The Sacra Parallela is a Byzantine florilegium of quotes in Greek from the Bible and patristic texts used in the instruction of ethics, morals and asceticism. [1]

The Sacra Parallela is a Byzantine florilegium of quotes in Greek from the Bible and patristic texts used in the instruction of ethics, morals and asceticism. [1]

The Sacra Parallela was compiled in the eighth century, probably in Palestine. It is usually attributed to John of Damascus, but this is questionable. A tenth-century manuscript names the compilers as "Leontios the priest and John"; the latter is unidentified. [2] It was first printed in 1577. [3] This edition was based on a fifteenth-century manuscript (codex Vat. gr. 1236).

In its original state, the Sacra Parallela existed as three separate books which discussed dealing with God, with Man and with Virtues and Vices respectively. [1] However, the original codex is currently lost to us. Research on this piece is based on later recensions that were made when the original three books became one. [4]

John of Damascus was a proponent for the use of icons during the rise of iconoclasm. Serving as a priest at Mar Saba near Jerusalem, John of Damascus lived under Muslim rule and was safe from persecution for his iconophile views. This could explain why the Parisian manuscript is so heavily illuminated, something not associated with texts that did not tell a story. Although this does not prove his position as author, it does strengthen the possibility that he had ties to the Paris manuscript. [5]

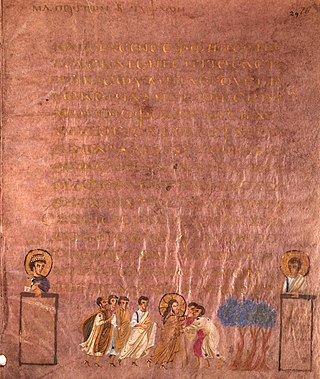

There are three commonly known recensions: The Vatican, the Rupefucaldian and the Parisinus Graecus 923. They were revealed in a study done by Karl Holl in 1897. However, he found that although the Parisinus Graecus 923, a ninth-century piece, was related to the other two recensions, it did not agree with them. Regardless of Holl's findings, due to the manuscript's creation in a time of iconoclasm and its rich use of gold, the piece is still considered very valuable and has been studied to some extent. [3] The images can help researchers reconstruct lost cycles of miniatures prior to iconoclasm. [6] The Parisinus Graecus 923 is the largest and only illuminated Greek florilegium to have survived from the Byzantine era. [7]

The Parisian manuscript is 35.6 x 26.5 centimeters and is bound in pressed leather with clasps dated to the fifteenth century. The contents are written onto 394 folios of thick parchment in sloping uncial above the line. The script is organized into two columns of 36 lines that have 13 to 17 letters each. The height of the letters is around 3 millimeters. [8] In the Parisian codex, the excerpts that are placed under each topic follows this order: Old Testament, New Testament, Church Fathers and philosopher Philo Judaeus and the historian Flavius Josephus. [7]

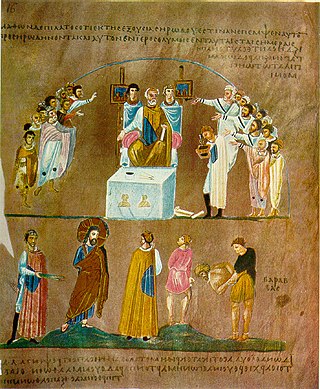

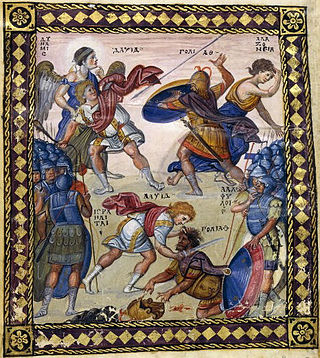

Of the 1,658 illustrations within the Sacra Parallela Parisinus Graecus 923, approximately 402 are scenic illustrations and 1,256 are portraits. The placement of images in a manuscript usually follows a pattern. However, as a result of its structure as a florilegium text, the author of the Sacra Parallela lacked any notion of design when distributing the images. Some pages are full of illustrations closely followed by several that do not have any. [9] Passages from the Church Fathers are the lengthiest and since patristic texts rarely have narrative illustrations, they are responsible for the long gaps that lack images. [10] The use of gold was not limited and decorated the draperies, architecture and pieces of landscape within the manuscript. [11] This use of gold was intended to create a spiritual and dematerializing effect. However, it was not used due to a lack of stylistic thought. In fact, the coloring of some of the faces actually reveals a good command of the effect of colors left over from the classical tradition. [12]

