The Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of June 18, 1934, or the Wheeler–Howard Act, was U.S. federal legislation that dealt with the status of American Indians in the United States. It was the centerpiece of what has been often called the "Indian New Deal". The major goal was to reverse the traditional goal of cultural assimilation of Native Americans into American society and to strengthen, encourage and perpetuate the tribes and their historic Native American cultures in the United States.

Pinehill or Pine Hill is a census-designated place in Cibola County, New Mexico, United States. It is located on the Ramah Navajo Indian Reservation. The population was 88 at the 2010 census. The location of the CDP in 2010 had become the location of the Mountain View CDP as of the 2020 census, while a new CDP named "Pinehill" was listed 8 miles (13 km) further south, at a point 4 miles (6 km) southeast of Candy Kitchen.

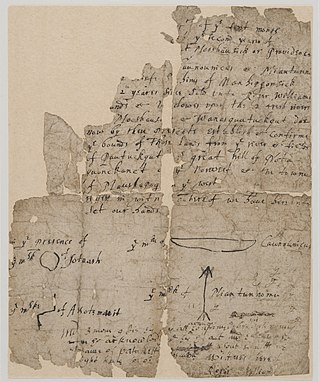

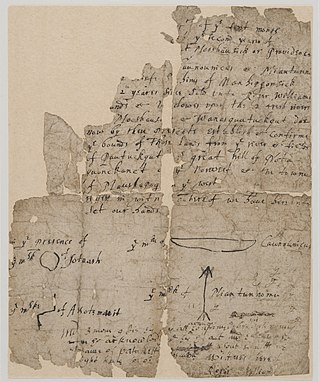

The Nonintercourse Act is the collective name given to six statutes passed by the United States Congress in 1790, 1793, 1796, 1799, 1802, and 1834 to set boundaries of Native American reservations. The various acts were also intended to regulate commerce between settlers and the natives. The most notable provisions of the act regulate the inalienability of aboriginal title in the United States, a continuing source of litigation for almost 200 years. The prohibition on purchases of Indian lands without the approval of the federal government has its origins in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and the Confederation Congress Proclamation of 1783.

The Ramah Navajo Indian Reservation is a non-contiguous section of the Navajo Nation lying in parts of west-central Cibola and southern McKinley counties in New Mexico, United States, just east and southeast of the Zuni Indian Reservation. It has a land area of 230.675 sq mi (597.445 km²), over 95 percent of which is designated as off-reservation trust land. According to the 2000 census, the resident population is 2,167 persons. The Ramah Reservation's land area is less than one percent of the Navajo Nation's total area.

Kevin K. Washburn is an American law professor, former dean of the University of New Mexico School of Law, and current Dean of the University of Iowa College of Law. He served in the administration of President Barack Obama as Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs at the U.S. Department of the Interior from 2012 to 2016. Washburn has also been a federal prosecutor, a trial attorney at the U.S. Department of Justice, and the General Counsel of the National Indian Gaming Commission. Washburn is a member of the Chickasaw Nation of Oklahoma, a federally-recognized Native American tribe.

Native American self-determination refers to the social movements, legislation and beliefs by which the Native American tribes in the United States exercise self-governance and decision-making on issues that affect their own people.

Santa Clara Pueblo v. Martinez, 436 U.S. 49 (1978), was a landmark case in the area of federal Indian law involving issues of great importance to the meaning of tribal sovereignty in the contemporary United States. The Supreme Court sustained a law passed by the governing body of the Santa Clara Pueblo that explicitly discriminated on the basis of sex. In so doing, the Court advanced a theory of tribal sovereignty that weighed the interests of tribes sufficient to justify a law that, had it been passed by a state legislature or Congress, would have almost certainly been struck down as a violation of equal protection.

Carcieri v. Salazar, 555 U.S. 379 (2009), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that the federal government could not take land into trust that was acquired by the Narragansett Tribe in the late 20th century, as it was not federally recognized until 1983. While well documented in historic records and surviving as a community, the tribe was largely dispossessed of its lands while under guardianship by the state of Rhode Island before suing in the 20th century.

Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma v. Leavitt, 543 U.S. 631 (2005), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that a contract with the Federal Government to reimburse the tribe for health care costs was binding, despite the failure of Congress to appropriate funds for those costs.

