Related Research Articles

Slavery in the colonial history of the United States refers to the institution of slavery that existed in the European colonies in North America which eventually became part of the United States of America. Slavery developed due to a combination of factors, primarily the labour demands for establishing and maintaining European colonies, which had resulted in the Atlantic slave trade. Slavery existed in every European colony in the Americas during the early modern period, and both Africans and indigenous peoples were targets of enslavement by European colonists during the era.

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered voluntarily for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment, or imposed involuntarily as a judicial punishment. The practice has been compared to the similar institution of slavery, although there are differences.

Molly Brant, also known as Mary Brant, Konwatsi'tsiaienni, and Degonwadonti, was a Mohawk leader in British New York and Upper Canada in the era of the American Revolution. Living in the Province of New York, she was the consort of Sir William Johnson, the British Superintendent of Indian Affairs, with whom she had eight children. Joseph Brant, who became a Mohawk leader and war chief, was her younger brother.

In societies that regard some races or ethnic groups of people as dominant or superior and others as subordinate or inferior, hypodescent refers to the automatic assignment of children of a mixed union to the subordinate group. The opposite practice is hyperdescent, in which children are assigned to the race that is considered dominant or superior.

Sally Miller, born Salomé Müller, was an American woman enslaved sometime in the late 1810s, whose freedom suit in Louisiana was based on her claimed status as a free German immigrant and indentured servant born to non-enslaved parents. The case attracted wide attention and publicity because of the issue of "white" slavery. In Sally Miller v. Louis Belmonti, the Louisiana Supreme Court ruled in her favor, and Miller gained freedom.

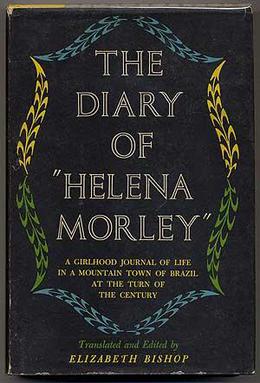

Alice Dayrell Caldeira Brant was a Brazilian juvenile writer. When she was a teenager, she kept a diary, which describes life in Diamantina, Minas Gerais, Brazil which was then published in 1942. The diary was published under a pen name Helena Morley. When it was originally published it was in portuguese under the title Minha Vida de Menina. The diary was then translated in to English by Elizabeth Bishop in 1957.

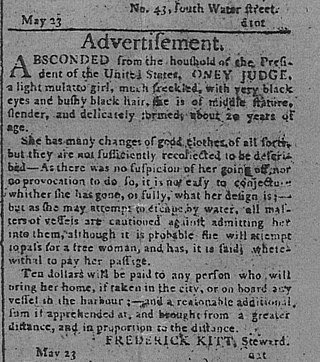

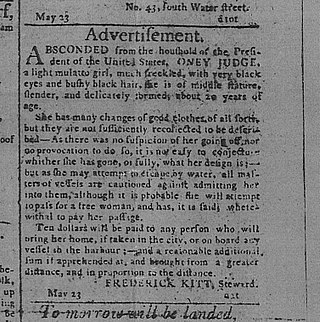

Ona "Oney" Judge Staines was an enslaved woman owned by the Washington family, first at the family's plantation at Mount Vernon and later, after George Washington became president, at the President's House in Philadelphia, then the nation's capital city. In her early twenties, she absconded, becoming a fugitive slave, after learning that Martha Washington had intended to transfer ownership of her to her granddaughter, known to have a horrible temper. She fled to New Hampshire, where she married, had children, and converted to Christianity. Though she was never formally freed, the Washington family ultimately stopped pressing her to return to Virginia after George Washington's death.

Living in a wide range of circumstances and possessing the intersecting identity of both black and female, enslaved women of African descent had nuanced experiences of slavery. Historian Deborah Gray White explains that "the uniqueness of the African-American female's situation is that she stands at the crossroads of two of the most well-developed ideologies in America, that regarding women and that regarding the Negro." Beginning as early on in enslavement as the voyage on the middle passage, enslaved women received different treatment due to their gender. In regard to physical labor and hardship, enslaved women received similar treatment to their male counterparts, but they also frequently experienced sexual abuse at the hand of enslavers who used stereotypes of black women’s hypersexuality as justification.

Women in the American Revolution played various roles depending on their social status, race and political views.

When the Dutch and Swedes established colonies in the Delaware Valley of what is now Pennsylvania, in North America, they quickly imported enslaved Africans for labor; the Dutch also transported them south from their colony of New Netherland. Enslavement was documented in this area as early as 1639. William Penn and the colonists who settled in Pennsylvania tolerated slavery. Still, the English Quakers and later German immigrants were among the first to speak out against it. Many colonial Methodists and Baptists also opposed it on religious grounds. During the Great Awakening of the late 18th century, their preachers urged slaveholders to free their slaves. High British tariffs in the 18th century discouraged the importation of additional slaves, and encouraged the use of white indentured servants and free labor.

Growdon Mansion, also known as Trevose Manor, is a local historical landmark in Bensalem Township, Pennsylvania, United States. It played an important role in early Bucks County history. The mansion sits along the Neshaminy Creek in Bensalem, a township that borders the northeast section of Philadelphia, in the northeastern United States.

