Related Research Articles

In trade, barter is a system of exchange in which participants in a transaction directly exchange goods or services for other goods or services without using a medium of exchange, such as money. Economists usually distinguish barter from gift economies in many ways; barter, for example, features immediate reciprocal exchange, not one delayed in time. Barter usually takes place on a bilateral basis, but may be multilateral. In most developed countries, barter usually exists parallel to monetary systems only to a very limited extent. Market actors use barter as a replacement for money as the method of exchange in times of monetary crisis, such as when currency becomes unstable or simply unavailable for conducting commerce.

An incest taboo is any cultural rule or norm that prohibits sexual relations between certain members of the same family, mainly between individuals related by blood. All human cultures have norms that exclude certain close relatives from those considered suitable or permissible sexual or marriage partners, making such relationships taboo. However, different norms exist among cultures as to which blood relations are permissible as sexual partners and which are not. Sexual relations between related persons which are subject to the taboo are called incestuous relationships.

A gift economy or gift culture is a system of exchange where valuables are not sold, but rather given without an explicit agreement for immediate or future rewards. Social norms and customs govern giving a gift in a gift culture; although there is some expectation of reciprocity, gifts are not given in an explicit exchange of goods or services for money, or some other commodity or service. This contrasts with a barter economy or a market economy, where goods and services are primarily explicitly exchanged for value received.

In anthropology, kinship is the web of social relationships that form an important part of the lives of all humans in all societies, although its exact meanings even within this discipline are often debated. Anthropologist Robin Fox says that the study of kinship is the study of what humans do with these basic facts of life – mating, gestation, parenthood, socialization, siblingship etc. Human society is unique, he argues, in that we are "working with the same raw material as exists in the animal world, but [we] can conceptualize and categorize it to serve social ends." These social ends include the socialization of children and the formation of basic economic, political and religious groups.

Economic anthropology is a field that attempts to explain human economic behavior in its widest historic, geographic and cultural scope. It is an amalgamation of economics and anthropology. It is practiced by anthropologists and has a complex relationship with the discipline of economics, of which it is highly critical. Its origins as a sub-field of anthropology began with work by the Polish founder of anthropology Bronislaw Malinowski and the French Marcel Mauss on the nature of reciprocity as an alternative to market exchange. For the most part, studies in economic anthropology focus on exchange.

Marcel Mauss was a French sociologist and anthropologist known as the "father of French ethnology". The nephew of Émile Durkheim, Mauss, in his academic work, crossed the boundaries between sociology and anthropology. Today, he is perhaps better recognised for his influence on the latter discipline, particularly with respect to his analyses of topics such as magic, sacrifice and gift exchange in different cultures around the world. Mauss had a significant influence upon Claude Lévi-Strauss, the founder of structural anthropology. His most famous work is The Gift (1925).

Social exchange theory is a sociological and psychological theory that studies the social behavior in the interaction of two parties that implement a cost-benefit analysis to determine risks and benefits. The theory also involves economic relationships—the cost-benefit analysis occurs when each party has goods that the other parties value. Social exchange theory suggests that these calculations occur in romantic relationships, friendships, professional relationships, and ephemeral relationships as simple as exchanging words with a customer at the cash register. Social exchange theory says that if the costs of the relationship are higher than the rewards, such as if a lot of effort or money were put into a relationship and not reciprocated, then the relationship may be terminated or abandoned.

Kula, also known as the Kula exchange or Kula ring, is a ceremonial exchange system conducted in the Milne Bay Province of Papua New Guinea. The Kula ring was made famous by the father of modern anthropology, Bronisław Malinowski, who used this test case to argue for the universality of rational decision-making and for the cultural nature of the object of their effort. Malinowski's seminal work on the topic, Argonauts of the Western Pacific (1922), directly confronted the question, "Why would men risk life and limb to travel across huge expanses of dangerous ocean to give away what appear to be worthless trinkets?" Malinowski carefully traced the network of exchanges of bracelets and necklaces across the Trobriand Islands, and established that they were part of a system of exchange, and that this exchange system was clearly linked to political authority.

The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies is a 1925 essay by the French sociologist Marcel Mauss that is the foundation of social theories of reciprocity and gift exchange.

