Related Research Articles

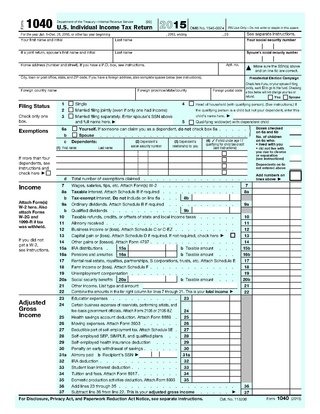

The United States of America has separate federal, state, and local governments with taxes imposed at each of these levels. Taxes are levied on income, payroll, property, sales, capital gains, dividends, imports, estates and gifts, as well as various fees. In 2020, taxes collected by federal, state, and local governments amounted to 25.5% of GDP, below the OECD average of 33.5% of GDP.

Andrew Chi-Chih Yao is a Chinese computer scientist and computational theorist. He is currently a professor and the dean of Institute for Interdisciplinary Information Sciences (IIIS) at Tsinghua University. Yao used the minimax theorem to prove what is now known as Yao's Principle.

The United States federal government and most state governments impose an income tax. They are determined by applying a tax rate, which may increase as income increases, to taxable income, which is the total income less allowable deductions. Income is broadly defined. Individuals and corporations are directly taxable, and estates and trusts may be taxable on undistributed income. Partnerships are not taxed, but their partners are taxed on their shares of partnership income. Residents and citizens are taxed on worldwide income, while nonresidents are taxed only on income within the jurisdiction. Several types of credits reduce tax, and some types of credits may exceed tax before credits. Most business expenses are deductible. Individuals may deduct certain personal expenses, including home mortgage interest, state taxes, contributions to charity, and some other items. Some deductions are subject to limits, and an Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) applies at the federal and some state levels.

Renunciation of citizenship is the voluntary loss of citizenship. It is the opposite of naturalization, whereby a person voluntarily obtains citizenship. It is distinct from denaturalization, where citizenship is revoked by the state.

Vance v. Terrazas, 444 U.S. 252 (1980), was a United States Supreme Court decision that established that a United States citizen cannot have their citizenship taken away unless they have acted with an intent to give up that citizenship. The Supreme Court overturned portions of an act of Congress which had listed various actions and had said that the performance of any of these actions could be taken as conclusive, irrebuttable proof of intent to give up U.S. citizenship. However, the Court ruled that a person's intent to give up citizenship could be established through a standard of preponderance of evidence — rejecting an argument that intent to relinquish citizenship could only be found on the basis of clear, convincing and unequivocal evidence.

Citizenship of the United States is a legal status that entails Americans with specific rights, duties, protections, and benefits in the United States. It serves as a foundation of fundamental rights derived from and protected by the Constitution and laws of the United States, such as freedom of expression, due process, the rights to vote, live and work in the United States, and to receive federal assistance.

An expatriation tax or emigration tax is a tax on persons who cease to be tax-resident in a country. This often takes the form of a capital gains tax against unrealised gain attributable to the period in which the taxpayer was a tax resident of the country in question. In most cases, expatriation tax is assessed upon change of domicile or habitual residence; in the United States, which is one of only three countries to substantively tax its overseas citizens, the tax is applied upon relinquishment of American citizenship, on top of all taxes previously paid. Australia has "Deemed disposal tax" which in essence is exit tax.

The Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) is a 2010 U.S. federal law requiring all non-U.S. foreign financial institutions (FFIs) to search their records for customers with indicia of a connection to the U.S., including indications in records of birth or prior residency in the U.S., or the like, and to report such assets and identities of such persons to the United States Department of the Treasury. FATCA also requires such persons to report their non-U.S. financial assets annually to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) on form 8938, which is in addition to the older and further redundant requirement to report them annually to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) on form 114. Like U.S. income tax law, FATCA applies to U.S. residents and also to U.S. citizens and green card holders residing in other countries.

Roman Mykhailovych Zvarych is a Ukrainian politician. A former United States citizen, he was one of the first people to relinquish that citizenship in order to take up Ukrainian citizenship after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Lee Seung-Jun is an American-born South Korean professional basketball player. He last played for Alab Pilipinas of the ASEAN Basketball League.

Diane Lee Ching-an is a Taiwanese former politician. She naturalized as a U.S. citizen in 1991, but later relinquished U.S. citizenship. Lee, a Kuomintang member, held elected public office in Taiwan from 1994 to 2009, first as a Taipei City Councilwoman and then for three terms as a legislator representing Daan District, Taipei City.

