Longquan celadon (龍泉青瓷) is a type of green-glazed Chinese ceramic, known in the West as celadon or greenware, produced from about 950 to 1550. The kilns were mostly in Lishui prefecture in southwestern Zhejiang Province in the south of China, and the north of Fujian Province. Overall a total of some 500 kilns have been discovered, making the Longquan celadon production area one of the largest historical ceramic producing areas in China. "Longquan-type" is increasingly preferred as a term, in recognition of this diversity, or simply "southern celadon", as there was also a large number of kilns in north China producing Yaozhou ware or other Northern Celadon wares. These are similar in many respects, but with significant differences to Longquan-type celadon, and their production rose and declined somewhat earlier.

Chinese export porcelain includes a wide range of Chinese porcelain that was made (almost) exclusively for export to Europe and later to North America between the 16th and the 20th century. Whether wares made for non-Western markets are covered by the term depends on context. Chinese ceramics made mainly for export go back to the Tang dynasty if not earlier, though initially they may not be regarded as porcelain.

"Blue and white pottery" covers a wide range of white pottery and porcelain decorated under the glaze with a blue pigment, generally cobalt oxide. The decoration is commonly applied by hand, originally by brush painting, but nowadays by stencilling or by transfer-printing, though other methods of application have also been used. The cobalt pigment is one of the very few that can withstand the highest firing temperatures that are required, in particular for porcelain, which partly accounts for its long-lasting popularity. Historically, many other colours required overglaze decoration and then a second firing at a lower temperature to fix that.

Famille jaune, noire, rose, verte are terms used in the West to classify Chinese porcelain of the Qing dynasty by the dominant colour of its enamel palette. These wares were initially grouped under the French names of famille verte, and famille rose by Albert Jacquemart in 1862. The other terms famille jaune (yellow) and famille noire (black) may have been introduced later by dealers or collectors and they are generally considered subcategories of famille verte. Famille verte porcelain was produced mainly during the Kangxi era, while famille rose porcelain was popular in the 18th and 19th century. Much of the Chinese production was Jingdezhen porcelain, and a large proportion were made for export to the West, but some of the finest were made for the Imperial court.

Ding ware, Ting ware or Dingyao are Chinese ceramics, mostly porcelain, that were produced in the prefecture of Dingzhou in Hebei in northern China. The main kilns were at Jiancicun or Jianci in Quyang County. They were produced between the Tang and Yuan dynasties of imperial China, though their finest period was in the 11th century, under the Northern Song. The kilns "were in almost constant operation from the early eighth until the mid-fourteenth century."

Chinese ceramics show a continuous development since pre-dynastic times and are one of the most significant forms of Chinese art and ceramics globally. The first pottery was made during the Palaeolithic era. Chinese ceramics range from construction materials such as bricks and tiles, to hand-built pottery vessels fired in bonfires or kilns, to the sophisticated Chinese porcelain wares made for the imperial court and for export. Porcelain was a Chinese invention and is so identified with China that it is still called "china" in everyday English usage.

Jun ware is a type of Chinese pottery, one of the Five Great Kilns of Song dynasty ceramics. Despite its fame, much about Jun ware remains unclear, and the subject of arguments among experts. Several different types of pottery are covered by the term, produced over several centuries and in several places, during the Northern Song dynasty (960–1127), Jin dynasty (1115–1234) and Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), and lasting into the early Ming dynasty (1368–1644).

Transitional porcelain is Jingdezhen porcelain, manufactured at China’s principle ceramic production area, in the years during and after the transition from Ming to Qing. As with several previous changes of dynasty in China, this was a protracted and painful period of civil war. Though the start date of Qing rule is customarily given as 1644, when the last Ming Emperor hanged himself as the capital fell, the war had really begun in 1618 and Ming resistance continued until 1683. During this period, the Ming system of large-scale manufacturing in the Imperial porcelain factories, with orders and payments coming mainly from the imperial court, finally collapsed, and the officials in charge had to turn themselves from obedient civil servants into businessmen, seeking private customers, including foreign trading companies from Europe, Japanese merchants, and new domestic customers.

Shiwan ware is Chinese pottery from kilns located in the Shiwanzhen Subdistrict of the provincial city of Foshan, near Guangzhou, Guangdong. It forms part of a larger group of wares from the coastal region known collectively as "Canton stonewares". The hilly, wooded, area provided slopes for dragon kilns to run up, and fuel for them, and was near major ports.

Dehua porcelain, more traditionally known in the West as Blanc de Chine, is a type of white Chinese porcelain, made at Dehua in the Fujian province. It has been produced from the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) to the present day. Large quantities arrived in Europe as Chinese export porcelain in the early 18th century and it was copied at Meissen and elsewhere. It was also exported to Japan in large quantities. In 2021, the kilns of Dehua were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List along with many other sites near Quanzhou for their importance for medieval maritime trade and the exchange of cultures and ideas around the world.