Structural anthropology is a school of sociocultural anthropology based on Claude Lévi-Strauss' 1949 idea that immutable deep structures exist in all cultures, and consequently, that all cultural practices have homologous counterparts in other cultures, essentially that all cultures are equatable.

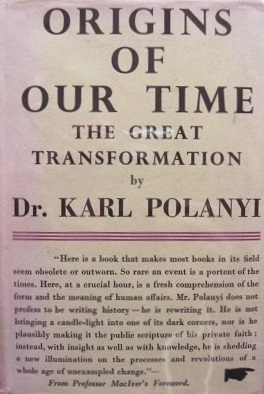

The Great Transformation is a book by Karl Polanyi, a Hungarian political economist. First published in 1944 by Farrar & Rinehart, it deals with the social and political upheavals that took place in England during the rise of the market economy. Polanyi contends that the modern market economy and the modern nation-state should be understood not as discrete elements but as a single human invention, which he calls the "Market Society".

The Moka is a highly ritualized system of exchange in the Mount Hagen area, Papua New Guinea, that has become emblematic of the anthropological concepts of "gift economy" and of "Big man" political system. Moka are reciprocal gifts of pigs through which social status is achieved. Moka refers specifically to the increment in the size of the gift; giving more brings greater prestige to the giver. However, reciprocal gift giving was confused by early anthropologists with profit-seeking, as the lending and borrowing of money at interest.

Alliance theory, also known as the general theory of exchanges, is a structuralist method of studying kinship relations. It finds its origins in Claude Lévi-Strauss's Elementary Structures of Kinship (1949) and is in opposition to the functionalist theory of Radcliffe-Brown. Alliance theory has oriented most anthropological French works until the 1980s; its influences were felt in various fields, including psychoanalysis, philosophy and political philosophy.

In cultural anthropology and sociology, redistribution refers to a system of economic exchange involving the centralized collection of goods from members of a group followed by the redivision of those goods among those members. It is a form of reciprocity. Redistribution differs from simple reciprocity, which is a dyadic back-and-forth exchange between two parties. Redistribution, in contrast, consists of pooling, a system of reciprocities. It is a within group relationship, whereas reciprocity is a between relationship. Pooling establishes a centre, whereas reciprocity inevitably establishes two distinct parties with their own interests. While the most basic form of pooling is that of food within the family, it is also the basis for sustained community efforts under a political leader.

"Gifting remittances" describes a range of scholarly approaches relating remittances to anthropological literature on gift giving. The terms draws on Lisa Cliggett's "gift remitting", but is used to describe a wider body of work. Broadly speaking, remittances are the money, goods, services, and knowledge that migrants send back to their home communities or families. Remittances are typically considered as the economic transactions from migrants to those at home. While remittances are also a subject of international development and policy debate and sociological and economic literature, this article focuses on ties with literature on gifting and reciprocity or gift economy founded largely in the work of Marcel Mauss and Marshall Sahlins. While this entry focuses on remittances of money or goods, remittances also take the form of ideas and knowledge. For more on these, see Peggy Levitt's work on "social remittances" which she defines as "the ideas, behaviors, identities, and social capital that flow from receiving to sending country communities."

Inalienable possessions are things such as land or objects that are symbolically identified with the groups that own them and so cannot be permanently severed from them. Landed estates in the Middle Ages, for example, had to remain intact and even if sold, they could be reclaimed by blood kin. As a legal classification, inalienable possessions date back to Roman times. According to Barbara Mills, "Inalienable possessions are objects made to be kept, have symbolic and economic power that cannot be transferred, and are often used to authenticate the ritual authority of corporate groups".

The exchange of women is an element of alliance theory — the structuralist theory of Claude Lévi-Strauss and other anthropologists who see society as based upon the patriarchal treatment of women as property, being given to other men to cement alliances. Such formal exchange may be seen in the ceremony of the traditional Christian wedding, in which the bride is given to the groom by her father.

