The Aedui or Haedui were a Gallic tribe dwelling in what is now the region of Burgundy during the Iron Age and the Roman period.

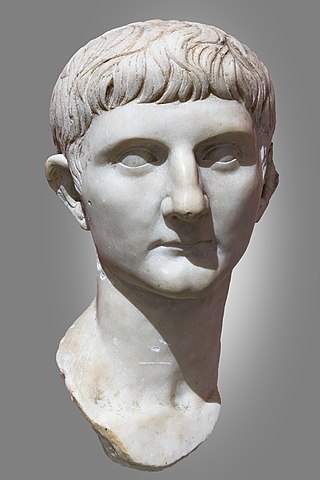

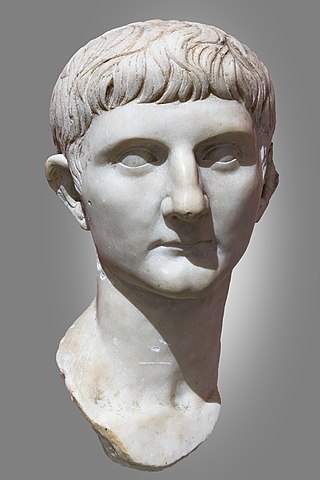

Germanicus Julius Caesar was an ancient Roman general and politician most famously known for his campaigns against Arminius in Germania. The son of Nero Claudius Drusus and Antonia the Younger, Germanicus was born into an influential branch of the patrician gens Claudia. The agnomen Germanicus was added to his full name in 9 BC when it was posthumously awarded to his father in honor of his victories in Germania. In AD 4 he was adopted by his paternal uncle Tiberius, himself the stepson and heir of Germanicus' great-uncle Augustus; ten years later, Tiberius succeeded Augustus as Roman emperor. As a result of his adoption, Germanicus became an official member of the gens Julia, another prominent family, to which he was related on his mother's side. His connection to the Julii Caesares was further consolidated through a marriage between him and Agrippina the Elder, a granddaughter of Augustus. He was also the father of Caligula, the maternal grandfather of Nero, and the older brother of Claudius.

The 20s decade ran from January 1, AD 20, to December 31, AD 29.

AD 21 (XXI) was a common year starting on Wednesday of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Tiberius and Drusus. The denomination AD 21 for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.

The Cherusci were a Germanic tribe that inhabited parts of the plains and forests of northwestern Germania in the area of the Weser River and present-day Hanover during the first centuries BC and AD. Roman sources reported they considered themselves kin with other Irmino tribes and claimed common descent from an ancestor called Mannus. During the early Roman Empire under Augustus, the Cherusci first served as allies of Rome and sent sons of their chieftains to receive Roman education and serve in the Roman army as auxiliaries. The Cherusci leader Arminius led a confederation of tribes in the ambush that destroyed three Roman legions in the Teutoburg Forest in AD 9. He was subsequently kept from further damaging Rome by disputes with the Marcomanni and reprisal attacks led by Germanicus. After rebel Cherusci killed Arminius in AD 21, infighting among the royal family led to the highly Romanized line of his brother Flavus coming to power. Following their defeat by the Chatti around AD 88, the Cherusci do not appear in further accounts of the German tribes, apparently being absorbed into the late classical groups such as the Saxons, Thuringians, Franks, Bavarians, and Allemanni.

The gens Julia was one of the most prominent patrician families in ancient Rome. Members of the gens attained the highest dignities of the state in the earliest times of the Republic. The first of the family to obtain the consulship was Gaius Julius Iulus in 489 BC. The gens is perhaps best known, however, for Gaius Julius Caesar, the dictator and grand uncle of the emperor Augustus, through whom the name was passed to the so-called Julio-Claudian dynasty of the first century AD. The nomen Julius became very common in imperial times, as the descendants of persons enrolled as citizens under the early emperors began to make their mark in history.

Drusus Julius Caesar, also called Drusus the Younger, was the son of Emperor Tiberius, and heir to the Roman Empire following the death of his adoptive brother Germanicus in AD 19.

Drusus Caesar was the grandson by adoption and heir of the Roman emperor Tiberius, alongside his brother Nero. Born into the prominent Julio-Claudian dynasty, Drusus was the son of Tiberius' general and heir, Germanicus.

