Fair use is a doctrine in United States law that permits limited use of copyrighted material without having to first acquire permission from the copyright holder. Fair use is one of the limitations to copyright intended to balance the interests of copyright holders with the public interest in the wider distribution and use of creative works by allowing as a defense to copyright infringement claims certain limited uses that might otherwise be considered infringement. Unlike "fair dealing" rights that exist in most countries with a British legal history, the fair use right is a general exception that applies to all different kinds of uses with all types of works and turns on a flexible proportionality test that examines the purpose of the use, the amount used, and the impact on the market of the original work.

Itar-Tass Russian News Agency v. Russian Kurier, Inc., 153 F.3d 82, was a copyright case about the Russian language weekly Russian Kurier in New York City that had copied and published various materials from Russian newspapers and news agency reports of Itar-TASS. The case was ultimately decided by the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. The decision was widely commented upon and the case is considered a landmark case because the court defined rules applicable in the U.S. on the extent to which the copyright laws of the country of origin or those of the U.S. apply in international disputes over copyright. The court held that to determine whether a claimant actually held the copyright on a work, the laws of the country of origin usually applied, but that to decide whether a copyright infringement had occurred and for possible remedies, the laws of the country where the infringement was claimed applied.

Wheaton v. Peters, 33 U.S. 591 (1834), was the first United States Supreme Court ruling on copyright. The case upheld the power of Congress to make a grant of copyright protection subject to conditions and rejected the doctrine of a common law copyright in published works. The Court also declared that there could be no copyright in the Court's own judicial decisions.

Harper & Row v. Nation Enterprises, 471 U.S. 539 (1985), was a United States Supreme Court decision in which public interest in learning about a historical figure's impressions of a historic event was held not to be sufficient to show fair use of material otherwise protected by copyright. Defendant, The Nation, had summarized and quoted substantially from A Time to Heal, President Gerald Ford's forthcoming memoir of his decision to pardon former president Richard Nixon. When Harper & Row, who held the rights to A Time to Heal, brought suit, The Nation asserted that its use of the book was protected under the doctrine of fair use, because of the great public interest in a historical figure's account of a historic incident. The Court rejected this argument holding that the right of first publication was important enough to find in favor of Harper.

Bare-faced Messiah: The True Story of L. Ron Hubbard is a posthumous biography of Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard by British journalist Russell Miller. First published in the United Kingdom on 26 October 1987, the book takes a critical perspective, challenging the Church of Scientology's account of Hubbard's life and work. It quotes extensively from official documents acquired using the Freedom of Information Act and from Hubbard's personal papers, which were obtained via a defector from Scientology. It was also published in Australia, Canada and the United States.

Jon Ormond Newman is a Senior United States Circuit Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.

The Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, also known as the CDPA, is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that received Royal Assent on 15 November 1988. It reformulates almost completely the statutory basis of copyright law in the United Kingdom, which had, until then, been governed by the Copyright Act 1956 (c. 74). It also creates an unregistered design right, and contains a number of modifications to the law of the United Kingdom on Registered Designs and patents.

Fanfiction has encountered problems with intellectual property law due to usage of copyrighted characters without the original creator or copyright owner's consent.

Roger Jeffrey Miner was a United States Circuit Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit and a United States District Judge of the United States District Court for the Northern District of New York.

In copyright law, related rights are the rights of a creative work not connected with the work's actual author. It is used in opposition to the term "authors' rights". Neighbouring rights is a more literal translation of the original French droits voisins. Both authors' rights and related rights are copyrights in the sense of English or U.S. law.

Castle Rock Entertainment Inc. v. Carol Publishing Group, 150 F.3d 132, was a U.S. copyright infringement case involving the popular American sitcom Seinfeld. Some U.S. copyright law courses use the case to illustrate modern application of the fair use doctrine. The United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit upheld a lower court's summary judgment that the defendant had committed copyright infringement. The decision is noteworthy for classifying Seinfeld trivia not as unprotected facts, but as protectable expression. The court also rejected the defendant's fair use defense finding that any transformative purpose possessed in the derivative work was "slight to non-existent" under the Supreme Court ruling in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569 (1994).

