| Sharkey Landfill | |

|---|---|

| Superfund site | |

| Geography | |

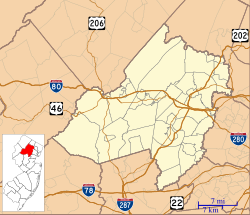

| City | Parsippany |

| County | Morris |

| State | New Jersey |

| Coordinates | 40°50′52″N74°20′53″W / 40.847660°N 74.348186°W |

| Information | |

| CERCLIS ID | NJD980505762 |

| Contaminants | 2-Methylnaphthalene, butanone, acetone, polychlorinated biphenyl, barium, cadmium, Chlorobenzene, chromium, cyanide |

| Responsible parties | Ciba-Geigy |

| Progress | |

| Proposed | December 30, 1982 |

| Listed | September 8, 1983 |

| Construction completed | March 9, 2004 |

| List of Superfund sites | |

Sharkey Landfill is a 90-acre property located in New Jersey along the Rockaway and Whippany rivers in Parsippany, New Jersey. Landfill operations began in 1945, and continued until September 1972, when large amounts of toluene, benzene, chloroform, dichloroethylene, and methylene chloride were found, all of which have are a hazard to human health causing cancer and organ failure. Sharkey Landfill was put on the National Priority List (or NPL) in 1983, and clean up operations ran until the site was deemed as not a threat in 2004. [1]

Contents

- Origins

- Town history

- Company history

- Superfund designation

- State intervention

- National intervention

- Health and environmental hazards

- Hazard 1: toluene

- Hazard 2: benzene

- Hazard 3: chloroform

- Hazard 4: methylene chloride

- Hazard 5: dichloroethylene

- Clean up

- Initial clean up

- Current status

- See also

- References

- External links