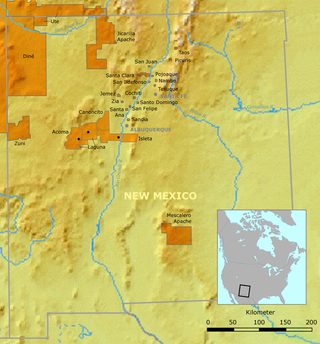

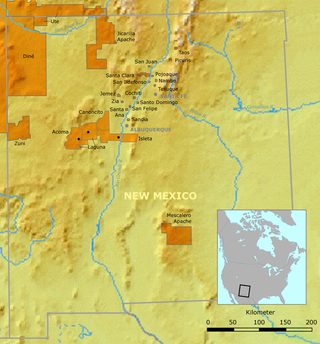

The Puebloans, or Pueblo peoples, are Native Americans in the Southwestern United States who share common agricultural, material, and religious practices. Among the currently inhabited Pueblos, Taos, San Ildefonso, Acoma, Zuni, and Hopi are some of the most commonly known. Pueblo people speak languages from four different language families, and each Pueblo is further divided culturally by kinship systems and agricultural practices, although all cultivate varieties of maize.

In ancient Roman religion, the Manes or Di Manes are chthonic deities sometimes thought to represent souls of deceased loved ones. They were associated with the Lares, Lemures, Genii, and Di Penates as deities (di) that pertained to domestic, local, and personal cult. They belonged broadly to the category of di inferi, "those who dwell below", the undifferentiated collective of divine dead. The Manes were honored during the Parentalia and Feralia in February.

The Dragon King, also known as the Dragon God, is a Chinese water and weather god. He is regarded as the dispenser of rain, commanding over all bodies of water. He is the collective personification of the ancient concept of the lóng in Chinese culture.

Weather modification is the act of intentionally manipulating or altering the weather. The most common form of weather modification is cloud seeding, which increases rain or snow, usually for the purpose of increasing the local water supply. Weather modification can also have the goal of preventing damaging weather, such as hail or hurricanes, from occurring; or of provoking damaging weather against the enemy, as a tactic of military or economic warfare like Operation Popeye, where clouds were seeded to prolong the monsoon in Vietnam. Weather modification in warfare has been banned by the United Nations under the Environmental Modification Convention.

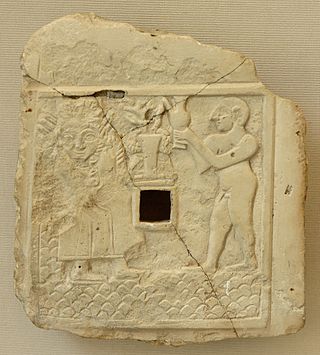

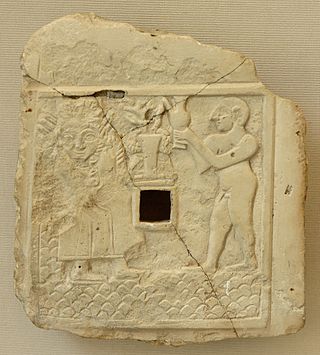

A libation is a ritual pouring of a liquid, or grains such as rice, as an offering to a deity or spirit, or in memory of the dead. It was common in many religions of antiquity and continues to be offered in cultures today.

The Zuni are Native American Pueblo peoples native to the Zuni River valley. The Zuni people today are federally recognized as the Zuni Tribe of the Zuni Reservation, New Mexico, and most live in the Pueblo of Zuni on the Zuni River, a tributary of the Little Colorado River, in western New Mexico, United States. The Pueblo of Zuni is 55 km (34 mi) south of Gallup, New Mexico. The Zuni tribe lived in multi level adobe houses. In addition to the reservation, the tribe owns trust lands in Catron County, New Mexico, and Apache County, Arizona. The Zuni call their homeland Halona Idiwan’a or Middle Place. The word Zuni is believed to derive from the Western Keres language (Acoma) word sɨ̂‧ni, or a cognate thereof.

Caloian (also Calian(i), Caloiță, Scaloian, Gherman, or Iene) was a rainmaking and fertility rite in Romania, similar in some ways to Dodola. Its namesake is a clay effigy, whose sculpting, funeral, exhumation, and eventual destruction are centerpieces of the display. The source of this ritual, as is the case with those of many other local popular beliefs and practices, precedes the introduction of Christianity, although it came in time to be associated with Orthodox Easter or with the Feast of the Ascension. In some variants it was performed on a precisely calculated day two to three weeks after Easter, though local communities could also revive it at other times of the year, specifically during drought. The figurine was generally made from clay and most often by girls, though sometimes also by boys or married women; the ceremony itself would draw in the whole village community as spectators, and, in isolated cases, also had active participation from the Romanian Orthodox clergy. The mimicry of Christian funerals was widespread, but absent from the more established forms of the ritual.

