In English history, the penal laws were a series of laws that sought to uphold the establishment and State decreed religious monopoly of the Church of England against illegal and underground Catholics and Protestant nonconformists by imposing various forfeitures, civil penalties, and civil disabilities upon recusants from mandatory attendance at weekly Anglican Sunday services. The penal laws in general were repealed in the early 19th century during the process of Catholic Emancipation. Penal actions are civil in nature and were not English common law.

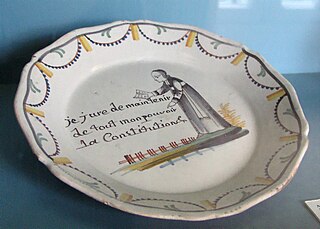

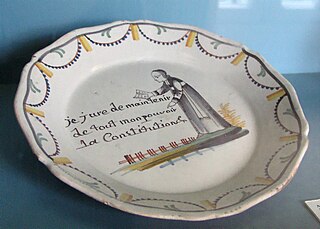

The Civil Constitution of the Clergy was a law passed on 12 July 1790 during the French Revolution, that caused the immediate subordination of most of the Catholic Church in France to the French government. As such, a schism was created, resulting in a French Catholic Church loyal to the Papacy, and a "constitutional church" subject to the French state. The schism was not fully resolved until 1801. King Louis XVI ultimately yielded to the measure after originally opposing it.

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in the kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland, and later the combined United Kingdom in the late 18th century and early 19th century, that involved reducing and removing many of the restrictions on Roman Catholics introduced by the Act of Uniformity, the Test Acts and the penal laws. Requirements to abjure (renounce) the temporal and spiritual authority of the pope and transubstantiation placed major burdens on Roman Catholics.

An Act to prevent the further Growth of Popery was an Act of the Parliament of Ireland that was passed in 1704 designed to suppress Roman Catholicism in Ireland ("Popery"). William Edward Hartpole Lecky called it the most notorious of the Irish Penal Laws.

Cisalpinism was a movement among English Roman Catholics in the late eighteenth century intended to further the cause of Catholic emancipation, i.e. relief from many of the restrictions still in effect that were placed on Roman Catholic British subjects. This view held that allegiance to the Crown was not incompatible with allegiance to the Pope.

Charles Walmesley, OSB was the Roman Catholic Titular Bishop of Rama and Vicar Apostolic of the Western District of England. He was known, especially in Ireland, for predicting the downfall of Protestantism in 1821–5 and the triumphant emergence of the Catholic Church.

The Ecclesiastical Titles Act 1851 was an Act of the British Parliament which made it a criminal offence for anyone outside the established "United Church of England and Ireland" to use any episcopal title "of any city, town or place ... in the United Kingdom". It provided that any property passed to a person under such a title would be forfeit to the Crown. The act was introduced by Prime Minister Lord John Russell in response to anti-Catholic reaction to the 1850 establishment of Catholic dioceses in England and Wales under the papal bull Universalis Ecclesiae. The 1851 act proved ineffective and was repealed 20 years later by the Ecclesiastical Titles Act 1871. Roman Catholic bishops followed the letter of the law but their laity ignored it. The effect was to strengthen the Catholic Church in England, but it also felt persecuted and on the defensive.

The Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829, also known as the Catholic Emancipation Act 1829, removed the sacramental tests that barred Roman Catholics in the United Kingdom from Parliament and from higher offices of the judiciary and state. It was the culmination of a fifty-year process Catholic emancipation which had offered Catholics successive measures of "relief" from the civil and political disabilities to which they had been systematically subject both in Great Britain and in Ireland since the late 17th century.

