| Part of a series on |

| Reading |

|---|

|

A reading disability is a condition in which a person displays difficulty reading. Examples of reading disabilities include developmental dyslexia and alexia (acquired dyslexia).

| Part of a series on |

| Reading |

|---|

|

A reading disability is a condition in which a person displays difficulty reading. Examples of reading disabilities include developmental dyslexia and alexia (acquired dyslexia).

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke defines reading disability or dyslexia as follows: "Dyslexia is a brain-based type of learning disability that specifically impairs a person's ability to read. These individuals typically read at levels significantly lower than expected despite having normal intelligence. Although the disorder varies from person to person, common characteristics among people with dyslexia are difficulty with spelling, phonological processing (the manipulation of sounds), and rapid visual-verbal responding. In adults, dyslexia usually occurs after a brain injury or in the context of dementia. It can also be inherited in some families, and recent studies have identified a number of genes that may predispose an individual to developing dyslexia." [1] The NINDS definition is not in keeping with the bulk of scientific studies that conclude that there is no evidence to suggest that dyslexia and intelligence are related. [2] Definition is more in keeping with modern research and debunked discrepancy model of dyslexia diagnosis: [3]

Dyslexia is a learning disability that manifests itself as a difficulty with word decoding and reading fluency. Comprehension may be affected as a result of difficulties with decoding, but is not a primary feature of dyslexia. It is separate and distinct from reading difficulties resulting from other causes, such as a non-neurological deficiency with vision or hearing, or from poor or inadequate reading instruction. [4] It is estimated that dyslexia affects between 5–17% of the population. [5] [6] [7] Dyslexia has been proposed to have three cognitive subtypes (auditory, visual and attentional), although individual cases of dyslexia are better explained by the underlying neuropsychological deficits and co-occurring learning disabilities (e.g. attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, math disability, etc.). [6] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] Although not an intellectual disability, it is considered both a learning disability [13] [14] and a reading disability. [13] [15] Dyslexia and IQ are not interrelated, since reading and cognition develop independently in individuals who have dyslexia. [16] "Nerve problems can cause damage to the control of eye muscles which can also cause diplopia." [17]

Students with dyslexia require a tailored approach in writing courses due to the impact of their neurological condition on their reading, writing, and spelling abilities. [18] [19] This approach is intended to aid their learning and maximize their potential. The incorporation of inclusive writing practices within the curriculum allows students with dyslexia to achieve a parallel education as their peers who do not have dyslexia or other reading disabilities. [18] [19] These practices provide effective strategies for writing courses to cater to the unique needs of students with dyslexia. [18] [19] For instance, John Corrigan, a graduate student with dyslexia, indicates that "the best method is one-on-one [assistance]" [19] from professors or teachers in order to elevate the students' comprehension and strengthen their abilities in the classroom. Additionally, Corrigan states that the incorporation of audible text options are beneficial to students who are developing their writing skills. [19] Corrigan's claim also implies that recorded lectures or self-recording class materials would serve a student with dyslexia. [19] Sioned Exley's study concluded that an alternative approach to implementing inclusive writing practices is through kinesthetic teaching. [18] [20] [21] Exley argues that a student with dyslexia may understand material through visual learning opposed to auditory engagement, as auditory processing tends to be a compromised ability in many people with dyslexia. [18] [20] [21] [22] Implementing inclusive writing practices in the education system, specifically targeting youth education, will pave a route for increased higher-level educational opportunities for individuals with dyslexia in their adult years. [23]

Hyperlexic children are characterized by word-reading ability well above what would be expected given their ages and IQs. [24] Hyperlexia can be viewed as a superability in which word recognition ability goes far above expected levels of skill. [25] However, in spite of few problems with decoding, comprehension is poor. Some hyperlexics also have trouble understanding speech. [25] Most children with hyperlexia lie on the autism spectrum. [25] Between 5–10% of autistic children have been estimated to be hyperlexic. [26]

Remediation includes both appropriate remedial instruction and classroom accommodations.

Dyslexia, previously known as word blindness, is a learning disability that affects either reading or writing. Different people are affected to different degrees. Problems may include difficulties in spelling words, reading quickly, writing words, "sounding out" words in the head, pronouncing words when reading aloud and understanding what one reads. Often these difficulties are first noticed at school. The difficulties are involuntary, and people with this disorder have a normal desire to learn. People with dyslexia have higher rates of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), developmental language disorders, and difficulties with numbers.

