Édith Piaf was a French singer noted as France's national chanteuse and one of the country's most widely known international stars.

Ebez also rendered Abez, was a town in the allotment of the tribe of Issachar, at the north of the Jezreel Valley, or plain of Esdraelon. F. R. and C. R. Conder (1879), believed that it was probably the ruins of el-Beida, but William Robertson Smith (1899) expressed doubt about this identification. According to the 1915 International Standard Bible Encyclopedia (1915), the location is not known. It is mentioned only in Joshua 19:20, where various manuscripts of the Septuagint render it as Rebes, Aeme, or Aemis. It is mentioned on the façade of the Mortuary Temple of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu as Apijaa.

Medinet Habu is an archaeological locality situated near the foot of the Theban Hills on the West Bank of the River Nile opposite the modern city of Luxor, Egypt. Although other structures are located within the area, the location is today associated almost exclusively with the Mortuary Temple of Ramesses III.

The Temple of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu was an important New Kingdom period temple structure in the West Bank of Luxor in Egypt. Aside from its size and architectural and artistic importance, the mortuary temple is probably best known as the source of inscribed reliefs depicting the advent and defeat of the Sea Peoples during the reign of Ramesses III.

Georges Émile Jules Daressy was a French Egyptologist.

Claude-Adrien Nonnotte was a French Jesuit controversialist, best known for his writings against Voltaire.

Louis Gaston Adrien de Ségur was a French bishop and charitable pioneer.

Denis Dodart was a French physician, naturalist, and botanist who was born in 1634 in Paris and died on November 5, 1707 in the same city.

Michel de Marolles, known as the abbé de Marolles, was a French churchman and translator, known for his collection of old master prints. He became a monk in 1610 and later was abbot of Villeloin (1626–1674). He was the author of many translations of Latin poets and was part of many salons, notably that of Madeleine de Scudéry. He is best known for having collected 123,000 prints - this acquisition is considered the foundation of the cabinet of prints in the royal library, though it was only constituted as a department in 1720.

The Old University of Leuven is the name historians give to the university, or studium generale, founded in Leuven, Brabant, in 1425. The university was closed in 1797, a week after the cession to the French Republic of the Austrian Netherlands and the principality of Liège by the Treaty of Campo Formio.

Barthélemy Mercier de Saint-Léger was a French abbot and librarian.

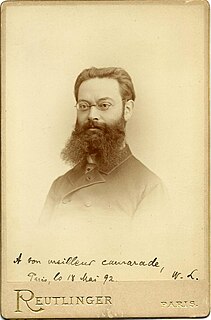

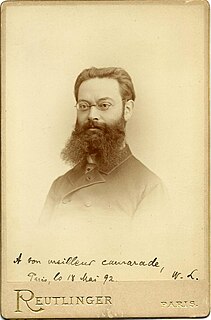

Wolff Wilhelm Lowenthal was a silesian-born, naturalized French Doctor of Medicine.

The memorial temple of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu contains a minor list of pharaohs of the New Kingdom of Egypt. The inscriptions closely resemble the Ramesseum king list, which is a similar scene of Ramesses II, which was used as a template for the scenes here.

Les Feuilles d'Automne is a collection of poems written by Victor Hugo, and published in 1831. It contains a multitude of poems, six of which are especially known as Soleils Couchants.

Cyperus dives is a plant in the genus Cyperus of the sedge family, Cyperaceae, which is found from south-west Syria to Africa, and from Pakistan to Vietnam.

Gilbert Garcin was a French photographer.

The Yehawmilk stele, de Clercq stele, or Byblos stele, also known as KAI 10 and CIS I 1, is a Phoenician inscription from c.450 BC found in Byblos at the end of Ernest Renan's Mission de Phénicie. Yehawmilk, king of Byblos, dedicated the stele to the city’s protective goddess Ba'alat Gebal.

The Neirab steles are two 8th-century BC steles with Aramaic inscriptions found in 1891 in Al-Nayrab near Aleppo, Syria. They are currently in the Louvre. They were discovered in 1891 and acquired by Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau for the Louvre on behalf of the Commission of the Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum. The steles are made of black basalt, and the inscriptions note that they were funerary steles.

The Abydos graffiti is Phoenician and Aramaic graffiti found on the walls of the Temple of Seti I at Abydos, Egypt. The inscriptions are known as KAI 49, CIS I 99-110 and RES 1302ff.

Gabriel Kitenge was a Congolese and Katangese politician.