Related Research Articles

In poetry, a hendecasyllable is a line of eleven syllables. The term "hendecasyllabic" is used to refer to two different poetic meters, the older of which is quantitative and used chiefly in classical poetry and the newer of which is accentual and used in medieval and modern poetry. The term is often used when a line of iambic pentameter contains 11 syllables.

A strophe is a poetic term originally referring to the first part of the ode in Ancient Greek tragedy, followed by the antistrophe and epode. The term has been extended to also mean a structural division of a poem containing stanzas of varying line length. Strophic poetry is to be contrasted with poems composed line-by-line non-stanzaically, such as Greek epic poems or English blank verse, to which the term stichic applies.

A caesura, also written cæsura and cesura, is a metrical pause or break in a verse where one phrase ends and another phrase begins. It may be expressed by a comma (,), a tick (✓), or two lines, either slashed (//) or upright (||). In time value, this break may vary between the slightest perception of silence all the way up to a full pause.

Ottava rima is a rhyming stanza form of Italian origin. Originally used for long poems on heroic themes, it later came to be popular in the writing of mock-heroic works. Its earliest known use is in the writings of Giovanni Boccaccio.

The Sapphic stanza, named after Sappho, is an Aeolic verse form of four lines. Originally composed in quantitative verse and unrhymed, since the Middle Ages imitations of the form typically feature rhyme and accentual prosody. It is "the longest lived of the Classical lyric strophes in the West".

Syllabic verse is a poetic form having a fixed or constrained number of syllables per line, while stress, quantity, or tone play a distinctly secondary role — or no role at all — in the verse structure. It is common in languages that are syllable-timed, such as French or Finnish — as opposed to stress-timed languages such as English, in which accentual verse and accentual-syllabic verse are more common.

Accentual verse has a fixed number of stresses per line regardless of the number of syllables that are present. It is common in languages that are stress-timed, such as English, as opposed to syllabic verse which is common in syllable-timed languages, such as French.

The Alcaic stanza is a Greek lyrical meter, an Aeolic verse form traditionally believed to have been invented by Alcaeus, a lyric poet from Mytilene on the island of Lesbos, about 600 BC. The Alcaic stanza and the Sapphic stanza named for Alcaeus' contemporary, Sappho, are two important forms of Classical poetry. The Alcaic stanza consists of two Alcaic hendecasyllables, followed by an Alcaic enneasyllable and an Alcaic decasyllable.

Polish poetry has a centuries-old history, similar to the Polish literature.

Aeolic verse is a classification of Ancient Greek lyric poetry referring to the distinct verse forms characteristic of the two great poets of Archaic Lesbos, Sappho and Alcaeus, who composed in their native Aeolic dialect. These verse forms were taken up and developed by later Greek and Roman poets and some modern European poets.

Sappho 31 is an archaic Greek lyric poem by the ancient Greek poet Sappho of the island of Lesbos. The poem is also known as phainetai moi after the opening words of its first line. It is one of Sappho's most famous poems, describing her love for a young woman.

Sappho 16 is a fragment of a poem by the archaic Greek lyric poet Sappho. It is from Book I of the Alexandrian edition of Sappho's poetry, and is known from a second-century papyrus discovered at Oxyrhynchus in Egypt at the beginning of the twentieth century. Sappho 16 is a love poem – the genre for which Sappho was best known – which praises the beauty of the narrator's beloved, Anactoria, and expresses the speaker's desire for her now that she is absent. It makes the case that the most beautiful thing in the world is whatever one desires, using Helen of Troy's elopement with Paris as a mythological exemplum to support this argument. The poem is at least 20 lines long, though it is uncertain whether the poem ends at line 20 or continues for another stanza.

Felicjan Medard Faleński was a Polish poet, playwright, prosaist and translator.

Polish alexandrine is a common metrical line in Polish poetry. It is similar to the French alexandrine. Each line is composed of thirteen syllables with a caesura after the seventh syllable. The main stresses are placed on the sixth and twelfth syllables. Rhymes are feminine.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 5 6 o o o o o S x | o o o o S x Moja wdzięczna Orszulo, bodaj ty mnie była S=stressed syllable; x=unstressed syllable; o=any syllable.

