A spear is a polearm consisting of a shaft, usually of wood, with a pointed head. The head may be simply the sharpened end of the shaft itself, as is the case with fire hardened spears, or it may be made of a more durable material fastened to the shaft, such as bone, flint, obsidian, copper, bronze, iron, or steel. The most common design for hunting and/or warfare, since ancient times has incorporated a metal spearhead shaped like a triangle, diamond, or leaf. The heads of fishing spears usually feature multiple sharp points, with or without barbs.

The Battle of Bannockburn was fought on 23–24 June 1314, between the army of Robert the Bruce, King of Scots, and the army of King Edward II of England, during the First War of Scottish Independence. It was a decisive victory for Robert Bruce and formed a major turning point in the war, which ended 14 years later with the de jure restoration of Scottish independence under the Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton. For this reason, the Battle of Bannockburn is widely considered a landmark moment in Scottish history.

Combined arms is an approach to warfare that seeks to integrate different combat arms of a military to achieve mutually complementary effects—for example, using infantry and armour in an urban environment in which each supports the other.

A pike is a long thrusting spear formerly used in European warfare from the Late Middle Ages and most of the early modern period, and wielded by foot soldiers deployed in pike square formation, until it was largely replaced by bayonet-equipped muskets. The pike was particularly well known as the primary weapon of Spanish tercios, Swiss mercenary, German Landsknecht units and French sans-culottes. A similar weapon, the sarissa, had been used in antiquity by Alexander the Great's Macedonian phalanx infantry.

The Battle of the Golden Spurs or 1302 Battle of Courtrai was a military confrontation between the royal army of France and rebellious forces of the County of Flanders on 11 July 1302 during the 1297–1305 Franco-Flemish War. It took place near the town of Kortrijk in modern-day Belgium and resulted in an unexpected victory for the Flemish.

The Battle of Falkirk, on 22 July 1298, was one of the major battles in the First War of Scottish Independence. Led by King Edward I of England, the English army defeated the Scots, led by William Wallace. Shortly after the battle Wallace resigned as Guardian of Scotland.

The sarissa or sarisa was a long spear or pike about 5 to 7 meters in length. It was introduced by Philip II of Macedon and was used in his Macedonian phalanxes as a replacement for the earlier dory, which was considerably shorter. These longer spears improved the strength of the phalanx by extending the rows of overlapping weapons projecting towards the enemy. After the conquests of Alexander the Great, the sarissa was a mainstay during the Hellenistic era by the Hellenistic armies of the diadochi Greek successor states of Alexander's empire, as well as some of their rivals.

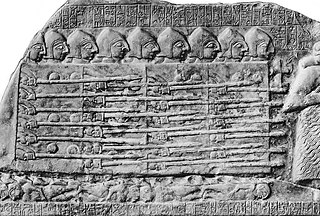

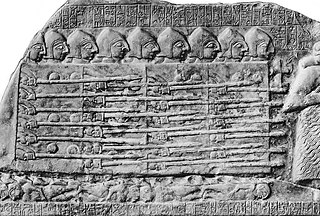

The phalanx was a rectangular mass military formation, usually composed entirely of heavy infantry armed with spears, pikes, sarissas, or similar polearms tightly packed together. The term is particularly used to describe the use of this formation in ancient Greek warfare, although the ancient Greek writers used it to also describe any massed infantry formation, regardless of its equipment. Arrian uses the term in his Array against the Alans when he refers to his legions. In Greek texts, the phalanx may be deployed for battle, on the march, or even camped, thus describing the mass of infantry or cavalry that would deploy in line during battle. They marched forward as one entity.

The pike square was a military tactical formation in which 10 rows of men in 10 columns wielded pikes. It was developed by the Swiss Confederacy during the 14th century for use by its infantry.

A shield wall is a military formation that was common in ancient and medieval warfare. There were many slight variations of this formation, but the common factor was soldiers standing shoulder to shoulder and holding their shields so that they would abut or overlap. Each soldier thus benefited from the protection of the shields of his neighbors and his own.

