculptors found in the artistic remains and in the discoveries of sites of that bygone era the perfect inspiration for their works. They were also inspired by nature. In this context we must take into account the exception of the Flemish artists in northern Europe, who, in addition to overcoming the figurative style of the Gothic, promoted a Renaissance foreign to the Italian one, especially in the field of painting. The rebirth of antiquity with the abandonment of the medieval, which for Giorgio Vasari "had been a world of Goths", and the recognition of the classics with all their variants and nuances was a phenomenon that developed almost exclusively in Italian Renaissance sculpture. Renaissance art succeeded in interpreting Nature and translating it with freedom and knowledge into a multitude of masterpieces.