Indentured servitude in Pennsylvania (1682-1820s): The institution of indentured servitude has a significant place in the history of labor in Pennsylvania. From the founding of the colony (1681/2) to the early post-revolution period (1820s), indentured servants contributed considerably to the development of agriculture and various industries in Pennsylvania. Moreover, Pennsylvania itself has a notable place in the broader history of indentured servitude in North America. As Cheesman Herrick stated, "This system of labor was more important to Pennsylvania than it was to any other colony or state; it continued longer in Pennsylvania than elsewhere."

Elizabeth Porter Phelps (1747–1817) was a member of the eighteenth-century rural gentry in western Massachusetts; she is also recognized as an important diarist from late 18th century and early 19th century in Hadley, Massachusetts (USA).

Elizabeth Graeme Fergusson, or Betsy Graeme; was an American poet and writer, known for The Dream (1768). She held literary salon gatherings called "attic evenings", based upon French salons. Her attendees included Jacob Duché, Francis Hopkinson, Benjamin Rush, and her niece, Anna Young Smith. She wrote poetry and a wide range of works, taught writing, and mentored women writers, like Annis Boudinot Stockton and Hannah Griffitts.

Sophie Lewis Drinker was an American author, musician, and musicologist. She is considered a founder of women's musicological and gender studies.

Catherine Ann Janvier was an American artist, author, and translator. Before she married, she had an established career as an artist and teacher under the name Catherine Ann Drinker.

Indentured servitude in British America was the prominent system of labor in the British American colonies until it was eventually supplanted by slavery. During its time, the system was so prominent that more than half of all immigrants to British colonies south of New England were white servants, and that nearly half of total white immigration to the Thirteen Colonies came under indenture. By the beginning of the American Revolutionary War in 1775, only 2 to 3 percent of the colonial labor force was composed of indentured servants.

Rebecca Dickinson was an American gownmaker who lived during the mid-to-late eighteenth century and the early nineteenth century. She is significant as the author of a journal in which she writes about her life as an artisan in the context of a woman actively engaging in the economy and a Calvinist in New England in the years following the Revolutionary War (1787-1802). Throughout her life, Dickinson chose to live as a single woman in Hatfield, Massachusetts, sustaining herself through her trade. Her surviving journal documents her struggle to understand her singlehood in the context of her faith. Her diary also allows a glimpse into the lives of people, especially women, living through extremely influential historical events.

Mary Penry was a Welsh-born woman in colonial Pennsylvania. As a longtime member of the Moravian community at Lititz, she served as "diarist, accountant and guide" for the single sisters' house.

Elizabeth Sandwith Drinker was a Quaker woman of late 18th century North America who kept a diary from 1758 to 1807. This 2,100 page diary was first published in 1889 and sheds light on daily life in Philadelphia, the Society of Friends, family and gender roles, political issues and the American Revolution, and innovations in medical practices.

References

- ↑ Smith, Merill (2010). Women's Roles in Eighteenth- Century America. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 20, 21.

- 1 2 Hirsch, Alison Duncan (Autumn 2001). "Uncovering 'the Hidden History of Mestizo America' in Elizabeth Drinker's Diary: Interracial Relationships in Late 18th-Century Philadelphia". Pennsylvania History. 68 (4): 501.

- ↑ Merrill Smith, Women's Roles in 18th-century America", p. 19

- 1 2 3 Berkin, Carol (1996). First Generations: Women in Colonial America. New York: Hill and Wang. pp. 101, 106.

- ↑ Salinger, Sharon V. (Jan 1983). "'Send No More Women': Female Servants in Eighteenth-Century Philadelphia". Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 107: 40.

- ↑ Berkin, Carole (1996). First Generations: Women in Colonial America. NY: Hill and Wang. pp. 101, 106.

- ↑ Berkin, 101; Smith.

- ↑ Salinger, p. 501.

- ↑ Salinger, Sharon V. (Jan 1983). "'Send No More Women': Female Servants in Eighteenth-Century Philadelphia". Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 107: 40–41.

- ↑ Smith, Women's Roles, p. 20]

- ↑ Smith, p. 20.

- ↑ Hirsch, Alison (Autumn 2001). "Uncovering "the Hidden History of Mestizo America" in Elizabeth Drinker's Diary: Interracial Relationships in Late Eighteenth-Century Philadelphia". Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies. 68 (4): 483–506. JSTOR 27774362.

- ↑ Smith, p. 19

- ↑ Smith, p. 20]

- ↑ Smith, Women's Roles p. 20-21

- ↑ Smith, 20-21.

- ↑ Salinger, Sharon V. (Jan 1983). "'Send No More Women': Female Servants in Eighteenth-Century Philadelphia". Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 107: 41.

- ↑ Smith, Women's Roles, p. 20-21.

- ↑ Hirsch, Alison Duncan (Autumn 2001). "Uncovering 'the Hidden History of Mestizo America' in Elizabeth Drinker's Diary: Interracial Relationships in Late 18th-Century Philadelphia". Pennsylvania History. 68 (4): 505.

- ↑ Lyons, Clare (2012). Sex among the Rabble: An Intimate History of Gender and Power in the Age of Revolution. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 199.