Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian empires, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails, or that it is culturally or historically intertwined with.

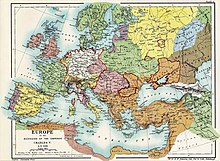

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, aligning with the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD and ended with the fall of Constantinople in 1453 AD before transitioning into the Renaissance and then the Age of Discovery. The Middle Ages is the middle period of the three traditional divisions of Western history: antiquity, medieval, and modern. The medieval period is itself subdivided into the Early, High, and Late Middle Ages. Late medieval scholars at first called these the Dark Ages in contrast to classical antiquity; the accuracy of the term has subsequently been challenged.

A republic, based on the Latin phrase res publica, is a state in which political power rests with the public and their representatives—in contrast to a monarchy.

Early modern Europe, also referred to as the post-medieval period, is the period of European history between the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, roughly the late 15th century to the late 18th century. Historians variously mark the beginning of the early modern period with the invention of moveable type printing in the 1450s, the Fall of Constantinople and end of the Hundred Years’ War in 1453, the end of the Wars of the Roses in 1485, the beginning of the High Renaissance in Italy in the 1490s, the end of the Reconquista and subsequent voyages of Christopher Columbus to the Americas in 1492, or the start of the Protestant Reformation in 1517. The precise dates of its end point also vary and are usually linked with either the start of the French Revolution in 1789 or with the more vaguely defined beginning of the Industrial Revolution in late 18th century England.

In ecclesiology, the Christian Church is what different Christian denominations conceive of as being the true body of Christians or the original institution established by Jesus. "Christian Church" has also been used in academia as a synonym for Christianity, despite the fact that it is composed of multiple churches or denominations, many of which hold a doctrinal claim of being the "one true church", to the exclusion of the others.

Cuius regio, eius religio is a Latin phrase which literally means "whose realm, their religion" – meaning that the religion of the ruler was to dictate the religion of those ruled. This legal principle marked a major development in the collective freedom of religion within Western civilization. Before tolerance of individual religious divergences became accepted, most statesmen and political theorists took it for granted that religious diversity weakened a state – and particularly weakened ecclesiastically-transmitted control and monitoring in a state. The principle of "cuius regio" was a compromise in the conflict between this paradigm of statecraft and the emerging trend toward religious pluralism developing throughout the German-speaking lands of the Holy Roman Empire. It permitted assortative migration of adherents to just two theocracies, Roman Catholic and Lutheran, eliding other confessions.

The crusading movement was a framework of ideologies and institutions that described, regulated, and promoted the Crusades. Members of the Church defined the movement in legal and theological terms based on the concepts of holy war and pilgrimage. Theologically, the movement merged ideas of Old Testament wars that were instigated and assisted by God with New Testament ideas of forming personal relationships with Christ. Crusading was a paradigm that grew from the encouragement of the Gregorian Reform of the 11th century and the movement declined after the Reformation. The ideology continued after the 16th century, but in practical terms dwindled in competition with other forms of religious war and new ideologies.

Church and state in medieval Europe was the relationship between the Catholic Church and the various monarchies and other states in Europe during the Middle Ages.

Mercurino Arborio, marchese di Gattinara, was an Italian statesman and jurist best known as the chancellor of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. He was made cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church for San Giovanni a Porta Latina in 1529.

During the reign of the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great, Christianity began to transition to the dominant religion of the Roman Empire. Historians remain uncertain about Constantine's reasons for favoring Christianity, and theologians and historians have often argued about which form of early Christianity he subscribed to. There is no consensus among scholars as to whether he adopted his mother Helena's Christianity in his youth, or, as claimed by Eusebius of Caesarea, encouraged her to convert to the faith he had adopted.

Greek EastandLatin West are terms used to distinguish between the two parts of the Greco-Roman world and of medieval Christendom, specifically the eastern regions where Greek was the lingua franca and the western parts where Latin filled this role.

The history of Christian thought has included concepts of both inclusivity and exclusivity from its beginnings, that have been understood and applied differently in different ages, and have led to practices of both persecution and toleration. Early Christian thought established Christian identity, defined heresy, separated itself from polytheism and Judaism and developed the theological conviction called supersessionism. In the centuries after Christianity became the official religion of Rome, some scholars say Christianity became a persecuting religion. Others say the change to Christian leadership did not cause a persecution of pagans, and that what little violence occurred was primarily directed at non-orthodox Christians.

The Kingdom of Lithuania was a Lithuanian state, which existed roughly from 1251 to 1263. King Mindaugas was the first and only Lithuanian monarch crowned King of Lithuania with the assent of the Pope. The formation of the Kingdom of Lithuania was a partially successful attempt at unifying all surrounding Baltic tribes, including the Old Prussians, into a single state.

Catholic peace traditions begin with its biblical and classical origins and continue on to the current practice in the twenty-first century. Because of its long history and breadth of geographical and cultural diversity, this Catholic tradition encompasses many strains and influences of both religious and secular peacemaking and many aspects of Christian pacifism, just war and nonviolence.

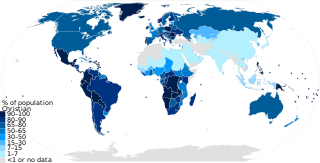

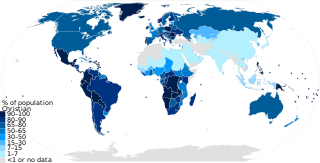

Christianity is the largest religion in Europe. Christianity has been practiced in Europe since the first century, and a number of the Pauline Epistles were addressed to Christians living in Greece, as well as other parts of the Roman Empire.

In the history of Christianity, the first seven ecumenical councils include the following: the First Council of Nicaea in 325, the First Council of Constantinople in 381, the Council of Ephesus in 431, the Council of Chalcedon in 451, the Second Council of Constantinople in 553, the Third Council of Constantinople from 680–681 and finally, the Second Council of Nicaea in 787. All of the seven councils were convened in modern-day Turkey.

The Eastern Roman (Byzantine) imperial church headed by Constantinople continued to assert its universal authority. By the 13th century this assertion was becoming increasingly irrelevant as the Eastern Roman Empire shrank and the Ottoman Turks took over most of what was left of the Byzantine Empire. The other Eastern European churches in communion with Constantinople were not part of its empire and were increasingly acting independently, achieving autocephalous status and only nominally acknowledging Constantinople's standing in the Church hierarchy. In Western Europe the Holy Roman Empire fragmented making it less of an empire as well.

Antemurale Christianitatis was a label used for countries on the frontiers of Christian Europe, defending it from the Ottoman Empire, the Mongol Empire and Orthodox Russia.

Christianity in the Middle Ages covers the history of Christianity from the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The end of the period is variously defined. Depending on the context, events such as the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottoman Empire in 1453, Christopher Columbus's first voyage to the Americas in 1492, or the Protestant Reformation in 1517 are sometimes used.

Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire when Emperor Theodosius I issued the Edict of Thessalonica in 380, which recognized the catholic orthodoxy of Nicene Christians in the Great Church as the Roman Empire's state religion. Most historians refer to the Nicene church associated with emperors in a variety of ways: as the catholic church, the orthodox church, the imperial church, the imperial Roman church, or the Byzantine church, although some of those terms are also used for wider communions extending outside the Roman Empire. The Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodoxy, and the Catholic Church all claim to stand in continuity from the Nicene church to which Theodosius granted recognition.