Hyperlexia is a syndrome characterized by a child's precocious ability to read. It was initially identified by Norman E. Silberberg and Margaret C. Silberberg (1967), who defined it as the precocious ability to read words without prior training in learning to read, typically before the age of five. They indicated that children with hyperlexia have a significantly higher word-decoding ability than their reading comprehension levels. Children with hyperlexia also present with an intense fascination for written material at a very early age.

Dyscalculia is a learning disability resulting in difficulty learning or comprehending arithmetic, such as difficulty in understanding numbers, learning how to manipulate numbers, performing mathematical calculations, and learning facts in mathematics. It is sometimes colloquially referred to as "math dyslexia", though this analogy can be misleading as they are distinct syndromes.

Mixed receptive-expressive language disorder is a communication disorder in which both the receptive and expressive areas of communication may be affected in any degree, from mild to severe. Children with this disorder have difficulty understanding words and sentences. This impairment is classified by deficiencies in expressive and receptive language development that is not attributed to sensory deficits, nonverbal intellectual deficits, a neurological condition, environmental deprivation or psychiatric impairments. Research illustrates that 2% to 4% of five year olds have mixed receptive-expressive language disorder. This distinction is made when children have issues in expressive language skills, the production of language, and when children also have issues in receptive language skills, the understanding of language. Those with mixed receptive-language disorder have a normal left-right anatomical asymmetry of the planum temporale and parietale. This is attributed to a reduced left hemisphere functional specialization for language. Taken from a measure of cerebral blood flow (SPECT) in phonemic discrimination tasks, children with mixed receptive-expressive language disorder do not exhibit the expected predominant left hemisphere activation. Mixed receptive-expressive language disorder is also known as receptive-expressive language impairment (RELI) or receptive language disorder.

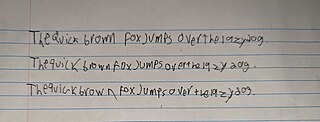

Dysgraphia is a neurological disorder and learning disability that concerns impairments in written expression, which affects the ability to write, primarily handwriting, but also coherence. It is a specific learning disability (SLD) as well as a transcription disability, meaning that it is a writing disorder associated with impaired handwriting, orthographic coding and finger sequencing. It often overlaps with other learning disabilities and neurodevelopmental disorders such as speech impairment, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or developmental coordination disorder (DCD).

Reading for special needs has become an area of interest as the understanding of reading has improved. Teaching children with special needs how to read was not historically pursued due to perspectives of a Reading Readiness model. This model assumes that a reader must learn to read in a hierarchical manner such that one skill must be mastered before learning the next skill. This approach often led to teaching sub-skills of reading in a decontextualized manner. This style of teaching made it difficult for children to master these early skills, and as a result, did not advance to more advanced literacy instruction and often continued to receive age-inappropriate instruction.

The Geschwind–Galaburda hypothesis is a neurological theory proposed by Norman Geschwind and Albert Galaburda in 1987. The hypothesis posits there are sex differences in cognitive abilities by relating them to lateralisation of brain function. The maturation rates of cerebral hemispheres differ and are mediated by circuiting testosterone levels, which are substantially influenced during the foetal and post-puberty development stages.

Developmental coordination disorder (DCD), also known as developmental motor coordination disorder, developmental dyspraxia or simply dyspraxia, is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by impaired coordination of physical movements as a result of brain messages not being accurately transmitted to the body. Deficits in fine or gross motor skills movements interfere with activities of daily living. It is often described as disorder in skill acquisition, where the learning and execution of coordinated motor skills is substantially below that expected given the individual's chronological age. Difficulties may present as clumsiness, slowness and inaccuracy of performance of motor skills. It is often accompanied by difficulty with organisation and/or problems with attention, working memory and time management.

Learning disability, learning disorder, or learning difficulty is a condition in the brain that causes difficulties comprehending or processing information and can be caused by several different factors. Given the "difficulty learning in a typical manner", this does not exclude the ability to learn in a different manner. Therefore, some people can be more accurately described as having a "learning difference", thus avoiding any misconception of being disabled with a possible lack of an ability to learn and possible negative stereotyping. In the United Kingdom, the term "learning disability" generally refers to an intellectual disability, while conditions such as dyslexia and dyspraxia are usually referred to as "learning difficulties".

Management of dyslexia depends on a multitude of variables; there is no one specific strategy or set of strategies that will work for all who have dyslexia.