The Reed Amendment, also known as the Expatriate Exclusion Clause, created a provision of United States federal law attempting to impose an entry ban on certain former U.S. citizens based on their reasons for renouncing U.S. citizenship. Notably, entry can be denied to persons who renounced their U.S. citizenship to avoid paying income taxes. The United States is one of two countries in the world that taxes its citizens' income earned abroad for citizens whose primary residence is abroad. The other country to do so is Eritrea.

The Ex-PATRIOT Act was a proposed United States federal law to raise taxes and impose entry bans on certain former citizens and departing permanent residents. The law would automatically classify all people who relinquished U.S. citizenship or permanent residence in the decade prior to the law's passage or any future year as having "tax avoidance intent" if they met certain asset or tax liability thresholds or had failed to file any required federal tax forms within the preceding five years. People determined to have "tax avoidance intent", referred to in the text of the law as specified expatriates, would be affected in two ways. First, they would have to pay 30% capital gains tax on any U.S. property sold after the law's enactment. Second, they would be barred from re-entry into the U.S. either under immigrant or non-immigrant categories.

Chris Moonkey Nam was a South Korean businessman and past Korean American community leader. A former citizen of the United States by naturalisation, he renounced U.S. citizenship in 2011 in order to pursue his political ambitions in his country of birth.

Alexis Zook Jeffers is a Saint Kitts and Nevis politician with the Concerned Citizens' Movement. He represents the Saint James constituency in the Nevis Island Assembly, and has also stood as a candidate for election to the National Assembly.

The Renunciation Act of 1944 was an act of the 78th Congress regarding the renunciation of United States citizenship. Prior to the law's passage, it was not possible to lose U.S. citizenship while in U.S. territory except by conviction for treason; the Renunciation Act allowed people physically present in the U.S. to renounce citizenship when the country was in a state of war by making an application to the Attorney General. The intention of the 1944 Act was to encourage Japanese American internees to renounce citizenship so that they could be deported to Japan.

Lists of former United States citizens cover citizens of the United States who were denaturalized, or stripped of their nationality, and citizens who chose to relinquish their nationality.

Roger Keith Ver is an early investor in Bitcoin, Bitcoin-related startups and an early promoter of Bitcoin. Ver has sometimes been referred to as "Bitcoin Jesus". He now primarily promotes Bitcoin Cash as Ver sees it as fulfilling the intended and original purpose of the "Bitcoin White Paper", first published in 2009 by Satoshi Nakamoto, in which Nakamoto referred to Bitcoin as a peer-to-peer electronic cash system.

An accidental American is someone whom US law deems to be an American citizen, but who has only a tenuous connection with that country. For example, American nationality law provides that anyone born on US territory is a US citizen, including those who leave as infants or young children, even if neither parent is a US citizen. US law also ascribes American citizenship to some children born abroad to a US citizen parent, even if those children never enter the United States. Since the early 2000s, the term "accidental American" has been adopted by several activist groups to protest tax treaties and Inter-Governmental Agreements which treat such people as American citizens who are therefore potentially subject to tax and financial reporting requirements – requirements which few other countries impose on their nonresident citizens. Accidental Americans may be unaware of these requirements, or their US citizen status, until they encounter problems accessing bank services in their home countries, for example, or are barred from entering the US on a non-US passport. Furthermore, the US State Department now charges USD 2350 to renounce citizenship, while tax reporting requirements associated with legal expatriation may pose additional financial burdens.

Under United States federal law, a U.S. citizen or national may voluntarily and intentionally give up that status and become an alien with respect to the United States. Relinquishment is distinct from denaturalization, which in U.S. law refers solely to cancellation of illegally procured naturalization.

References

- ↑ "외국인학교 입학 위해 '국적세탁'…부유층 100여 명 확인". Dong-A Ilbo . September 12, 2012. Retrieved February 13, 2014.

- ↑ Kirsch, Michael S. (2004). "Alternative Sanctions and the Federal Tax Law: Symbols, Shaming, and Social Norm Management as a Substitute for Effective Tax Policy". Iowa Law Review. 89 (863). SSRN 552730.

- ↑ Fraser, Erin L. (July 2017). "The Roots and Fruits of Section 6039G" (PDF). California Tax Lawyer. 26 (3): 40. SSRN 2827716. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 18, 2019. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- ↑ Kirsch 2004 , p. 889

- ↑ Issues Presented By Proposals To Modify The Tax Treatment Of Expatriation. Joint Committee on Taxation. June 1, 1995.

