Related Research Articles

Within Christianity, there are a variety of views on sexual orientation and homosexuality. The view that various Bible passages speak of homosexuality as immoral or sinful emerged in the first millennium AD, and has since become entrenched in many Christian denominations through church doctrine and the wording of various translations of the Bible.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) movements are social movements that advocate for LGBT people in society. Although there is not a primary or an overarching central organization that represents all LGBT people and their interests, numerous LGBT rights organizations are active worldwide. The first organization to promote LGBT rights was the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, founded in 1897 in Berlin.

The relationship between religion and homosexuality has varied greatly across time and place, within and between different religions and denominations, with regard to different forms of homosexuality and bisexuality. The present-day doctrines of the world's major religions and their denominations differ in their attitudes toward these sexual orientations. Adherence to anti-gay religious beliefs and communities is correlated with the prevalence of emotional distress and suicidality in sexual minority individuals, and is a primary motivation for seeking conversion therapy.

The views of the various different religions and religious believers regarding human sexuality range widely among and within them, from giving sex and sexuality a rather negative connotation to believing that sex is the highest expression of the divine. Some religions distinguish between human sexual activities that are practised for biological reproduction and those practised only for sexual pleasure in evaluating relative morality.

"Gay agenda" or "homosexual agenda" is a term used by sectors of the Christian religious right as a disparaging way to describe the advocacy of cultural acceptance and normalization of non-heterosexual sexual orientations and relationships. The term originated among social conservatives in the United States and has been adopted in nations with active anti-LGBT movements such as Hungary and Uganda.

Homosexuality in Haitian Vodou is religiously acceptable and homosexuals are allowed to participate in all religious activities. However, in West African countries with major conservative Christian and Islamic views on LGBTQ people, the attitudes towards them may be less tolerant if not openly hostile and these influences are reflected in African diaspora religions following Atlantic slave trade which includes Haitian Vodou.

Unitarian Universalism, as practiced by the Unitarian Universalist Association (UUA), and the Canadian Unitarian Council (CUC), is a non-Creedal and Liberal theological tradition and an LGBTQ affirming denomination.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ+)-affirming religious groups are religious groups that welcome LGBT people as their members, do not consider homosexuality as a sin or negative, and affirm LGBT rights and relationships. They include entire religious denominations, as well as individual congregations and places of worship. Some groups are mainly composed of non-LGBTQ+ members and they also have specific programs to welcome LGBTQ+ people into them, while other groups are mainly composed of LGBTQ+ members.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Uganda face severe challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Both male and female forms of same-sex sexual activity are illegal in Uganda. Originally criminalised by British colonial laws introduced when Uganda became a British protectorate, these have been retained since the country gained its independence.

Methodist viewpoints concerning homosexuality are diverse because there is no one denomination which represents all Methodists. The World Methodist Council, which represents most Methodist denominations, has no official statements regarding sexuality. British Methodism holds a variety of views, and permits ministers to bless same-gender marriages. United Methodism, which covers the United States, the Philippines, parts of Africa, and parts of Europe, concentrates on the position that the same-sex relations are incompatible with "Christian teaching", but extends ministry to persons of a homosexual orientation, holding that all individuals are of sacred worth.

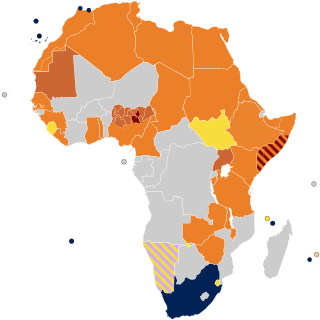

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Africa are generally limited in comparison to the Americas, Western Europe and Oceania.

Many views are held or have been expressed by religious organisation in relation to same-sex marriage. Arguments both in favor of and in opposition to same-sex marriage are often made on religious grounds and/or formulated in terms of religious doctrine. Although many of the world's religions are opposed to same-sex marriage, the number of religious denominations that are conducting same-sex marriages have been increasing since 2010. Religious views on same-sex marriage are closely related to religious views on homosexuality.