The Center for Research, Evaluation and Awareness of Dyslexia is a university-based program at Pittsburg State University in Pittsburg, Kansas, United States. It was established in 1996 to develop strategies for the prevention and remediation of reading disabilities, search for strategies that will lead to the improvement of remedial processes, provide educators and parents with current and appropriate knowledge regarding reading/learning disabilities, provide interdisciplinary evaluations of readers of all ages, promote the concerns relevant to reading disabilities and educate the general public regarding issues pertaining to reading/learning disabilities.

Language-based learning disabilities or LBLD are "heterogeneous" neurological differences that can affect skills such as listening, reasoning, speaking, reading, writing, and math calculations. It is also associated with movement, coordination, and direct attention. LBLD is not usually identified until the child reaches school age. Most people with this disability find it hard to communicate, to express ideas efficiently and what they say may be ambiguous and hard to understand It is a neurological difference. It is often hereditary, and is frequently associated to specific language problems.

The history of dyslexia research spans from the late 1800s to the present.

Dyslexia is a reading disorder wherein an individual experiences trouble with reading. Individuals with dyslexia have normal levels of intelligence but can exhibit difficulties with spelling, reading fluency, pronunciation, "sounding out" words, writing out words, and reading comprehension. The neurological nature and underlying causes of dyslexia are an active area of research. However, some experts believe that the distinction of dyslexia as a separate reading disorder and therefore recognized disability is a topic of some controversy.

Dyslexia is a complex, lifelong disorder involving difficulty in learning to read or interpret words, letters and other symbols. Dyslexia does not affect general intelligence, but is often co-diagnosed with ADHD. There are at least three sub-types of dyslexia that have been recognized by researchers: orthographic, or surface dyslexia, phonological dyslexia and mixed dyslexia where individuals exhibit symptoms of both orthographic and phonological dyslexia. Studies have shown that dyslexia is genetic and can be passed down through families, but it is important to note that, although a genetic disorder, there is no specific locus in the brain for reading and writing. The human brain does have language centers, but written language is a cultural artifact, and a very complex one requiring brain regions designed to recognize and interpret written symbols as representations of language in rapid synchronization. The complexity of the system and the lack of genetic predisposition for it is one possible explanation for the difficulty in acquiring and understanding written language.

Dyslexia is a disorder characterized by problems with the visual notation of speech, which in most languages of European origin are problems with alphabet writing systems which have a phonetic construction. Examples of these issues can be problems speaking in full sentences, problems correctly articulating Rs and Ls as well as Ms and Ns, mixing up sounds in multi-syllabic words, problems of immature speech such as "wed and gween" instead of "red and green".

Educational neuroscience is an emerging scientific field that brings together researchers in cognitive neuroscience, developmental cognitive neuroscience, educational psychology, educational technology, education theory and other related disciplines to explore the interactions between biological processes and education. Researchers in educational neuroscience investigate the neural mechanisms of reading, numerical cognition, attention and their attendant difficulties including dyslexia, dyscalculia and ADHD as they relate to education. Researchers in this area may link basic findings in cognitive neuroscience with educational technology to help in curriculum implementation for mathematics education and reading education. The aim of educational neuroscience is to generate basic and applied research that will provide a new transdisciplinary account of learning and teaching, which is capable of informing education. A major goal of educational neuroscience is to bridge the gap between the two fields through a direct dialogue between researchers and educators, avoiding the "middlemen of the brain-based learning industry". These middlemen have a vested commercial interest in the selling of "neuromyths" and their supposed remedies.

Phonological dyslexia is a reading disability that is a form of alexia, resulting from brain injury, stroke, or progressive illness and that affects previously acquired reading abilities. The major distinguishing symptom of acquired phonological dyslexia is that a selective impairment of the ability to read pronounceable non-words occurs although the ability to read familiar words is not affected. It has also been found that the ability to read non-words can be improved if the non-words belong to a family of pseudohomophones.

The simple view of reading is that reading is the product of decoding and linguistic comprehension.

Deaf and hard of hearing individuals with additional disabilities are referred to as "Deaf Plus" or "Deaf+". Deaf children with one or more co-occurring disabilities could also be referred to as hearing loss plus additional disabilities or Deafness and Diversity (D.A.D.). About 40–50% of deaf children experience one or more additional disabilities, with learning disabilities, intellectual disabilities, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and visual impairments being the four most concomitant disabilities. Approximately 7–8% of deaf children have a learning disability. Deaf plus individuals utilize various language modalities to best fit their communication needs.