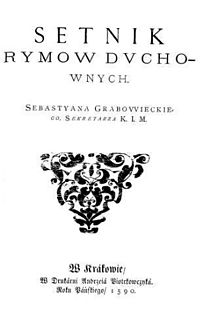

Sebastian Grabowiecki was a Polish Catholic priest and poet. He was the author of Setnik rymów duchownych and Setnik rymów duchownych wtóry. His work, focused entirely on religious themes, was strongly influenced by Italian poetry, especially by Rime Spirituali by Gabriele Fiamma. One of the founding fathers of Polish lyric poetry, Grabowiecki was one of the first poets to write sonnets in Polish. Thus he holds a position comparable to Thomas Wyatt, Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey and Portuguese poet Francisco de Sá de Miranda, who introduced the sonnet into their native literatures. He also wrote the first Polish poem in ottava rima, and was an early adopter of the Sapphic stanza in Polish poetry. His best-known poem is a sonnet similar to Philip Sidney's Sonnet 89 from Astrophel and Stella, with the use of epistrophe instead of rhyme.

Olbrycht Karmanowski was a Polish nobleman, member of Polish Brethren Church, courtier, poet and translator. He is regarded as one of the minor poets of Polish late Renaissance and Baroque.

Sappho 94, sometimes known as Sappho's Confession, is a fragment of a poem by the archaic Greek poet Sappho. The poem is written as a conversation between Sappho and a woman who is leaving her, perhaps in order to marry, and describes a series of memories of their time together. It survives on a sixth-century AD scrap of parchment. Scholarship on the poem has focused on whether the initial surviving lines of the poem are spoken by Sappho or the departing woman, and on the interpretation of the eighth stanza, possibly the only mention of homosexual activities in the surviving Sapphic corpus.

"Sonnet on the Great Suffering of Jesus Christ" is a poem by the 17th-century Polish poet Stanisław Herakliusz Lubomirski. The poem is the last in the sequence The Poems of Lent.

"A Funeral Rhapsody in Memory of General Bem" is a poem by Polish poet Cyprian Norwid, a descendant of the Polish king John III Sobieski. It is an elegy for a famous Polish commander, Józef Bem, who was a hero of three nations, Polish, Hungarian and Turkish. It was written in 1851. The poem is a description of an imaginary funeral. It is described as a funeral of a medieval knight or Slavic warrior, encased in armour, with his horse and a falcon, accompanied by groups of boys and girls. The poem is especially interesting because of its form. It was written in rhymed hexameter. All the lines are made up of fifteen (7+8) syllables according to the pattern ' x ' x x ' x || ' x x ' x x ' x.

Sappho 2 is a fragment of a poem by the archaic Greek lyric poet Sappho. In antiquity it was part of Book I of the Alexandrian edition of Sappho's poetry. Sixteen lines of the poem survive, preserved on a potsherd discovered in Egypt and first published in 1937 by Medea Norsa. It is in the form of a hymn to the goddess Aphrodite, summoning her to appear in a temple in an apple grove. The majority of the poem is made up of an extended description of the sacred grove to which Aphrodite is being summoned.

References

- ↑ Michał Głowiński, Teresa Kostkiewiczowa, Aleksandra Okopień-Sławińska, Janusz Sławiński, Słownik terminów literackich, Wrocław 2002 (polonik).

- ↑ Andrzej Borowski wrote a monograph about Polish literature of 16th century: Andrzej Borowski, Renesans, Wydanie pierwsze, Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagodgiczne, Warszawa 1992.

- ↑ Jan Kochanowski, Tren XVI at Staropolska.pl

- ↑ "Flis to jest spuszczanie statków Wisłą/Tekst poematu - Wikiźródła, wolna biblioteka". Pl.wikisource.org (in Polish). Retrieved 2016-12-31.

