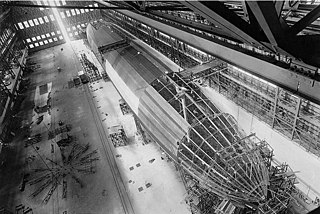

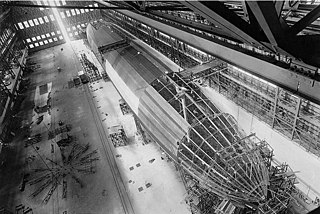

USS Akron (ZRS-4) was a helium-filled rigid airship of the U.S. Navy, the lead ship of her class, which operated between September 1931 and April 1933. It was the world's first purpose-built flying aircraft carrier, carrying F9C Sparrowhawk fighter planes, which could be launched and recovered while it was in flight. With an overall length of 785 ft (239 m), Akron and her sister ship Macon were among the largest flying objects ever built. Although LZ 129 Hindenburg and LZ 130 Graf Zeppelin II were some 18 ft (5.5 m) longer and slightly more voluminous, the two German airships were filled with hydrogen, and so the two US Navy craft still hold the world record for the largest helium-filled airships.

USS Shenandoah was the first of four United States Navy rigid airships. It was constructed during 1922–1923 at Lakehurst Naval Air Station, and first flew in September 1923. It developed the U.S. Navy's experience with rigid airships and made the first crossing of North America by airship. On the 57th flight, Shenandoah was destroyed in a squall line over Ohio in September 1925.

USS Los Angeles was a rigid airship, designated ZR-3, which was built in 1923–1924 by the Zeppelin company in Friedrichshafen, Germany, as war reparations. She was delivered to the United States Navy in October 1924 and after being used mainly for experimental work, particularly in the development of the American parasite fighter program, was decommissioned in 1932.

LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin was a German passenger-carrying hydrogen-filled rigid airship that flew from 1928 to 1937. It offered the first commercial transatlantic passenger flight service. The ship was named after the German airship pioneer Ferdinand von Zeppelin, a count in the German nobility. It was conceived and operated by Hugo Eckener, the chairman of Luftschiffbau Zeppelin.

USS Macon (ZRS-5) was a rigid airship built and operated by the United States Navy for scouting and served as a "flying aircraft carrier", carrying up to five single-seat Curtiss F9C Sparrowhawk parasite biplanes for scouting or two-seat Fleet N2Y-1s for training. In service for less than two years, the Macon was damaged in a storm and lost off California's Big Sur coast in February 1935, though most of the crew were saved. The wreckage is listed as the USS Macon Airship Remains on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places.

His Majesty's Airship R100 was a privately designed and built British rigid airship made as part of a two-ship competition to develop a commercial airship service for use on British Empire routes as part of the Imperial Airship Scheme. The other airship, the R101, was built by the British Air Ministry, but both airships were funded by the Government.

The Curtiss F9C Sparrowhawk is a light 1930s biplane fighter aircraft that was carried by the United States Navy airships USS Akron and Macon. It is an example of a parasite fighter, a small airplane designed to be deployed from a larger aircraft such as an airship or bomber.

R.36 was a British airship designed during World War I, but not completed until after the war. When she first flew in 1921, it was not in her originally intended role as a patrol aircraft for the Royal Navy, but as an airliner, the first airship to carry a civil registration (G-FAAF).

Lakehurst Maxfield Field, formerly known as Naval Air Engineering Station Lakehurst, is the naval component of Joint Base McGuire–Dix–Lakehurst, a United States Air Force-managed joint base. The airfield is approximately 25 mi east-southeast of Trenton in Manchester Township and Jackson Township in Ocean County, New Jersey, United States. It is primarily the home to Naval Air Warfare Center Aircraft Division Lakehurst, although the airfield supports several other flying and non-flying units as well. Its name is an amalgamation of its location and the last name of Commander Louis H. Maxfield, who lost his life when the R-38/USN ZR-2 airship crashed during flight on 24 August 1921 near Hull, England.

