Asperger syndrome (AS), also known as Asperger's syndrome, formerly described a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by significant difficulties in social interaction and nonverbal communication, along with restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, and activities. The syndrome has been merged with other disorders into autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and is no longer considered a stand-alone diagnosis. It was considered milder than other diagnoses that were merged into ASD by relatively unimpaired spoken language and intelligence.

Pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS) is a historic psychiatric diagnosis first defined in 1980 that has since been incorporated into autism spectrum disorder in the DSM-5 (2013).

Diagnoses of autism have become more frequent since the 1980s, which has led to various controversies about both the cause of autism and the nature of the diagnoses themselves. Whether autism has mainly a genetic or developmental cause, and the degree of coincidence between autism and intellectual disability, are all matters of current scientific controversy as well as inquiry. There is also more sociopolitical debate as to whether autism should be considered a disability on its own.

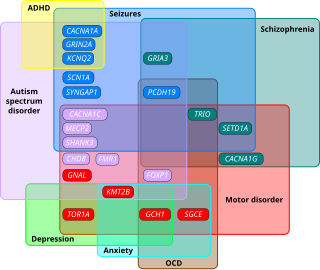

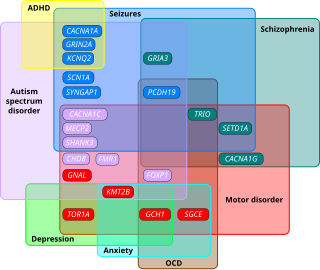

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are neurodevelopmental disorders that begin in early childhood, persist throughout adulthood, and affect three crucial areas of development: communication, social interaction and restricted patterns of behavior. There are many conditions comorbid to autism spectrum disorders such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and epilepsy.

High-functioning autism (HFA) was historically an autism classification where a person exhibits no intellectual disability, but may experience difficulty in communication, emotion recognition, expression, and social interaction.

The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) is a standardized diagnostic test for assessing autism spectrum disorder. The protocol consists of a series of structured and semi-structured tasks that involve social interaction between the examiner and the person under assessment. The examiner observes and identifies aspects of the subject's behavior, assigns these to predetermined categories, and combines these categorized observations to produce quantitative scores for analysis. Research-determined cut-offs identify the potential diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder, allowing a standardized assessment of autistic symptoms.

Autism therapies include a wide variety of therapies that help people with autism, or their families. Such methods of therapy seek to aid autistic people in dealing with difficulties and increase their functional independence.

The epidemiology of autism is the study of the incidence and distribution of autism spectrum disorders (ASD). A 2022 systematic review of global prevalence of autism spectrum disorders found a median prevalence of 1% in children in studies published from 2012 to 2021, with a trend of increasing prevalence over time. However, the study's 1% figure may reflect an underestimate of prevalence in low- and middle-income countries.

The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ) is a questionnaire published in 2001 by Simon Baron-Cohen and his colleagues at the Autism Research Centre in Cambridge, UK. Consisting of fifty questions, it aims to investigate whether adults of average intelligence have symptoms of autism spectrum conditions. More recently, versions of the AQ for children and adolescents have also been published.

Asperger syndrome (AS) was formerly a separate diagnosis under autism spectrum disorder. Under the DSM-5 and ICD-11, patients formerly diagnosable with Asperger syndrome are diagnosable with Autism Spectrum Disorder. The term is considered offensive by some autistic individuals. It was named after Hans Asperger (1906–80), who was an Austrian psychiatrist and pediatrician. An English psychiatrist, Lorna Wing, popularized the term "Asperger's syndrome" in a 1981 publication; the first book in English on Asperger syndrome was written by Uta Frith in 1991 and the condition was subsequently recognized in formal diagnostic manuals later in the 1990s.

Classic autism, also known as childhood autism, autistic disorder, (early) infantile autism, infantile psychosis, Kanner's autism,Kanner's syndrome, or (formerly) just autism, is a neurodevelopmental condition first described by Leo Kanner in 1943. It is characterized by atypical and impaired development in social interaction and communication as well as restricted, repetitive behaviors, activities, and interests. These symptoms first appear in early childhood and persist throughout life.

Several factors complicate the diagnosis of Asperger syndrome (AS), an autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Like other ASD forms, Asperger syndrome is characterized by impairment in social interaction accompanied by restricted and repetitive interests and behavior; it differs from the other ASDs by having no general delay in language or cognitive development. Problems in diagnosis include disagreement among diagnostic criteria, the controversy over the distinction between AS and other ASD forms or even whether AS exists as a separate syndrome, and over- and under-diagnosis for non-technical reasons. As with other ASD forms, early diagnosis is important, and differential diagnosis must consider several other conditions.

Autism, formally called autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or autism spectrum condition (ASC), is a neurodevelopmental disorder marked by deficits in reciprocal social communication and the presence of restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior. Other common signs include difficulty with social interaction, verbal and nonverbal communication, along with perseverative interests, stereotypic body movements, rigid routines, and hyper- or hyporeactivity to sensory input. Autism is clinically regarded as a spectrum disorder, meaning that it can manifest very differently in each person. For example, some are nonspeaking, while others have proficient spoken language. Because of this, there is wide variation in the support needs of people across the autism spectrum.

Diagnosis, treatment, and experiences of autism varies globally. Although the diagnosis of autism is rising in post-industrial nations, diagnosis rates are much lower in developing nations.

The history of autism spans over a century; autism has been subject to varying treatments, being pathologized or being viewed as a beneficial part of human neurodiversity. The understanding of autism has been shaped by cultural, scientific, and societal factors, and its perception and treatment change over time as scientific understanding of autism develops.

The Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT) is a psychological questionnaire that evaluates risk for autism spectrum disorder in children ages 16–30 months. The 20-question test is filled out by the parent, and a follow-up portion is available for children who are classified as medium- to high-risk for autism spectrum disorder. Children who score in the medium to high-risk zone may not necessarily meet criteria for a diagnosis. The checklist is designed so that primary care physicians can interpret it immediately and easily. The M-CHAT has shown fairly good reliability and validity in assessing child autism symptoms in recent studies.

Sex and gender differences in autism exist regarding prevalence, presentation, and diagnosis.

Edward Ross Ritvo was an American psychiatrist known for his research on genetic components of autism. He was a professor emeritus of UCLA's Neuropsychiatric Institute.

The diagnosis of autism is based on a person's reported and directly observed behavior. There are no known biomarkers for autism spectrum conditions that allow for a conclusive diagnosis.