- ↑ Tobiasz Wiszniowski, Treny. Opracował Jacek Wóycicki, Wydawnictwo Neriton, Warszawa 2008.

- ↑ See: Treny na śmierć ksiecia Radziwiłła, kasztelana wileńskiego. Tren I [in:] Daniel Naborowski, Poezje wybrane. Wyboru dokonał i opracował Krzysztof Karasek, Ludowa Spółdzielnia Wydawnicza, Warszawa 1980, p. 118-119.

- ↑ Lucylla Pszczołowska, Wiersz polski. Zarys historyczny, Wrocław 1997, p. 115.

- ↑ Lucylla Pszczołowska, Wiersz polski. Zarys historyczny, Wrocław 1997, p. 111.

- ↑ See: Klemens Bolesławiusz, Przeraźliwe echo trąby ostatecznej. Wydał Jacek Sokolski, Instytut Badań Literackich, Warszawa 2004.

- ↑ "Pieśń doroczna na dzień ocalenia życia i zdrowia J. K. Mości - Wikiźródła, wolna biblioteka". Pl.wikisource.org. Retrieved 2016-12-31.

- ↑ "Piesek - Wikiźródła, wolna biblioteka". Pl.wikisource.org (in Polish). 2016-12-02. Retrieved 2016-12-31.

- ↑ Lucylla Pszczołowska, Wiersz polski. Zarys historyczny, Wrocław 1997, p.157.

- 1 2 Lucylla Pszczołowska, Wiersz polski. Zarys historyczny, Wrocław 1997, p. 157.

- ↑ "Gorzkie Żale - tekst - Parafia św Wojciecha w Nasielsku". Wojciech-nasielsk.plock.opoka.org.pl. Retrieved 2016-12-31.

- 1 2 Lucylla Pszczołowska, Wiersz polski. Zarys historyczny, Wrocław 1997, p. 222.

- ↑ "Cyprian Norwid: Wiersze wybrane". Literat.ug.edu.pl. Retrieved 2017-01-05.

- ↑ Lucylla Pszczołowska, Wiersz polski. Zarys historyczny, Wrocław 1997, p. 223.

- ↑ "Cyprian Norwid: Wiersze wybrane". Literat.ug.edu.pl. Retrieved 2017-01-05.

- ↑ "Cyprian Norwid: Wiersze wybrane". Literat.ug.edu.pl. Retrieved 2017-01-05.

- ↑ Kazimierz Wóycicki, Forma dźwiękowa prozy polskiej i wiersza polskiego, E. Wende i S-ka, Warszawa 1912, p. 211.

- ↑ "Antologia wspolczesnych poetow polskich". Archive.org. 2010-07-21. Retrieved 2016-12-31.

- ↑ Lucylla Pszczołowska, Wiersz polski. Zarys historyczny, Wrocław 1997, p. 287.

- ↑ Lucylla Pszczołowska, Wiersz polski. Zarys historyczny, Wrocław 1997, p. 329.

- ↑ Lucylla Pszczołowska, Wiersz polski. Zarys historyczny, Wrocław 1997, p. 64.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2003-12-12. Retrieved 2004-08-31.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Wiktor Jarosław Darasz, Mały przewodnik po wierszu polskim, Towarzystwo Miłośników Języka Polskiego, Kraków 2003, p. 145-146.

- ↑ "Hymn (Smutno mi, Boże...) - Wikiźródła, wolna biblioteka". Pl.wikisource.org (in Polish). 2016-12-11. Retrieved 2016-12-31.

- ↑ Poets and poetry of Poland; a collection of Polish verse, including a short account of the history of Polish poetry, with sixty biographical sketches of Poland's poets and specimens of their composition translated into the English Language by Paul Soboleski, Chicago, 1881, p. 280-282.

- ↑ Lucylla Pszczołowska, Wiersz polski. Zarys historyczny, Wrocław 1997, p. 262.

- ↑ Lucylla Pszczołowska, Wiersz polski. Zarys historyczny, Wrocław 1997, p. 191.