Related Research Articles

Osei Bonsu also known as Osei Tutu Kwame was the Asantehene. He reigned either from 1800 to 1824 or from 1804 to 1824. During his reign as the king, the Ashanti fought the Fante confederation and ended up dominating Gold Coast trade. In Akan, Bonsu means whale, and is symbolic of his achievement of extending the Ashanti Empire to the coast. He died in Kumasi, and was succeeded by Osei Yaw Akoto.

Kwaku Dua Panin was the eighth Asantehene of the Ashanti Empire from 25 August 1834 until his death.

Kusi Obodom was the 3rd Asantehene of the Ashanti Empire from 1750 to 1764. He was elected as the successor to Opoku Ware I as opposed to the nominee suggested by Opoku Ware I. Obodom's reign was inaugurated with a civil war in response to his election until stability ensued by 1751.

Opoku Ware I was the 2nd Asantehene of Oyoko heritage, who ruled the Ashanti Empire. Between 1718 and 1722, Opoku Ware became Asantehene during a period of civil disorder after the death of the 1st Asanthene. From 1720 to 1721, Opoku established his power.

The Ghana Premier League, currently known as the betPawa Premier League for sponsorship reasons, is the top professional association football division of the football league system in Ghana. Officially formed in 1956 to replace a previous league incarnation, the Gold Coast Club Competition, the league is organized by the Ghana Football Association and was ranked as the 11th best league in Africa by the IFFHS from 2001 to 2010, and the league was also ranked 65th in the IFFHS' Best Leagues of the World ranking, in the 1st Decade of the 21st Century (2001–2010). on 4 February 2014. It has been dominated by Asante Kotoko and Hearts of Oak. The bottom 3 teams are relegated at the end of each season and placed in each zone of the Ghanaian Division One League.

Articles related to Ghana include:

The Akyem are an Akan people. The term Akyem is used to describe a group of four states: Asante Akyem, Akyem Abuakwa, Akyem Kotoku and Akyem Bosome. These nations are located primarily in the eastern region in south Ghana. The term is also used to describe the general area where the Akyem ethnic group clusters. The Akyem ethnic group make up between 3-4 percent of Ghana's population depending on how one defines the group and are very prominent in all aspects of Ghanaian life. The Akyem are a matrilineal people. The history of this ethnic group is that of brave warriors who managed to create a thriving often influential and relatively independent state within modern-day Ghana. When one talks of Ghanaian history, there is often mention of The Big Six. These were six individuals who played a big role in the independence of Ghana. Of the big six, people of Akyem descent made up the majority.

Osei Kwadwo was the 4th Asantehene of the Ashanti Empire who reigned from 1764 to 1777. He was succeeded by Osei Kwame Panyin.

Akwamu was a state set up by the Akwamu people in present-day Ghana. After migrating from Bono state, the Akan founders of Akwamu settled in Twifo-Heman. The Akwamu led an expansionist empire in the 17th and 18th centuries. At the peak of their empire, Akwamu extended 400 kilometres (250 mi) along the coast from Ouidah, Benin in the East to Winneba, Ghana in the West.

The Asante Empire, today commonly called the Ashanti Empire, was an Akan state that lasted from 1701 to 1901, in what is now modern-day Ghana. It expanded from the Ashanti Region to include most of Ghana as well as parts of Ivory Coast and Togo. Due to the empire's military prowess, wealth, architecture, sophisticated hierarchy and culture, the Ashanti Empire has been extensively studied and has more historic records written by European, primarily British, authors than any other indigenous culture of Sub-Saharan Africa.

Professor Emeritus Ivor G. Wilks was a noted British Africanist and historian, specializing in Ghana. Considered one of the founders of modern African historiography, he was an authority on the Ashanti Empire in Ghana and the Welsh working-class movement in the 19th century. At the time of his death, he was Professor Emeritus of History at Northwestern University in Illinois, USA.

The Asante, also known as Ashanti are part of the Akan ethnic group and are native to the Ashanti Region of modern-day Ghana. Asantes are the last group to emerge out of the various Akan civilisations. Twi is spoken by over nine million Asante people as a first or second language.

Kwadwo Akyampon was an agent of Osei Bonsu who acted as representative to both the Fante government at Elmina and the Dutch colonial officials at that location. In this position he essential acted as the Ashanti Empire governor over El Mina. In 1828 Akyampon commanded a contingent of forces in the defense of Elmina against attacks by Fante, Denkyera and Wasa forces.

Akyaawa Yikwan was a royalty from the Asante Kingdom who served as chief negotiator of the 1831 Anglo-Asante peace treaty.

The Ashanti Empire was an Akan empire and kingdom from 1701 to 1957, in modern-day Ghana. The military of the Ashanti Empire first came into formation around the 17th century AD in response to subjugation by the Denkyira Kingdom. It served as the main armed forces of the empire until it was dissolved when the Ashanti became a British crown colony in 1901. In 1701, King Osei Kofi Tutu I won Ashanti independence from Denkyira at the Battle of Feyiase and carried out an expansionist policy.