Publius Cornelius Dolabella was a Roman senator active during the Principate. He was consul in AD 10 with Gaius Junius Silanus as his colleague. Dolabella is known for having reconstructed the Arch of Dolabella in Rome in AD 10, together with his co-consul Junius Silanus. Later, Nero used it for his aqueduct to the Caelian Hill.

The Treveri were a Germanic or Celtic tribe of the Belgae group who inhabited the lower valley of the Moselle in modern day Germany from around 150 BCE, if not earlier, until their displacement by the Franks. Their domain lay within the southern fringes of the Silva Arduenna, a part of the vast Silva Carbonaria, in what are now Luxembourg, southeastern Belgium and western Germany; its centre was the city of Trier, to which the Treveri give their name. Celtic in language, according to Tacitus they claimed Germanic descent. They contained both Gallic and Germanic influences.

Bibracte, a Gallic oppidum, was the capital of the Aedui and one of the most important hillforts in Gaul. It was located near modern Autun in Burgundy, France. The material culture of the Aedui corresponded to the Late Iron Age La Tène culture.

Julius Indus was a nobleman of the Gaulish Treveri tribe. In 21 CE he helped the Romans put down a rebellion of the Treveri and Aedui. Indus had a personal vendetta with one of the leaders in the revolt, Julius Florus. Culminating in a confrontation between the two in the Ardennes forest. During this fight, Indus killed Florus. His regiment may have been involved in the Roman invasion of Britain, and was certainly posted at Corinum (Cirencester) in the mid-to-late 1st century. His daughter, Julia Pacata, married the procurator of Roman Britain, Gaius Julius Alpinus Classicianus, and buried him in London in 65 CE.

Gaius Silius was a Roman senator who achieved successes as a general over German barbarians following the disaster of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest. For this achievement he was appointed consul in AD 13 with Lucius Munatius Plancus as his colleague. However, years later Silius became entangled in machinations of the ambitious Praetorian prefect Sejanus and was forced to commit suicide.

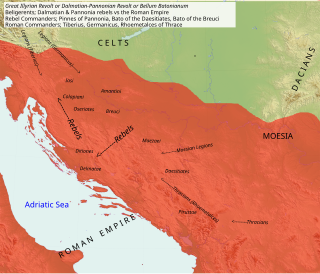

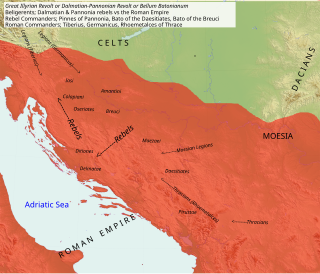

The Bellum Batonianum was a military conflict fought in the Roman province of Illyricum in the 1st century AD, in which an alliance of native peoples of the two regions of Illyricum, Dalmatia and Pannonia, revolted against the Romans. The rebellion began among native peoples who had been recruited as auxiliary troops for the Roman army. They were led by Bato the Daesitiate, a chieftain of the Daesitiatae in the central part of present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina, and were later joined by the Breuci, a tribe in Pannonia led by Bato the Breucian. Many other tribes in Illyria also joined the revolt.

A crupellarius was a type of heavy armored gladiator during the Roman Imperial age, whose origin was Gaul.

Gaius Visellius Varro was a Roman senator, who was active during the reign of Augustus. He was suffect consul in the second half of AD 12, replacing Gaius Fonteius Capito. He was governor of Germania Inferior in the year 21.

Lucius Visellius Varro was a Roman senator, who was active during the reign of Tiberius. He was consul in AD 24 as the colleague of Servius Cornelius Cethegus. He is best known for accusing Gaius Silius of being complicit in Sacrovir's revolt and misappropriating money from the provincial government in Gaul. His prosecution ended with Silius' death.

The gens Silia was a plebeian family at ancient Rome. Members of this gens are mentioned as early as the fifth century BC, but first to hold the consulship was Publius Silius Nerva, in the time of Augustus. The Silii remained prominent until the time of the Severan dynasty, in the early third century.

Julius Sacrovir was a member of the gens Julia. Alongside Julius Florus, a leader of the Treveri, he led the Aedui tribe in Gaul in a revolt against the Romans. After being defeated in battle Sacrovir fled to, and was killed in Augustodunum.