In Ireland, the penal laws were a series of legal disabilities imposed in the seventeenth, and early eighteenth, centuries on the kingdom's Roman Catholic majority and, to a lesser degree, on Protestant "Dissenters". Enacted by the Irish Parliament, they secured the Protestant Ascendancy by further concentrating property and public office in the hands of those who, as communicants of the established Church of Ireland, subscribed to the Oath of Supremacy. The Oath acknowledged the British monarch as the "supreme governor" of matters both spiritual and temporal, and abjured "all foreign jurisdictions [and] powers"—by implication both the Pope in Rome and the Stuart "Pretender" in the court of the King of France.

The Catholic Church in the United Kingdom is part of the worldwide Catholic Church in communion with the Pope. While there is no ecclesiastical jurisdiction corresponding to the political union, this article refers to the Catholic Church's geographical representation in mainland Britain as well as Northern Ireland, ever since the establishment of the UK's predecessor Kingdom of Great Britain by the Union of the Crowns in 1707.

The Papists Act 1778 is an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain and was the first Act for Roman Catholic relief. Later in 1778 it was also enacted by the Parliament of Ireland.

The Cisalpine Club was an association of Roman Catholic laymen formed in England in the 1790s to promote Cisalpinism, and played a role in the public debate surrounding the progress of Catholic Emancipation.

The English Protestant Reformation was imposed by the English Crown, and submission to its essential points was exacted by the State with post-Reformation oaths. With some solemnity, by oath, test, or formal declaration, English churchmen and others were required to assent to the religious changes, starting in the sixteenth century and continuing for more than 250 years.

John Milner was an English Roman Catholic bishop and controversialist who served as the Vicar Apostolic of the Midland District from 1803 to 1826.

The Roman Catholic Relief Bills were a series of measures introduced over time in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries before the Parliaments of Great Britain and the United Kingdom to remove the restrictions and prohibitions imposed on British and Irish Catholics during the English Reformation. These restrictions had been introduced to enforce the separation of the English church from the Catholic Church which began in 1529 under Henry VIII.

Father Arthur O'Leary, OFMCap was an Irish Capuchin friar and polemical writer.

This article details the history of Christianity in Ireland. Ireland is an island to the north-west of continental Europe. Politically, Ireland is divided between the Republic of Ireland, which covers just under five-sixths of the island, and Northern Ireland, a part of the United Kingdom, which covers the remainder and is located in the north-east of the island. All main churches are organised on an all-island basis. Roman Catholicism is the largest religious denomination, representing over 73% for the island and about 78.3% of the Republic of Ireland.

Anti-Catholicism in the United Kingdom dates back to Roman times. Attacks on the Church from a Protestant angle mostly began with the English and Irish Reformations which were launched by King Henry VIII and the Scottish Reformation which was led by John Knox. Within England, the Act of Supremacy 1534 declared the English crown to be "the only supreme head on earth of the Church in England" in place of the Pope. Any act of allegiance to the latter was considered treasonous because the papacy claimed both spiritual and political power over its followers. Ireland was brought under direct English control starting in 1536 during the Tudor conquest of Ireland. The Scottish Reformation in 1560 abolished Catholic ecclesiastical structures and rendered Catholic practice illegal in Scotland. Today, anti-Catholicism remains common in the United Kingdom, with particular relevance in Scotland and Northern Ireland.

The Toleration Act 1688, also referred to as the Act of Toleration, was an Act of the Parliament of England. Passed in the aftermath of the Glorious Revolution, it received royal assent on 24 May 1689.

The Catholic Committee was a county association in late 18th-century Ireland that campaigned to relieve Catholics of their civil and political disabilities under the kingdom's Protestant Ascendancy. After their organisation of a national Catholic Convention helped secure repeal of most of the remaining Penal Laws in 1793, the Committee dissolved. Members briefly reconvened the following year when a new British Viceroy, William Fitzwilliam, raised hopes of further reform, including lifting the sacramental bar to Catholics entering the Irish Parliament. When these were dashed by his early recall to London, many who had been mobilized by the Committee and by the Convention, defied their bishops, and joined the United Irishmen as they organised for a republican insurrection.