The Kingdom of Macedon possessed one of the greatest armies in the ancient world. It is reputed for the speed and efficiency with which it emerged from Greece to conquer large swathes of territory stretching from Egypt in the west to India in the east. Initially of little account in the Greek world, it was widely regarded as a second-rate power before being made formidable by Philip II, whose son and successor Alexander the Great conquered the Achaemenid Empire in just over a decade's time.

A pitched battle or set-piece battle is a battle in which opposing forces each anticipate the setting of the battle, and each chooses to commit to it. Either side may have the option to disengage before the battle starts or shortly thereafter. A pitched battle is not a chance encounter such as a meeting engagement, or where one side is forced to fight at a time not of its choosing such as happens in a siege or an ambush. Pitched battles are usually carefully planned to maximize one's strengths against an opponent's weaknesses and use a full range of deceptions, feints, and other manoeuvres. They are also planned to take advantage of terrain favourable to one's force. Forces strong in cavalry, for example, will not select swamp, forest, or mountain terrain for the planned struggle. For example, Carthaginian General Hannibal selected relatively flat ground near the village of Cannae for his great confrontation with the Romans, not the rocky terrain of the high Apennines. Likewise, Zulu Commander Shaka avoided forested areas or swamps, in favour of rolling grassland, where the encircling horns of the Zulu Impi could manoeuvre to effect. Pitched battles continued to evolve throughout history as armies implemented new technology and tactics.

Gaelic warfare was the type of warfare practiced by the Gaelic peoples, in the pre-modern period.

A close order formation is a military tactical formation in which soldiers are close together and regularly arranged for the tactical concentration of force. It was used by heavy infantry in ancient warfare, as the basis for shield wall and phalanx tactics, to multiply their effective weight of arms by their weight of numbers. In the Late Middle Ages, Swiss pikemen and German Landsknechts used close order formations that were similar to ancient phalanxes.

For much of history, humans have used some form of cavalry for war and, as a result, cavalry tactics have evolved over time. Tactically, the main advantages of cavalry over infantry were greater mobility, a larger impact, and a higher riding position.

Heavy infantry consisted of heavily armed and armoured infantrymen who were trained to mount frontal assaults and/or anchor the defensive center of a battle line. This differentiated them from light infantry who were relatively mobile and lightly armoured skirmisher troops intended for screening, scouting, and other tactical roles unsuited to soldiers carrying heavier loads. Heavy infantry typically made use of dense battlefield formations, such as shield wall or phalanx, multiplying their effective weight of arms with force concentration.

The Hellenistic armies is a term that refers to the various armies of the successor kingdoms to the Hellenistic period, emerging soon after the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE, when the Macedonian empire was split between his successors, known as the Diadochi.

Despite the rise of knightly cavalry in the 11th century, infantry played an important role throughout the Middle Ages on both the battlefield and in sieges. From the 14th century onwards, it has been argued that there was a rise in the prominence of infantry forces, sometimes referred to as an "infantry revolution", but this view is strongly contested by some military historians.

The phoulkon, in Latin fulcum, was an infantry formation utilized by the military of the late Roman and Byzantine Empire. It is a formation in which an infantry formation closes ranks and the first two or three lines form a shield wall while those behind them hurl projectiles. It was used in both offensive and defensive stances.

The Macedonian phalanx was an infantry formation developed by Philip II from the classical Greek phalanx, of which the main innovation was the use of the sarissa, a 6-metre pike. It was famously commanded by Philip's son Alexander the Great during his conquest of the Achaemenid Empire between 334 and 323 BC. The Macedonian phalanx model then spread throughout the Hellenistic world, where it became the standard battle formation for pitched battles. During the Macedonian Wars against the Roman Republic, the phalanx appeared obsolete against the more manoeuvrable Roman legions.