Christian denominations have a variety of beliefs about sexual orientation, including beliefs about same-sex sexual practices and asexuality. Denominations differ in the way they treat lesbian, bisexual, and gay people; variously, such people may be barred from membership, accepted as laity, or ordained as clergy, depending on the denomination. As asexuality is relatively new to public discourse, few Christian denominations discuss it. Asexuality may be considered the lack of a sexual orientation, or one of the four variations thereof, alongside heterosexuality, homosexuality, bisexuality, and pansexuality.

The relationship between religion and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people can vary greatly across time and place, within and between different religions and sects, and regarding different forms of homosexuality, bisexuality, non-binary, and transgender identities. More generally, the relationship between religion and sexuality ranges widely among and within them, from giving sex and sexuality a rather negative connotation to believing that sex is the highest expression of the divine.

The Anti-Homosexuality Act, 2014 was an act passed by the Parliament of Uganda on 20 December 2013, which prohibited sexual relations between persons of the same sex. The act was previously called the "Kill the Gays bill" in the western mainstream media due to death penalty clauses proposed in the original version, but the penalty was later amended to life imprisonment. The bill was signed into law by the President of Uganda Yoweri Museveni on 24 February 2014. On 1 August 2014, however, the Constitutional Court of Uganda ruled the act invalid on procedural grounds.

Uganda has a very long and, quite permissive, and sometimes violent history regarding the LGBT community, stretching back from the pre-colonial period, through British colonial control, and even after independence.

Kapya John Kaoma is a Zambian, US-educated scholar, pastor and human rights activist who is most noted for his pro-LGBTQ+ activism, particularly regarding Africa.

Family Watch International (FWI) is a fundamentalist Christian lobbying organization. Founded in 1999, the organization opposes homosexuality, legal abortion, birth control, comprehensive sex education, and other things that it regards as threats to the divinely ordained "natural family." It has a strong presence in Africa, where it promotes conservative policy and attitudes about sexuality through its United Nations (UN) consultative status.

Some or all sexual acts between men, and less frequently between women, have been classified as a criminal offense in various regions. Most of the time, such laws are unenforced with regard to consensual same-sex conduct, but they nevertheless contribute to police harassment, stigmatization, and violence against homosexual and bisexual people. Other effects include exacerbation of the HIV epidemic due to the criminalization of men who have sex with men, discouraging them from seeking preventative care or treatment for HIV infection.

References

- ↑ ‘Homophobic Africa? Toward A More Nuanced View’, African Studies Review, Patrick Awondo, Peter Geschiere and Graeme Ried, Vol. 55.3 (Decemeber 2012), 145.

- ↑ African Studies Review, 147

- ↑ Are same-sex marriages un-African?’ 338.

- ↑ ‘“Homosexuality” in Africa: Issues and Debates’, Issue: A Journal of Opinion, Vol.25.1, Commentaries in African Studies: Essays about African Social Change and the Meaning of Our Professional Work (1997), 8.

- ↑ “Homosexuality” in Africa, 8.

- ↑ ‘Are Same-Sex Marriages UnAfrican? Same-Sex Relationships and Belonging in Post-Apartheid South Africa’, Mikki van Zyl, in Journal of Social Issues, 2011-06, vol.67.2, (USA: Blackwell Publishing Inc).

- ↑ ‘Reviewed Works: Human Rights and Homosexuality in Southern Africa by Chris Dunton and Mai Palmberg; Beset by Contradictions: Islamization, Legal Reform and Human Rights in Sudan by Lawyers' Committee for Human Rights’, Review by: Rhonda Howard, African Studies Review, Vol 41.1 (April, 1998), 190-191.

- ↑ ‘Are same-sex marriages un-African?’, vol 67.2.

- ↑ ‘Black lesbian women in South Africa: Citizenship and the Coloniality of Power’ Angeline Stephens AND Floretta Boonzaier, Feminism & Pyschology, 2020-08. Vol 30.3, 325.

