Right-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that view certain social orders and hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position on the basis of natural law, economics, authority, property or tradition. Hierarchy and inequality may be seen as natural results of traditional social differences or competition in market economies.

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against "the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term developed in the late 19th century and has been applied to various politicians, parties and movements since that time, often as a pejorative. Within political science and other social sciences, several different definitions of populism have been employed, with some scholars proposing that the term be rejected altogether.

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of being radically conservative, ultra-nationalist, and authoritarian, as well as having nativist ideologies and tendencies.

Extremism is "the quality or state of being extreme" or "the advocacy of extreme measures or views". The term is primarily used in a political or religious sense to refer to an ideology that is considered to be far outside the mainstream attitudes of society. It can also be used in an economic context. The term may be used pejoratively by opposing groups, but is also used in academic and journalistic circles in a purely descriptive and non-condemning sense.

The Third Position is a set of neo-fascist political ideologies that were first described in Western Europe following the Second World War. Developed in the context of the Cold War, it developed its name through the claim that it represented a third position between the capitalism of the Western Bloc and the communism of the Eastern Bloc.

Sovereigntism, sovereignism or souverainism is the notion of having control over one's conditions of existence, whether at the level of the self, social group, region, nation or globe. Typically used for describing the acquiring or preserving political independence of a nation or a region, a sovereigntist aims to "take back control" from perceived powerful forces, either against internal subversive minority groups, or from external global governance institutions, federalism and supranational unions. It generally leans instead toward isolationism, and can be associated with certain independence movements, but has also been used to justify violating the independence of other nations.

Right-wing populism, also called national populism and right-wing nationalism, is a political ideology that combines right-wing politics and populist rhetoric and themes. Its rhetoric employs anti-elitist sentiments, opposition to the Establishment, and speaking to or for the "common people". Recurring themes of right-wing populists include neo-nationalism, social conservatism, economic nationalism and fiscal conservatism. Frequently, they aim to defend a national culture, identity, and economy against perceived attacks by outsiders.

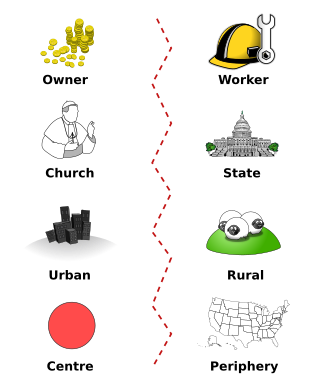

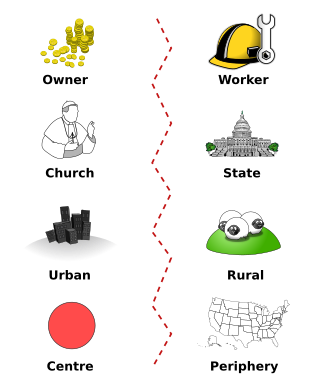

In political science and sociology, a cleavage is a historically determined social or cultural line which divides citizens within a society into groups with differing political interests, resulting in political conflict among these groups. Social or cultural cleavages thus become political cleavages once they get politicized as such. Cleavage theory accordingly argues that political cleavages predominantly determine a country's party system as well as the individual voting behavior of citizens, dividing them into voting blocs. It is distinct from other common political theories on voting behavior in the sense that it focuses on aggregate and structural patterns instead of individual voting behaviors.

The New Canada is a Canadian political literature book written by Reform Party of Canada founder and leader Preston Manning and published by Macmillan Canada. The book explains the personal, religious, and political life of Preston Manning and explains the roots and beliefs of the Reform Party. At the time of its publishing in 1991, Reform had become a popular populist conservative party in Western Canada after the mainstream Progressive Conservative Party of Canada was collapsing in support and in 1991 decided to expand eastward into Ontario and the Maritime provinces. One year later the PC party collapsed in the 1993 federal election, allowing the Reform Party to make political history in Canada, displacing the PCs as the dominant conservative party in Canada. Reform, later renamed the Canadian Alliance, merged with the PC Party in 2003, to form a united right-wing alternative to the governing Liberal Party of Canada, named the Conservative Party of Canada which has dropped many of the populist themes that the Reform Party had.

Cas Mudde is a Dutch political scientist who focuses on political extremism and populism in Europe and the United States. His research includes the areas of political parties, extremism, democracy, civil society and European politics.

Far-left politics, also known as the radical left or extreme left, are politics further to the left on the left–right political spectrum than the standard political left. The term does not have a single, coherent definition. Some scholars consider it to represent the left of social democracy, while others limit it to the left of communist parties. In certain instances, especially in the news media, far left has been associated with some forms of authoritarianism, anarchism, communism, and Marxism, or are characterized as groups that advocate for revolutionary socialism and related communist ideologies, or anti-capitalism and anti-globalization. Far-left terrorism consists of extremist, militant, or insurgent groups that attempt to realize their ideals through political violence rather than using parliamentary processes. Extremist far-left politics have motivated in the last century political violence, radicalization, genocide, terrorism, sabotage and damage to property, the formation of militant organizations, political repression, conspiracism, xenophobia, and nationalism.

In political science and popular discourse, the horseshoe theory asserts that the extreme left and the extreme right, rather than being at opposite and opposing ends of a linear political continuum, closely resemble each other, analogous to the way that the opposite ends of a horseshoe are close together.

Left-wing populism, also called social populism, is a political ideology that combines left-wing politics with populist rhetoric and themes. Its rhetoric often consists of anti-elitism, opposition to the Establishment, and speaking for the "common people". Recurring themes for left-wing populists include economic democracy, social justice, and scepticism of globalization. Socialist theory plays a lesser role than in traditional left-wing ideologies.

In United States politics, the radical right is a political preference that leans towards extreme conservatism, white supremacism, or other right-wing to far-right ideologies in a hierarchical structure paired with conspiratorial rhetoric alongside traditionalist and reactionary aspirations. The term was first used by social scientists in the 1950s regarding small groups such as the John Birch Society in the United States, and since then it has been applied to similar groups worldwide. The term "radical" was applied to the groups because they sought to make fundamental changes within institutions and remove persons and institutions that threatened their values or economic interests from political life.

Alternative for Germany is a right-wing populist political party in Germany. AfD is known for its opposition to the European Union, as well as immigration to Germany. The AfD's ideology is positioned on the radical right, a subset of the far-right, within the family of European political parties.

The social breakdown thesis is a theory that posits that individuals that are socially isolated — living in atomized, socially disintegrated societies — are particularly likely to support right-wing populist parties.

Roger Eatwell is a British academic currently an Emeritus Professor of Politics at the University of Bath.

In political science, the terms radical right and populist right have been used to refer to the range of nationalist, right-wing to far-right parties that have grown in support since the late 1970s in Europe. Populist right groups have shared a number of causes, which typically include opposition to globalisation and immigration, criticism of multiculturalism, and opposition to the European Union.

Populism exists in Europe.

The anti-gender movement is an international movement which opposes what it refers to as "gender ideology", "gender theory" or "genderism". The concepts cover a variety of issues and have no coherent definition. Members of the anti-gender movement include right-wingers and the far right, right-wing populists, conservatives, and Christian fundamentalists. Members of the anti-gender movement oppose some LGBT rights, some reproductive rights, government gender policies, gender equality, gender mainstreaming and gender studies departments. Anti-gender rhetoric has seen increasing circulation in trans-exclusionary radical feminist discourse since 2016.