United States v. White Mountain Apache Tribe, 537 U.S. 465 (2003), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held in a 5–4 decision that when the federal government used land or property held in trust for an Indian tribe, it had the duty to maintain that land or property and was liable for any damages for a breach of that duty. In the 1870s, the White Mountain Apache Tribe was placed on a reservation in Arizona. The case involved Fort Apache, a collection of buildings on the reservation which were transferred to the tribe by the United States Congress in 1960.

The United States was the first jurisdiction to acknowledge the common law doctrine of aboriginal title. Native American tribes and nations establish aboriginal title by actual, continuous, and exclusive use and occupancy for a "long time." Individuals may also establish aboriginal title, if their ancestors held title as individuals. Unlike other jurisdictions, the content of aboriginal title is not limited to historical or traditional land uses. Aboriginal title may not be alienated, except to the federal government or with the approval of Congress. Aboriginal title is distinct from the lands Native Americans own in fee simple and occupy under federal trust.

Merrion v. Jicarilla Apache Tribe, 455 U.S. 130 (1982), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States holding that an Indian tribe has the authority to impose taxes on non-Indians that are conducting business on the reservation as an inherent power under their tribal sovereignty.

South Carolina v. Catawba Indian Tribe, Inc., 476 U.S. 498 (1986), is an important U.S. Supreme Court precedent for aboriginal title in the United States decided in the wake of County of Oneida v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York State (1985). Distinguishing Oneida II, the Court held that federal policy did not preclude the application of a state statute of limitations to the land claim of a tribe that had been terminated, such as the Catawba tribe.

The Connecticut Indian Land Claims Settlement was an Indian Land Claims Settlement passed by the United States Congress in 1983. The settlement act ended a lawsuit by the Mashantucket Pequot Tribe to recover 800 acres of their 1666 reservation in Ledyard, Connecticut. The state sold this property in 1855 without gaining ratification by the Senate. In a federal land claims suit, the Mashantucket Pequot charged that the sale was in violation of the Nonintercourse Act that regulates commerce between Native Americans and non-Indians.

Kerr-McGee v. Navajo Tribe, 471 U.S. 195 (1985), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that an Indian tribe is not required to obtain the approval of the Secretary of the Interior in order to impose taxes on non-tribal persons or entities doing business on a reservation.

Williams v. Lee, 358 U.S. 217 (1959), was a landmark case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that the State of Arizona does not have jurisdiction to try a civil case between a non-Indian doing business on a reservation with tribal members who reside on the reservation, the proper forum for such cases being the tribal court.

Menominee Tribe of Wis. v. United States, 577 U.S. ___ (2016), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States clarified when litigants are entitled to equitable tolling of a statute of limitations. In a unanimous opinion written by Justice Samuel Alito, the Court held that the plaintiff in this case was not entitled to equitable tolling of the statute of limitations because they did not demonstrate that "extraordinary circumstances" prevented the timely filing of the lawsuit.

Patchak v. Zinke, 583 U.S. ___ (2018), is a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court upheld the Gun Lake Trust Land Reaffirmation Act, which precludes federal courts from hearing lawsuits involving a particular parcel of land. Although six Justices agreed that the Gun Lake Act was constitutional, they could not agree on why. In an opinion issued by Justice Thomas, a plurality of the Court read the statute to strip federal courts of jurisdiction over cases involving the property and held that this did not violate Article Three of the United States Constitution. In contrast, Justices Ginsburg and Sotomayor, both of whom concurred in the judgment, upheld the Act as a restoration of the government's sovereign immunity. Chief Justice Roberts, writing for himself and Justices Kennedy and Gorsuch, dissented on the ground that the statute intruded on the judicial power, in violation of Article III.

Haaland v. Brackeen was a Supreme Court of the United States case brought by the states of Texas, Louisiana, and Indiana, and individual plaintiffs, that sought to declare the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) unconstitutional. In addition to Haaland v. Brackeen, three additional cases were consolidated to be heard at the same time: Cherokee Nation v. Brackeen, Texas v. Haaland, and Brackeen v. Haaland.

Pine Hill Schools is a K-12 tribal school system operated by the Ramah Navajo School Board, Inc. (RNSB), in association with the Bureau of Indian Education (BIE), in Pine Hill, New Mexico.