The American Revolutionary War, also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a military conflict that was part of the broader American Revolution, where American Patriot forces organized as the Continental Army and commanded by George Washington defeated the British Army.

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Crown, notably with the loyalists opponents of the American Revolution, and United Empire Loyalists who moved to other colonies in British North America after the revolution.

United Empire Loyalist is an honorific title which was first given by the 1st Lord Dorchester, the Governor of Quebec and Governor General of the Canadas, to American Loyalists who resettled in British North America during or after the American Revolution. At that time, the demonym Canadian or Canadien was used to refer to the indigenous First Nations groups and the descendants of New France settlers inhabiting the Province of Quebec.

Benjamin West, was a British-American artist who painted famous historical scenes such as The Death of Nelson, The Death of General Wolfe, the Treaty of Paris, and Benjamin Franklin Drawing Electricity from the Sky.

The Battle of Kings Mountain was a military engagement between Patriot and Loyalist militias in South Carolina during the Southern Campaign of the American Revolutionary War, resulting in a decisive victory for the Patriots. The battle took place on October 7, 1780, 9 miles (14 km) south of the present-day town of Kings Mountain, North Carolina. In what is now rural Cherokee County, South Carolina, the Patriot militia defeated the Loyalist militia commanded by British Major Patrick Ferguson of the 71st Foot. The battle has been described as "the war's largest all-American fight".

Loyalists were colonists in the Thirteen Colonies who remained loyal to the British Crown during the American Revolutionary War, often referred to as Tories, Royalists or King's Men at the time. They were opposed by the Patriots, who supported the revolution, and called them "persons inimical to the liberties of America."

Patriots, also known as Revolutionaries, Continentals, Rebels, or Whigs, were colonists in the Thirteen Colonies who opposed the Kingdom of Great Britain's control and governance during the colonial era, and supported and helped launch the American Revolution that ultimately established American independence. Patriot politicians led colonial opposition to British policies regarding the American colonies, eventually building support for the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, which was adopted unanimously by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776. After the American Revolutionary War began the year before, in 1775, many Patriots assimilated into the Continental Army, which was commanded by George Washington and which secured victory against the British, leading the British to acknowledge the sovereign independence of the colonies, reflected in the Treaty of Paris, which led to the establishment of the United States in 1783.

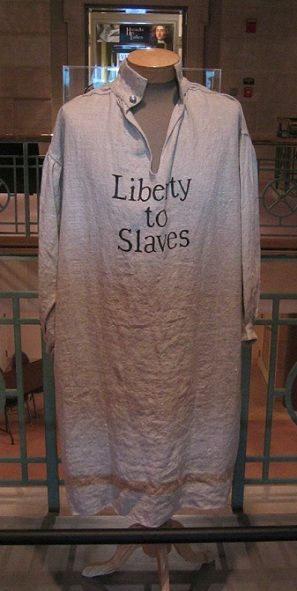

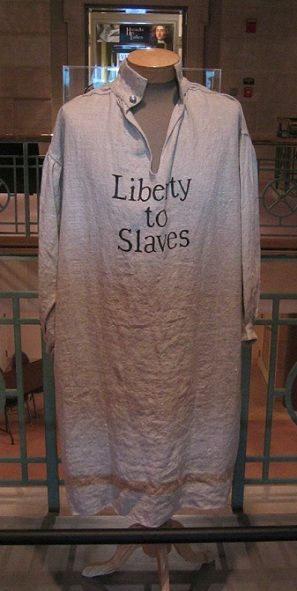

Black Loyalists were African-Americans who sided with the Loyalists during the American Revolutionary War. In particular, the term refers to men who escaped enslavement by Patriot masters and served on the Loyalist side because of the Crown's guarantee of freedom.

Starting with the 1763 Treaty of Paris, New France, of which the colony of Canada was a part, formally became a part of the British Empire. The Royal Proclamation of 1763 enlarged the colony of Canada under the name of the Province of Quebec, which with the Constitutional Act 1791 became known as the Canadas. With the Act of Union 1840, Upper and Lower Canada were joined to become the United Province of Canada.