- ↑ ‘‘Queer/white’ in South Africa A Troubling Oxymoron?’ in Queer in Africa: LGBTQ identities, citizenship, and activism, Jane Bennett e.d. by Vasu Reddy and Surya Monro, (New York: Routledge, 2018), 109.

- ↑ ‘Black lesbian women in South Africa’, 327.

- ↑ ‘Sexuality and nationalist ideologies in post-colonial Cameroon’ Basile Ndjio, in The Sexual History of the Global South: Sexual Politics in Africa, Asia and Latin America, ed, Saskia Wieringa and Horacio Sivori, (England, London: Zed Books, 2013), 128.

- ↑ ‘Sexuality and Nationalist Ideologies in Post-Colonial Cameroon’, 136.

- ↑ Caldwell, John C., and Pat Caldwell. "The cultural context of high fertility in sub-Saharan Africa." Population and development review (1987): 409-437.

- ↑ Helleve, Arnfinn, et al. "South African teachers' reflections on the impact of culture on their teaching of sexuality and HIV/AIDS." Culture, health & sexuality 11.2 (2009): 189-204.

- ↑ Njambi, Wairimũ Ngaruiya. "Dualisms and female bodies in representations of African female circumcision A feminist critique." Feminist Theory 5.3 (2004): 281-303.

- ↑ Fanusie, Lloyda. "Sexuality and women in African culture." The Will to Arise: Women, Tradition and the Church in Africa (1992): 135-154.

- ↑ "More women than men have added their DNA to the human gene pool". TheGuardian.com . 24 September 2014.

- ↑ Mawerenga Jones Hamburu, The Homosexuality Debate in Malawi, (Baltimore: Project Muse, 2018), pg. 178

- ↑ Kaoma Kapya, ‘The Interaction of Human Rights and Religion in Africa’s Sexuality Politics’, International Journal of Constitutional Law, Vol, 21 (1), (2023), 339-355, pg. 341

- ↑ Kaoma Kapya, ‘The Interaction of Human Rights and Religion in Africa’s Sexuality Politics’, International Journal of Constitutional Law, Vol, 21 (1), (2023), 339-355, pg. 346

- ↑ Mawerenga Jones Hamburu, The Homosexuality Debate in Malawi, (Baltimore: Project Muse, 2018, pg. 165

- ↑ Mawerenga Jones Hamburu, The Homosexuality Debate in Malawi, (Baltimore: Project Muse, 2018, pg. 166

- ↑ Mawerenga Jones Hamburu, The Homosexuality Debate in Malawi, (Baltimore: Project Muse, 2018, pg. 176

- ↑ Mawerenga Jones Hamburu, The Homosexuality Debate in Malawi, (Baltimore: Project Muse, 2018, pg. 176

- ↑ Mawerenga Jones Hamburu, The Homosexuality Debate in Malawi, (Baltimore: Project Muse, 2018, pg. 176

- ↑ Mawerenga Jones Hamburu, The Homosexuality Debate in Malawi, (Baltimore: Project Muse, 2018, pg. 178

- ↑ Thabo Msibi, ‘The Lies We Have Been Told: On (Homo) Sexuality in Africa’, Africa Today, 58.1 (2011), p . 57. <https://doi.org/10.2979/africatoday.58.1.55>.

- ↑ Thabo Msibi, ‘The Lies We Have Been Told: On (Homo) Sexuality in Africa’, Africa Today, 58.1 (2011), p . 59. <https://doi.org/10.2979/africatoday.58.1.55>.

- ↑ Deborah Kintu, The Ugandan Morality Crusade (McFarland, 2017). Ch 4 p . 70.

- ↑ Kapya Kaoma, ‘The Interaction of Human Rights and Religion in Africa’s Sexuality Politics’, International Journal of Constitutional Law, 21.1 (2023) p . 340. <https://doi.org/10.1093/icon/moad031>.

- ↑ Deborah Kintu, The Ugandan Morality Crusade (McFarland, 2017). Ch 2 p . 24.

- ↑ Deborah Kintu, The Ugandan Morality Crusade (McFarland, 2017). Ch 3 p . 43.