Cloud seeding is a type of weather modification that aims to change the amount or type of precipitation that falls from clouds by dispersing substances into the air that serve as cloud condensation or ice nuclei, which alter the microphysical processes within the cloud. Its effectiveness is debated; some studies have suggested that it is "difficult to show clearly that cloud seeding has a very large effect." The usual objective is to increase precipitation, either for its own sake or to prevent precipitation from occurring in days afterward.

Dodola and Perperuna, are ancient Slavic rainmaking pagan customs practiced until the 20th century. The tradition is found in South Slavic countries, as well as in near Albania, Greece, Hungary, Moldova and Romania.

Rainmaking, also known as artificial precipitation, artificial rainfall and pluviculture, is the act of attempting to artificially induce or increase precipitation, usually to stave off drought or the wider global warming. According to the clouds' different physical properties, this can be done using airplanes or rockets to sow to the clouds with catalysts such as dry ice, silver iodide and salt powder, to make clouds rain or increase precipitation, to remove or mitigate farmland drought, to increase reservoir irrigation water or water supply capacity, to increase water levels for hydropower generation, or even to solve the global warming problem.

The traditional Maya or Mayan religion of the extant Maya peoples of Guatemala, Belize, western Honduras, and the Tabasco, Chiapas, Quintana Roo, Campeche and Yucatán states of Mexico is part of the wider frame of Mesoamerican religion. As is the case with many other contemporary Mesoamerican religions, it results from centuries of symbiosis with Roman Catholicism. When its pre-Hispanic antecedents are taken into account, however, traditional Maya religion has already existed for more than two and a half millennia as a recognizably distinct phenomenon. Before the advent of Christianity, it was spread over many indigenous kingdoms, all with their own local traditions. Today, it coexists and interacts with pan-Mayan syncretism, the 're-invention of tradition' by the Pan-Maya movement, and Christianity in its various denominations.

The Lapis Niger is an ancient shrine in the Roman Forum. Together with the associated Vulcanal it constitutes the only surviving remnants of the old Comitium, an early assembly area that preceded the Forum and is thought to derive from an archaic cult site of the 7th or 8th century BC.

Maya medicine concerns health and medicine among the ancient Maya civilization. It was a complex blend of mind, body, religion, ritual and science. Important to all, medicine was practiced only by a select few, who generally inherited their positions and received extensive education. These shamans acted as a medium between the physical world and spirit world. They practiced sorcery for the purpose of healing, foresight, and control over natural events. Since medicine was so closely related to religion, it was essential that Maya medicine men had vast medical knowledge and skill.

Zennyo Ryūō is a rain-god dragon in Japanese mythology. According to Japanese Buddhist tradition, the priest Kūkai made Zennyo Ryūō appear in 824 AD during a famous rainmaking contest at the Kyoto Imperial Palace.

Kuksu was a religion in Northern California practiced by members within several Indigenous peoples of California before and during contact with the arriving European settlers. The religious belief system was held by several tribes in Central California and Northern California, from the Sacramento Valley west to the Pacific Ocean.

Ecstatic dance is a form of dance in which the dancers, sometimes without the need to follow specific steps, release themselves to the rhythm and move freely as the music takes them, leading to trance and a feeling of ecstasy. The effects of ecstatic dance begin with ecstasy itself, which may be experienced in differing degrees. Dancers are described as feeling connected to others, and to their own emotions. The dance serves as a form of meditation, helping people to cope with stress and to attain serenity.

A lapis manalis was either of two sacred stones used in the Roman religion. One covered a gate to Hades, abode of the dead; Sextus Pompeius Festus called it ostium Orci, "the gate of Orcus". The other was used to make rain; this one may have no direct relationship with the Manes, but is instead derived from the verb manare, "to flow".

The numerous epithets of Jupiter indicate the importance and variety of the god's functions in ancient Roman religion.

Wu is a Chinese term translating to "shaman" or "sorcerer", originally the practitioners of Chinese shamanism or "Wuism".

A snow dance is a ritual that is performed with the hopes of bringing snow in the winter months. This ritual is often performed with the goal of avoiding school or work the next day. Specific snow dance rituals vary from person to person, but commonly include sleeping with silverware under one's pillow, flushing ice cubes down a toilet, or wearing pajamas inside out and backwards. Snow dancing is often performed outside in sunny or rainy conditions as the participating dancer would want it to snow that day or week, rather than be rainy or sunny. Considered by many to be an urban legend, the Snow Dance is often referred to in jest.