Art pottery is a term for pottery with artistic aspirations, made in relatively small quantities, mostly between about 1870 and 1930. Typically, sets of the usual tableware items are excluded from the term; instead the objects produced are mostly decorative vessels such as vases, jugs, bowls and the like which are sold singly. The term originated in the later 19th century, and is usually used only for pottery produced from that period onwards. It tends to be used for ceramics produced in factory conditions, but in relatively small quantities, using skilled workers, with at the least close supervision by a designer or some sort of artistic director. Studio pottery is a step up, supposed to be produced in even smaller quantities, with the hands-on participation of an artist-potter, who often performs all or most of the production stages. But the use of both terms can be elastic. Ceramic art is often a much wider term, covering all pottery that comes within the scope of art history, but "ceramic artist" is often used for hands-on artist potters in studio pottery.

Jingdezhen porcelain is Chinese porcelain produced in or near Jingdezhen in southern China. Jingdezhen may have produced pottery as early as the sixth century CE, though it is named after the reign name of Emperor Zhenzong, in whose reign it became a major kiln site, around 1004. By the 14th century it had become the largest centre of production of Chinese porcelain, which it has remained, increasing its dominance in subsequent centuries. From the Ming period onwards, official kilns in Jingdezhen were controlled by the emperor, making imperial porcelain in large quantity for the court and the emperor to give as gifts.

Cizhou ware or Tz'u-chou ware is a term for a wide range of Chinese ceramics from between the late Tang dynasty and the early Ming dynasty, but especially associated with the Northern Song to Yuan period in the 11–14th century. It has been increasingly realized that a very large number of sites in northern China produced these wares, and their decoration is very variable, but most characteristically uses black and white, in a variety of techniques. For this reason Cizhou-type is often preferred as a general term. All are stoneware in Western terms, and "high-fired" or porcelain in Chinese terms. They were less high-status than other types such as celadons and Jun ware, and are regarded as "popular", though many are finely and carefully decorated.

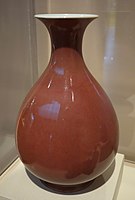

Hugh C. Robertson, (1845–1908), was the first American studio potter who experimented with new ceramic glazes. Born in England, Robertson apprenticed at the Jersey City Potter in 1860. In 1868, he started work in his father's shop that had opened in 1866 in Chelsea, Massachusetts. In 1872 the factory was incorporated into the Chelsea Keramic Art Works (CKAW). The company became known for their antique Grecian terra cotta and Pompeian bronzes. In 1877, Robertson developed the Chelsea faience, underglazed opaque earthenware, which led the development of other American faience. There in 1884, Robertson worked on discovering the famous Chinese sang de boeuf glaze. In 1888, he finally discovered the recipe for the glaze and produced three hundred pieces of what he dubbed, Sang de Chelsea.

Guan ware or Kuan ware is one of the Five Famous Kilns of Song Dynasty China, making high-status stonewares, whose surface decoration relied heavily on crackled glaze, randomly crazed by a network of crack lines in the glaze.

Jizhou ware or Chi-chou ware is Chinese pottery from Jiangxi province in southern China; the Jizhou kilns made a number of different types of wares over the five centuries of production. The best known wares are simple shapes in stoneware, with a strong emphasis on subtle effects in the dark glazes, comparable to Jian ware, but often combined with other decorative effects. In the Song dynasty they achieved a high prestige, especially among Buddhist monks and in relation to tea-drinking. The wares often use leaves or paper cutouts to create resist patterns in the glaze, by leaving parts of the body untouched.

Ge ware or Ko ware is a type of celadon or greenware in Chinese pottery. It was one of the Five Great Kilns of the Song dynasty recognised by later Chinese writers, but has remained rather mysterious to modern scholars, with much debate as to which surviving pieces, if any, actually are Ge ware, whether they actually come from the Song, and where they were made. In recognition of this, many sources call all actual pieces Ge-type ware.

Doucai is a technique in painted Chinese porcelain, where parts of the design, and some outlines of the rest, are painted in underglaze blue, and the piece is then glazed and fired. The rest of the design is then added in overglaze enamels of different colours and the piece fired again at a lower temperature of about 850°C to 900°C.

Wucai is a style of decorating white Chinese porcelain in a limited range of colours. It normally uses underglaze cobalt blue for the design outline and some parts of the images, and overglaze enamels in red, green, and yellow for the rest of the designs. Parts of the design, and some outlines of the rest, are painted in underglaze blue, and the piece is then glazed and fired. The rest of the design is then added in the overglaze enamels of different colours and the piece fired again at a lower temperature of about 850°C to 900°C.

The Macau Scientific and Cultural Centre Museum in Lisbon is Portugal's main museum of Chinese artefacts and artworks. Made to document Sino-Portuguese relations, the museum contains over 3,500 works of art including decorative artwork, costumes, a collection of opium-smoking paraphernalia and an important extensive collection of Chinese ceramics.