- ↑ Kirsch 2004 , pp. 889–890

- 1 2 3 Newman, Barry (December 28, 1998). "Renouncing U.S. Citizenship Becomes Harder Than Ever". Wall Street Journal.

- 1 2 Ashby, Cornelia M. (May 1, 2000). Information Concerning Tax-Motivated Expatriation (PDF). General Accounting Office. p. 3. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ↑ Wood, Robert (May 3, 2014). "Record Numbers Renounce U.S. Citizenship — And Many Aren't Counted". Forbes. Retrieved May 29, 2014.

- ↑ Saunders, Laura (August 2, 2012). "The Renouncers: Who Gave Up U.S. Citizenship, and Why?". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- 1 2 Kirsch 2004 , pp. 906–909

- 1 2 3 4 "FBI and IRS differ on U.S. citizenship data". Advisor.ca. Rogers Media. February 16, 2013. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- ↑ Cain, Patrick; Mehler Paperny, Anna; Young, Leslie (August 17, 2013). "Why are so many American expats giving up citizenship? It's a taxing issue". Global News . Retrieved August 17, 2013.

- ↑ Gaver, John (2012). The Rich Don't Pay Tax! ... Or Do They?. Alliance Books. ISBN 9780615624372.

- ↑ "Quarterly List of Expatriates: Source of Data". International Tax Blog. Andrew Mitchel LLC, Attorneys at Law. February 12, 2014. Retrieved February 13, 2014.

- ↑ Kirsch 2004 , p. 890

- ↑ William J. Krouse, Congressional Research Service (March 31, 2000). Issues Relating to Excluding Tax-motivated Expatriates under Section 212(a)(10)(E) of The Immigration and Nationality Act (PDF). p. A-14. Retrieved June 26, 2015.

- ↑ "Record Numbers Renounce U.S. Citizenship—And Many Aren't Counted". Forbes. May 3, 2014. Retrieved May 15, 2015.

- ↑ "Request for Guidance on the Tax Status of Certain Expatriates" (PDF). American Bar Association, Section of Taxation. March 2, 2015. Retrieved June 5, 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Tax Court Confirms It — 'Informal' Relinquishment of Green Card Not Enough". Angloinfo. October 12, 2014. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ↑ "Is the IRS Undercounting Americans Renouncing U.S. Citizenship?". Wall Street Journal. September 16, 2015. Retrieved September 21, 2015.

- ↑ Ashby 2000 , p. 4

- ↑ Fraser 2017 , p. 39

- ↑ "National Instant Criminal Background Check System: Fact Sheet". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- ↑ John W. Magaw (June 27, 1997). "Definitions for the Categories of Persons Prohibited From Receiving Firearms (95R-051P)". Federal Register. 62 (124): 34634–34640. Retrieved August 13, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Cain, Patrick (February 12, 2014). "U.S. list of ex-citizens full of errors, duplication". Global News. Retrieved February 13, 2014.

- ↑ "More than 3,100 Americans renounced citizenship last year: FBI". Global News. January 10, 2014. Retrieved February 13, 2014.

- ↑ Laura Dawkins, Chief, Regulatory Coordination Division, Office of Policy and Strategy, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Department of Homeland Security (January 24, 2014). "Agency Information Collection Activities: Record of Abandonment of Lawful Permanent Resident Status, Form I-407; Existing Collection In Use Without an OMB Control Number". Federal Register. 79: 4169. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- ↑ Maura Harty, Assistant Secretary, Bureau of Consular Affairs, Department of State (August 3, 2007). "30-Day Notice of Proposed Information Collection: DS 4079, Questionnaire-Information for Determining Possible Loss of United States Citizenship". Federal Register. 72: 43314. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- ↑ Allan Hopkins, Tax Analyst, Internal Revenue Service (June 13, 2012). "Proposed Collection; Comment Request for Notice 97-19 and Notice 98-34". Federal Register. 77: 35476. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Why it now costs so much to renounce your citizenship". Wall Street Journal. August 24, 2015. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- ↑ "What We Do". United States Department of State. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- ↑ "The existing fee definition covers a projected 5,986 applicants renouncing their U.S. nationality in FY 2015. This rule expands the definition of the fee to cover an additional projected 559 applicants who will relinquish their nationality in FY 2015. The total volume of applicants paying this fee is projected to be 6,545, if in effect for all of FY 2015." Patrick F. Kennedy, Under Secretary of State for Management, U.S. Department of State (September 8, 2015). "Schedule of Fees for Consular Services, Department of State and Overseas Embassies and Consulates-Passport and Citizenship Services Fee Changes". Federal Register. 80: 53704. Retrieved March 21, 2016.