The double lines used for the folds in the draperies are not consistent in style hinting at the fact that there was more than one illuminator working on this manuscript. This is not considered unusual due to the sheer number of illustrations. However, this disparity can also be seen in the design and colors used for the faces. Some individuals, such as Josephus Flavius, show a high degree of individuality. Others, like John Chrysostom, are dull and expressionless. Researchers attribute this second style of facial expressions to repetition and not poor skills. Expressions were used when the text called for it, such as grief when Jacob saw Joseph's blood-ridden coat. The artists were also skilled as realistically depicting gestures and motions, shown through Abraham's firm grip on Sarah's wrist. [13] Overall, the styles that were used by the various artists for the creation of the Sacra Parallela were remarkably similar. The variations are not attributed to the different artists, but the fact that the artists gave the most attention to the scenes that they liked and finished the rest in a routine manner. [14]

The Vienna Genesis, designated by siglum L (Ralphs), is an illuminated manuscript, probably produced in Syria in the first half of the 6th century. It is one of the oldest well-preserved, surviving, illustrated biblical codices; only the Garima Gospels of Ethiopia, dating to the 5th and 6th centuries, are as old or older.

The Rossano Gospels, designated by 042 or Σ, ε 18 (Soden), held at the cathedral of Rossano in Italy, is a 6th-century illuminated manuscript Gospel Book written following the reconquest of the Italian peninsula by the Byzantine Empire. Also known as Codex purpureus Rossanensis due to the reddish-purple appearance of its pages, the codex is one of the oldest surviving illuminated manuscripts of the New Testament. The manuscript is famous for its prefatory cycle of miniatures of subjects from the Life of Christ, arranged in two tiers on the page, sometimes with small Old Testament prophet portraits below, prefiguring and pointing up to events described in the New Testament scene above.

Saint Catherine's Monastery, officially the Sacred Autonomous Royal Monastery of Saint Catherine of the Holy and God-Trodden Mount Sinai, is a Christian monastery located in the Sinai Peninsula of Egypt. Located at the foot of Mount Sinai, it was built between 548 and 565, and is the world's oldest continuously inhabited Christian monastery.

Byzantine art comprises the body of artistic products of the Eastern Roman Empire, as well as the nations and states that inherited culturally from the empire. Though the empire itself emerged from the decline of western Rome and lasted until the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, the start date of the Byzantine period is rather clearer in art history than in political history, if still imprecise. Many Eastern Orthodox states in Eastern Europe, as well as to some degree the Islamic states of the eastern Mediterranean, preserved many aspects of the empire's culture and art for centuries afterward.

The Vergilius Vaticanus, also known as Vatican Virgil, is a Late Antique illuminated manuscript containing fragments of Virgil's Aeneid and Georgics. It was made in Rome in around 400 CE, and is one of the oldest surviving sources for the text of the Aeneid. It is the oldest and one of only three ancient illustrated manuscripts of classical literature.

The Vergilius Romanus, also known as the Roman Vergil, is a 5th-century illustrated manuscript of the works of Virgil. It contains the Aeneid, the Georgics, and some of the Eclogues. It is one of the oldest and most important Vergilian manuscripts. It is 332 by 323 mm with 309 vellum folios. It was written in rustic capitals with 18 lines per page.

The Cotton Genesis is a 4th- or 5th-century Greek Illuminated manuscript copy of the Book of Genesis. It was a luxury manuscript with many miniatures. It is one of the oldest illustrated biblical codices to survive to the modern period. Most of the manuscript was destroyed in the Cotton library fire in 1731, leaving only eighteen charred, shrunken scraps of vellum. From the remnants, the manuscript appears to have been more than 440 pages with approximately 340–360 illustrations that were framed and inserted into the text column. Many miniatures were also copied in the 17th century and are now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris.

The Sinope Gospels, designated by O or 023, ε 21 (Soden), also known as the Codex Sinopensis, is a fragment of a 6th-century illuminated Greek Gospel Book. Along with the Rossano Gospels, the Sinope Gospels has been dated, on the basis of the style of the miniatures, to the mid 6th-century. The Rossano Gospels, however, are considered to be earlier. Like Rossanensis and the Vienna Genesis, the Sinope Gospels are written on purple dyed vellum.