The R.80 was a British rigid airship, first flown on 19 July 1920, and was the first fully streamlined airship to be built in Britain. Originally a military project for the British Admiralty, it was completed for commercial passenger-carrying. R.80 proved too small for this role and after being used briefly to train the United States Navy personnel who were to crew the ZR-2 airship, R.80 was retired and eventually scrapped in 1925.

The R31 class of British rigid airships was constructed in the closing months of World War I, and comprised two aircraft, His Majesty's Airship R31 and R32. They were designed by the Royal Corps of Naval Constructors – with assistance from a Herr Müller who had defected to Britain, and previously worked for the Schütte-Lanz airship company – and built by Short Brothers at the Cardington airship sheds. The airship frame was made from spruce plywood laminated into girder sections, weatherproofed with varnish, and also fireproofed. These enclosed 21 gas bags. R31 was the largest British airship to fly before the end of the war, and the class remains the largest mobile wooden structures ever built.

A rigid airship is a type of airship in which the envelope is supported by an internal framework rather than by being kept in shape by the pressure of the lifting gas within the envelope, as in blimps and semi-rigid airships. Rigid airships are often commonly called Zeppelins, though this technically refers only to airships built by the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin company.

Beginning in 1908 and ending in 1937, the U.S. Army established a program to operate airships. With the exceptions of the Italian-built Roma and the Goodyear RS-1, which were both semi-rigid, all Army airships were non-rigid blimps. These airships were used primarily for search and patrol operations in support of coastal fortifications and border patrol. During the 1920s, the Army operated many more blimps than the U.S. Navy. Blimps were selected by the Army because they were not seen as "threats" on the battlefield by opposing forces, unlike airplanes, due to their passive role in combat.

The H class blimp was an observation airship built for the U.S. Navy in the early 1920s. The original "H" Class design of 1919 was for a twin engined airship of approximately 80,000 cubic feet volume. Commander Lewis Maxfield suggested that a small airship which could be used either as a tethered kite balloon, or be towed by a ship until releasing its cable, would be able to scout on its own. The concept was an airship similar to the later Army Motorized Kite Balloons.

RNAS Howden was an airship station near the town of Howden 15 miles (24 km) south-east of York, England.

Major George Herbert "Lucky Breeze" Scott, CBE, AFC, was a British airship pilot and engineer. After serving in the Royal Naval Air Service and Royal Air Force during World War I, Scott went on to command the airship R34 on its return Atlantic crossing in 1919, which marked the first transatlantic flight by an airship and the first east–west transatlantic flight by an aircraft of any kind. Subsequently, he worked at the Royal Airship Works in connection with the Imperial Airship Scheme and took part in a second return Atlantic crossing, this time by the R100, in 1930. He was killed later in the year aboard the R100's near-sister, the R101, when it crashed in northern France during a flight to India.

Unlike later blimp squadrons, which contained several airships, the large rigid airship units consisted of a single airship and, in the case of the USS Akron and USS Macon, a small contingent of fixed-wing aircraft.

The Zeppelin R Class was a type of rigid airship developed by Zeppelin Luftschiffbau in 1916 for use by the Imperial German Navy and the German Army for bombing and naval patrol work. Introduced in July 1916 at a time when British air defences were becoming increasingly capable, several were lost in the first months of operation, leading the Germans to reconsider their technical requirements and eventually to develop airships capable of bombing from a greater height. Most surviving examples were modified to meet these requirements, by reducing weight at the expense of performance. A total of 17 were built.

The Akron-class airships were a class of two rigid airships constructed for the US Navy in the early 1930s. Designed as scouting and reconnaissance platforms, the intention for their use was to act as "eyes for the fleet", extending the range at which the US Navy's Scouting Force could operate to beyond the horizon. This capability was extended further through the use of the airships as airborne aircraft carriers, with each capable of carrying a small squadron of airplanes that could be used both to increase the airship's scouting range, and to provide self-defense for the airship against other airborne threats.