Feist Publications, Inc., v. Rural Telephone Service Co., 499 U.S. 340 (1991), was a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States establishing that information alone without a minimum of original creativity cannot be protected by copyright. In the case appealed, Feist had copied information from Rural's telephone listings to include in its own, after Rural had refused to license the information. Rural sued for copyright infringement. The Court ruled that information contained in Rural's phone directory was not copyrightable and that therefore no infringement existed.

In copyright law, a derivative work is an expressive creation that includes major copyrightable elements of an original, previously created first work. The derivative work becomes a second, separate work independent in form from the first. The transformation, modification or adaptation of the work must be substantial and bear its author's personality sufficiently to be original and thus protected by copyright. Translations, cinematic adaptations and musical arrangements are common types of derivative works.

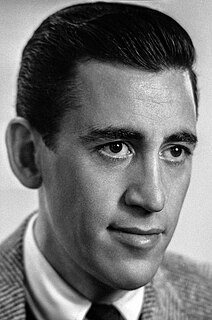

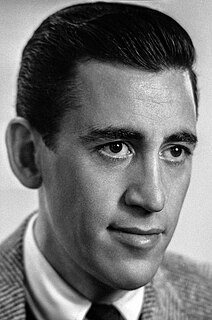

Jerome David Salinger was an American author best known for his 1951 novel The Catcher in the Rye. Before its publication, Salinger published several short stories in Story magazine and served in World War II. In 1948, his critically acclaimed story "A Perfect Day for Bananafish" appeared in The New Yorker, which published much of his later work.

Perfect 10, Inc. v. Amazon.com, Inc., 508 F.3d 1146 was a case in the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit involving Perfect 10, Inc., Amazon.com, Inc. and Google, Inc. The court held that Google's framing and hyperlinking as part of an image search engine constituted a fair use of Perfect 10's images because the use was highly transformative, overturning most of the district court's decision.

Gyles v Wilcox (1740) 26 ER 489 was a decision of the Court of Chancery of England that established the doctrine of fair abridgement, which would later evolve into the concept of fair use. The case was heard and the opinion written by Philip Yorke, 1st Earl of Hardwicke, and concerned Fletcher Gyles, a bookseller who had published a copy of Matthew Hale's Pleas of the Crown. Soon after the initial publication, the publishers Wilcox and Nutt hired a writer named Barrow to abridge the book, and repackaged it as Modern Crown Law. Gyles sued for a stay on the book's publishing, claiming his rights under the Statute of Anne had been infringed.

Fair dealing is a statutory exception to copyright infringement, and is also referred to as a user's right. According to the Supreme Court of Canada, it is more than a simple defence; it is an integral part of the Copyright Act of Canada, providing balance between the rights of owners and users. To qualify under the fair dealing exception, the dealing must be for a purpose enumerated in sections 29, 29.1 or 29.2 of the Copyright Act of Canada, and the dealing must be considered fair as per the criteria established by the Supreme Court of Canada.

Paraphrasing of copyrighted material may, under certain circumstances, constitute copyright infringement. In most countries that have national copyright laws, copyright applies to the original expression in a work rather than to the meanings or ideas being expressed. Whether a paraphrase is an infringement of expression, or a permissible restatement of an idea, is not a binary question but a matter of degree. Copyright law in common law countries tries to avoid theoretical discussion of the nature of ideas and expression such as this, taking a more pragmatic view of what is called the idea/expression dichotomy. The acceptable degree of difference between a prior work and a paraphrase depends on a variety of factors and ultimately depends on the judgement of the court in each individual case.

Nutt v. National Institute Inc. was an early case in which it was found that copyright extended beyond the words of a work. The court found that "The infringement need not be a complete or exact copy. Paraphrasing or copying with evasion is an infringement, even though there may be little or no conceivable identity between the two."

Wright v. Warner Books (1991) was a case in which the widow of the author Richard Wright (1908–1960) claimed that his biographer, the poet and writer Margaret Walker (1915–1998), had infringed copyright by using content from some of Wright's unpublished letters and journals. The court took into account the recent ruling in Salinger v. Random House, Inc. (1987), which had found that a copyright owner had the right to control first publication, but found in favor of Walker after weighing all factors. The case had broad implications by allowing the use of library special collections for academic research.