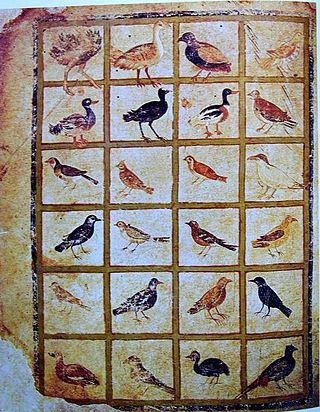

The Vienna Dioscurides or Vienna Dioscorides is an early 6th-century Byzantine Greek illuminated manuscript of an even earlier 1st century AD work, De materia medica by Pedanius Dioscorides in uncial script. It is an important and rare example of a late antique scientific text. After residing in Constantinople for just over a thousand years, the text passed to the Holy Roman Emperor in Vienna in the 16th century, a century after the city fell to the Ottoman Empire.

The Ambrosian Iliad or Ilias Picta is a 5th-century illuminated manuscript on vellum, which depicts the entirety of Homer's Iliad, including battle scenes and noble scenes. It is considered unique due to being the only set of ancient illustrations that depict scenes from the Iliad. The Ambrosian Iliad consists of 52 miniatures, each labeled numerically. It is thought to have been created in Alexandria, given the flattened and angular Hellenistic figures, which are considered typical of Alexandrian art in late antiquity, in approximately 500 AD, possibly by multiple artists. The author(s) first drew the figures nude and then painted the clothes on, much like in Greek vase painting. In the 11th century, the miniatures were cut out of the original manuscript and pasted into a Siculo-Calabrian codex of Homeric texts.

The Paris Psalter is a Byzantine illuminated manuscript, 38 x 26.5 cm in size, containing 449 folios and 14 full-page miniatures. The Paris Psalter is considered a key monument of the so-called Macedonian Renaissance, a 10th-century renewal of interest in classical art closely identified with the emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (909-959) and his immediate successors.

The Naples Dioscurides, in the Biblioteca Nazionale, Naples, is an early 7th-century secular illuminated manuscript Greek herbal. The book has 172 folios and a page size of 29.7 x 14 cm and the text is a redaction of De Materia Medica by the 1st century Greek military physician Dioscorides, with descriptions of plants and their medicinal uses. Unlike De Materia Medica, the text is arranged alphabetically by plant.

Kurt Weitzmann was a German turned American art historian who was a leading figure in the study of Late Antique and Byzantine art in particular.

A patristic anthology, commonly called a florilegium, is a systematic collections of excerpts from the works of the Church Fathers and other ecclesiastical writers of the early period, compiled with a view to serve dogmatic or ethical purposes. These encyclopedic compilations are a characteristic product of the later Byzantine theological school, and form a very considerable branch of the extensive literature of the Greek Catenæ. They frequently embody the only remains of some patristic writings.

Codex Marchalianus, designated by siglum Q, is a 6th-century Greek manuscript copy of the Greek version of the Hebrew Bible known as the Septuagint. It is now in the Vatican Library. The text was written on vellum in uncial letters. Palaeographically it has been assigned to the 6th century. Marginal annotations were later added to the copy of the Scripture text, the early ones being of importance for a study of the history of the Septuagint.

Codex Parisinus Graecus 456, designated by siglum H, manuscript of Origen's Philocalia and Contra Celsum.

The Vatican Terence, or Codex Vaticanus Latinus 3868, is a 9th-century illuminated manuscript of the Latin comedies of Publius Terentius Afer, housed in the Vatican Library. According to art-historical analysis the manuscript was copied from a model of the 3rd century. The manuscript is referred to in the apparatus criticus of modern editions as "C".

Christ Pantocrator of Saint Catherine's Monastery is one of the oldest Byzantine religious icons, dating from the 6th century AD. The earliest known surviving depiction of Jesus Christ as Pantocrator, it is regarded by historians and scholars among the most important and recognizable works in the study of Byzantine art as well as Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholic Christianity.

Byzantine illuminated manuscripts were produced across the Byzantine Empire, some in monasteries but others in imperial or commercial workshops. Religious images or icons were made in Byzantine art in many different media: mosaics, paintings, small statues and illuminated manuscripts. Monasteries produced many of the illuminated manuscripts devoted to religious works using the illustrations to highlight specific parts of text, a saints' martyrdom for example, while others were used for devotional purposes similar to icons. These religious manuscripts were most commissioned by patrons and were used for private worship but also gifted to churches to be used in services.