Edward Winslow was a loyalist officer and New Brunswick judge and official.

The Maryland Loyalists Battalion, also known as the First Battalion of Maryland Loyalists, was a Loyalist infantry unit which served on the side of the Kingdom of Great Britain during the American Revolutionary War. Raised in 1777 by Loyalist officer James Chalmers, the unit, consisting of one battalion, was organizationally part of the British Provincial Corps and saw action at the 1778 Battle of Monmouth and the 1781 Siege of Pensacola. It was disbanded in 1783 in the wake of the Patriot victory in the war.

Sir John Eardley Wilmot PC SL, was an English judge, Chief Justice of the Common Pleas from 1766 to 1771.

Christopher Billopp was a British loyalist during the American Revolution. His command of a Tory detachment during the war earned him the sobriquet, "Tory Colonel". After the American Revolution, he emigrated to New Brunswick, Canada along with other Loyalists and became a politician. He represented Saint John in the 1st New Brunswick Legislative Assembly.

John Eardley Wilmot was a British lawyer and politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1776 to 1796.

During the American Revolution, those who continued to support King George III of Great Britain came to be known as Loyalists. Loyalists are to be contrasted with Patriots, who supported the Revolution. Historians have estimated that during the American Revolution, between 15 and 20 percent of the white population of the colonies, or about 500,000 people, were Loyalists. As the war concluded with Great Britain defeated by the Americans and the French, the most active Loyalists were no longer welcome in the United States, and sought to move elsewhere in the British Empire. The large majority of the Loyalists remained in the United States, however, and enjoyed full citizenship there.

Colonists who supported the British cause in the American Revolution were Loyalists, often called Tories, or, occasionally, Royalists or King's Men. George Washington's winning side in the war called themselves "Patriots", and in this article Americans on the revolutionary side are called Patriots. For a detailed analysis of the psychology and social origins of the Loyalists, see Loyalist.

Thomas Gilbert (1714-1797) was a soldier in King George's War, the French and Indian War and the American Revolution. He was known as the "Leader of the New England Tories". He became a Loyalist, originally from Assonet in Freetown, Massachusetts, he settled a community that was eventually named after him, Gilberts Cove, Nova Scotia.

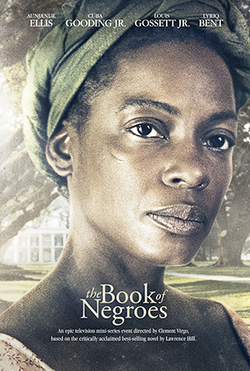

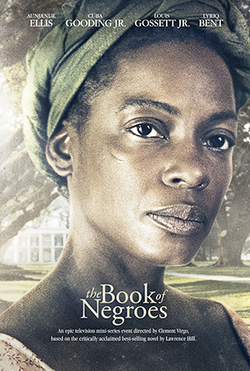

The Book of Negroes is a 2015 television miniseries based on the 2007 novel of the same name by Canadian writer Lawrence Hill. The book was inspired by the British freeing and evacuation of former slaves, known as Black Loyalists, who had left rebel masters during the American Revolutionary War. The British transported some 3,000 Black Loyalists to Nova Scotia for resettlement, documenting their names in what was called the Book of Negroes.

The Province of Nova Scotia was heavily involved in the American Revolutionary War (1776–1783). At that time, Nova Scotia also included present-day New Brunswick until that colony was created in 1784. The Revolution had a significant impact on shaping Nova Scotia, "almost the 14th American Colony". At the beginning, there was ambivalence in Nova Scotia over whether the colony should join the Americans in the war against Britain. Largely as a result of American privateer raids on Nova Scotia villages, as the war continued, the population of Nova Scotia solidified their support for the British. Nova Scotians were also influenced to remain loyal to Britain by the presence of British military units, judicial prosecution by the Nova Scotia Governors and the efforts of Reverend Henry Alline.