Several authors have used the terms organ gifting and "tissue gifting" to describe processes behind organ and tissue transfers that are not captured by more traditional terms such as donation and transplantation. The concept of "gift of life" in the U.S. refers to the fact that "transplantable organs must be given willingly, unselfishly, and anonymously, and any money that is exchanged is to be perceived as solely for operational costs, but never for the organs themselves". "Organ gifting" is proposed to contrast with organ commodification. The maintenance of a spirit of altruism in this context has been interpreted by some as a mechanism through which the economic relations behind organ/tissue production, distribution, and consumption can be disguised. Organ/tissue gifting differs from commodification in the sense that anonymity and social trust are emphasized to reduce the offer and request of monetary compensation. It is reasoned that the implementation of the gift-giving analogy to organ transactions shows greater respect for the diseased body, honors the donor, and transforms the transaction into a morally acceptable and desirable act that is borne out of voluntarism and altruism.

Generalized exchange is a type of social exchange in which a desired outcome that is sought by an individual is not dependent on the resources provided by that individual. It is assumed to be a fundamental social mechanism that stabilizes relations in society by unilateral resource giving in which one's giving is not necessarily reciprocated by the recipient, but by a third party. Thus, in contrast to direct or restricted exchange or reciprocity, in which parties exchange resources with each other, generalized exchange naturally involves more than two parties. Examples of generalized exchange include; matrilateral cross-cousin marriage and helping a stranded driver on a desolate road.

The Traffic in Women: Notes on the "Political Economy" of Sex is an article regarding theories of the oppression of women originally published in 1975 by feminist anthropologist Gayle Rubin. In the article, Rubin argued against the Marxist conceptions of women's oppression—specifically the concept of "patriarchy"—in favor of her own concept of the "sex/gender" system. It was by arguing that women's oppression could not be explained by capitalism alone as well as being an early article to stress the distinction between biological sex and gender that Rubin's work helped to develop women's and gender studies as independent fields. The framework of the article was also important in that it opened up the possibility of researching the change in meaning of this categories over historical time. Rubin used a combination of kinship theories from Lévi-Strauss, psycho-analytic theory from Freud, and critiques of structuralism by Lacan to make her case that it was at moments where women were exchanged that bodies were engendered and became women. Rubin's article has been republished numerous times since its debut in 1975, and it has remained a key piece of feminist anthropological theory and a foundational work in gender studies.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Parry, Jonathan (1986). "The Gift, the Indian Gift and the 'Indian Gift'". Man. 21 (3): 466–8. doi:10.2307/2803096. JSTOR 2803096.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Sahlins, Marshall (1972). Stone Age Economics . Chicago: Aldine-Atherton. ISBN 0-202-01099-6.

- 1 2 Weiner, Annette (1992). Inalienable Possessions: The paradox of keeping-while-giving. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ↑ Malinowski, Bronislaw (1922). Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An Account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagos of Melanesian New Guinea. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- 1 2 Graeber, David (2011). Debt: the first 5,000 years . New York: Melville House. p. 91.

- ↑ Sillitoe, Paul (2006). "Why Spheres of exchange". Ethnology. 45 (1): 16. doi:10.2307/4617561. JSTOR 4617561.

- ↑ Graeber, David (2001). Toward an Anthropological Theory of Value: The false coin of our own dreams . New York: Palgrave. pp. 219–20.

- ↑ Claude Lévi-Strauss, Les structures élémentaires de la parenté, Paris, Mouton, 1967, 2ème édition, p.60

- ↑ Parsons, Laurie (June 2019). "Giving as a total social phenomenon: Towards a human geography of reciprocity". The Geographical Journal. 185 (2): 142–155. doi:10.1111/geoj.12298. ISSN 0016-7398.

- ↑ Guttman, Nurit; Siegal, Gil; Appel, Naama; Bar-On, Gitit (December 2016). "Should Altruism, Solidarity, or Reciprocity be Used as Prosocial Appeals? Contrasting Conceptions of Members of the General Public and Medical Professionals Regarding Promoting Organ Donation: Appeals to Altruism, Solidarity, or Reciprocity". Journal of Communication. 66 (6): 909–936. doi:10.1111/jcom.12267.

- ↑ Venkatesan, Soumhya (2016-01-01). "Giving and Taking without Reciprocity: Conversations in South India and the Anthropology of Ethics". Social Analysis. 60 (3). doi:10.3167/sa.2016.600303. ISSN 0155-977X.