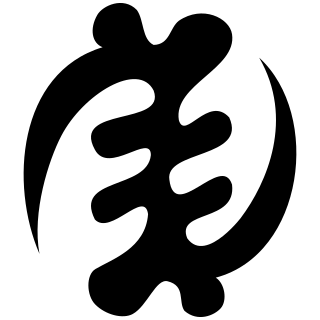

The political organization of the historical Ashanti Empire was characterized by stools which denoted "offices" that were associated with a particular authority. The Golden Stool was the most powerful of all, because it was the office of the King of the Ashanti Empire. Scholars such as Jan Vansina have described the governance of the Ashanti Empire as a federation where state affairs were regulated by a council of elders headed by the king, who was simply primus inter pares.

The Ashanti Empire was governed by an elected monarch with its political power centralised. The entire government was a federation. By the 19th century, the Empire had a total population of 3 million. The Ashanti society was matrilineal as most families were extended and were headed by a male elder who was assisted by a female elder. Asante twi was the most common and official language. At its peak from the 18th–19th centuries, the Empire extended from the Komoé River in the West to the Togo Mountains in the East.

Ghana was initially referred to as the Gold Coast. After attaining independence, the country's first sovereign government named the state after the Ghana Empire in modern Mauritania and Mali. Gold Coast was initially inhabited by different states, empires and ethnic groups before its colonization by the British Empire. The earliest known physical remains of the earliest man in Ghana were first discovered by archaeologists in a rock shelter at Kintampo during the 1960s. The remains were dated to be 5000 years old and it marked the period of transition to sedentism in Ghana. Early Ghanaians used Acheulean stone tools as hunter gatherers during the Early stone age. These stone tools evolved throughout the Middle and Late Stone Ages, during which some early Ghanaians inhabited caves.

The Economy of the Ashanti Empire was largely a pre-industrial and agrarian economy. The Ashanti established different procedures for mobilizing state revenue and utilizing public finance. Ashanti trade extended upon two main trade routes; one at the North and the other at the South. The Northern trade route was dominated by the trade in Kola nuts and at the South, the Ashanti engaged in the Atlantic Slave Trade. A variety of economic industries such as cloth-weaving and metal working industries existed. The Ashanti originally farmed in subsistence until agriculture became extensive during the 19th century.

The Aban was a stone structure that served as a palace for the Asantehene and played the other function of displaying his craft collection. It was constructed in 1822 as a project of Asantehene Osei Bonsu, with the stones and labor provided by the Dutch at Elmina. The palace was destroyed in 1874 during the British invasion and its remains were used to construct a British fort in the late 19th century.

References

- 1 2 3 Ivor Wilks (1989) , p. 1

- ↑ Wilks, Ivor (1992). "On Mentally Mapping Greater Asante: A Study of Time and Motion". The Journal of African History . 33 (2): 175–190. doi:10.1017/S0021853700032199. JSTOR 182997. S2CID 161405742.

- 1 2 Ivor Wilks (1989) , p. 2

- ↑ Ivor Wilks (1989) , pp. 2–3

- ↑ Charney, Michael (2016). "Before and after the wheel: Precolonial and colonial states and transportation in West Africa and mainland Southeast Asia". HumaNetten. 37 (37): 9–38. doi:10.15626/hn.20163702. S2CID 130389976.

- ↑ Ivor Wilks (1989), p. 38

- ↑ Ivor Wilks (1989) , p. 25

- ↑ Eisenstadt, Shmuel Noah.; Abitbol, Michael; Chazan, Naomi (1988). The Early State in African Perspective: Culture, Power, and Division of Labor. Brill. p. 86. ISBN 9004083553.

- ↑ Ivor Wilks (1989) , p. 48

- ↑ Wilks, Ivor (1966). "Aspects of Bureaucratization in Ashanti in the Nineteenth Century". The Journal of African History. 7 (2): 215–232. doi:10.1017/S0021853700006289. JSTOR 179951. S2CID 159872590.

- ↑ Ivor Wilks (1989) , p. 55

- 1 2 Ivor Wilks (1989) , p. 35

- ↑ Blanton, Richard; Fargher, Lane (2008). Collective Action in the Formation of Pre-Modern States. Springer Science+Business Media. p. 140. ISBN 9780387738765. ISSN 1567-8040.

- ↑ Ivor Wilks (1989) , p. 36

- ↑ Thornton, John Kelly (1999). Warfare in Atlantic Africa, 1500-1800. Routledge. p. 73. ISBN 9781135365844.

- ↑ Ivor Wilks (1989) , pp. 3–5

- 1 2 Ivor Wilks (1989) , p. 7

- 1 2 Ivor Wilks (1989) , p. 8

- ↑ Ivor Wilks (1989) , p. 9

- 1 2 3 Ivor Wilks (1989) , pp. 9–10

- ↑ Ivor Wilks (1989) , p. 33–34

- ↑ Dickson, K. B (1961). "The Development of Road Transport in Southern Ghana and Ashanti since about 1850". Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana. 5 (1): 33–42. JSTOR 41405736. S2CID 155808119.

- ↑ Ivor Wilks (1989) , pp. 12–13

Bibliography

- Ivor Wilks (1989). Asante in the Nineteenth Century: The Structure and Evolution of a Political Order. CUP Archive. ISBN 9780521379946 . Retrieved 2020-12-29– via Books.google.com.