Related Research Articles

Shantideva was an 8th-century CE Indian philosopher, Buddhist monk, poet, and scholar at the mahavihara of Nalanda. He was an adherent of the Mādhyamaka philosophy of Nāgārjuna.

Sonam Gyatso was the first to be named Dalai Lama, although the title was retrospectively given to his two predecessors.

The Gelug is the newest of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism. It was founded by Je Tsongkhapa (1357–1419), a Tibetan philosopher, tantric yogi and lama and further expanded and developed by his disciples.

The Jonang is a school of Indo-Tibetan Buddhism. Its origins in Tibet can be traced to the early 12th century master Yumo Mikyo Dorje. It became widely known through the work of the popular 14th century figure Dolpopa Sherab Gyaltsen. The Jonang school's main practice is the Kālacakra tantra, and they are widely known for their defense of the philosophy known as shentong.

Altan Khan of the Tümed, whose given name was Anda, was the leader of the Tümed Mongols de facto ruler of the Right Wing, or western tribes, of the Mongols, and the first Ming Shunyi King (顺义王). He was the grandson of Dayan Khan (1464–1543), a descendant of Kublai Khan (1215–1294), who had managed to unite a tribal league between the Khalkha Mongols in the north and the Chahars (Tsakhars) to the south. His name means "Golden Khan" in the Mongolian language.

Buddhist music is music created for or inspired by Buddhism and includes numerous ritual and non-ritual musical forms. As a Buddhist art form, music has been used by Buddhists since the time of early Buddhism, as attested by artistic depictions in Indian sites like Sanchi. While certain early Buddhist sources contain negative attitudes to music, Mahayana sources tend to be much more positive to music, seeing it as a suitable offering to the Buddhas and as a skillful means to bring sentient beings to Buddhism.

The history of Buddhism can be traced back to the 5th century BCE. Buddhism arose in Ancient India, in and around the ancient Kingdom of Magadha, and is based on the teachings of the renunciate Siddhārtha Gautama. The religion evolved as it spread from the northeastern region of the Indian subcontinent throughout Central, East, and Southeast Asia. At one time or another, it influenced most of Asia.

Buddhism in Nepal started spreading since the reign of Ashoka through Indian and Tibetan missionaries. The Kiratas were the first people in Nepal who embraced Gautama Buddha’s teachings, followed by the Licchavis and Newar people. Shakyamuni Buddha was born in Lumbini in the Shakya Kingdom. Besides Shakyamuni Buddha, there are many Buddha(s) before him who are worshipped in different parts of Nepal. Lumbini lies in present-day Rupandehi District, Lumbini zone of Nepal. Buddhism is the second-largest religion in Nepal. According to 2001 census, 10.74% of Nepal's population practiced Buddhism, consisting mainly of Tibeto-Burman-speaking ethnicities and the Newar. However, in the 2011 census, Buddhists made up just 9% of the country's population.

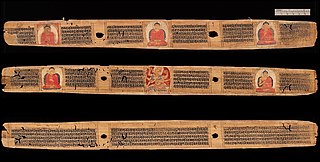

Dharanis, also known as Parittas, are Buddhist chants, mnemonic codes, incantations, or recitations, usually the mantras consisting of Sanskrit or Pali phrases. Believed to be protective and with powers to generate merit for the Buddhist devotee, they constitute a major part of historic Buddhist literature. Many of these chants are in Sanskrit and Pali, written in scripts such as Siddhaṃ as well as transliterated into Chinese, Korean, Japanese, Vietnamese, Sinhala, Thai and other regional scripts. They are similar to and reflect a continuity of the Vedic chants and mantras.

The Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta is a Buddhist scripture that is considered by Buddhists to be a record of the first sermon given by Gautama Buddha, the Sermon in the Deer Park at Sarnath. The main topic of this sutta is the Four Noble Truths, which refer to and express the basic orientation of Buddhism in a formulaic expression. This sutta also refers to the Buddhist concepts of the Middle Way, impermanence, and dependent origination.

Sakya PanditaKunga Gyeltsen was a Tibetan spiritual leader and Buddhist scholar and the fourth of the Five Sakya Forefathers. Künga Gyeltsen is generally known simply as Sakya Pandita, a title given to him in recognition of his scholarly achievements and knowledge of Sanskrit. He is held in the tradition to have been an emanation of Manjusri, the embodiment of the wisdom of all the Buddhas.

Newar Buddhism is the form of Vajrayana Buddhism practiced by the Newar people of the Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. It has developed unique socio-religious elements, which include a non-monastic Buddhist society based on the Newar caste system and patrilineality. The ritual priestly (guruju) caste, vajracharya and shakya form the non-celibate religious clergy caste while other Buddhist Newar castes like the Urāy act as patrons. Uray also patronise Tibetan Vajrayana, Theravadin, and even Japanese clerics. It is the oldest known sect of the Vajrayana tradition outdating the Tibetan school of Vajrayana by more than 600 years.

Glenn H. Mullin is a Tibetologist, Buddhist writer, translator of classical Tibetan literature and teacher of Tantric Buddhist meditation.

Kumbum Monastery, also called Ta'er Temple, is a Tibetan gompa in Lusar, Huangzhong County, Xining, Qinghai, China. It was founded in 1583 in a narrow valley close to the village of Lusar in the historical Tibetan region of Amdo. Its superior monastery is Drepung Monastery, immediately to the west of Lhasa. It is ranked in importance as second only to Lhasa.

Indonesian Esoteric Buddhism or Esoteric Buddhism in Maritime Southeast Asia refers to the traditions of Esoteric Buddhism found in Maritime Southeast Asia which emerged in the 7th century along the maritime trade routes and port cities of the Indonesian islands of Java and Sumatra as well as in Malaysia. These esoteric forms were spread by pilgrims and Tantric masters who received royal patronage from royal dynasties like the Sailendras and the Srivijaya. This tradition was also linked by the maritime trade routes with Indian Vajrayana, Tantric Buddhism in Sinhala, Cham and Khmer lands and in China and Japan, to the extent that it is hard to separate them completely and it is better to speak of a complex of "Esoteric Buddhism of Mediaeval Maritime Asia." Many key Indian port cities saw the growth of Esoteric Buddhism, a tradition which coexisted alongside Shaivism.

The Samādhirāja Sūtra or Candrapradīpa Sūtra is a Buddhist Mahayana sutra. Some scholars have dated its redaction from the 2nd or 3rd century CE to the 6th century, but others argue that its date just cannot be determined. The Samādhirāja is a very important source for the Madhyamaka school and it is cited by numerous Indian authors like Chandrakirti, Shantideva and later Buddhist authors. According to Alex Wayman, the Samādhirāja is "perhaps the most important scriptural source for the Madhyamika." The Samādhirāja is also widely cited in Tantric Buddhist sources, which promote its recitation for ritual purposes. A commentary to the sutra, the Kīrtimala, was composed by the Indian Manjushrikirti and this survives in Tibetan.

Mongolian literature is literature written in Mongolia and/or in the Mongolian language. It was greatly influenced by and evolved from its nomadic oral storytelling traditions, and it originated in the 13th century. The "three peaks" of Mongol literature, The Secret History of the Mongols, Epic of King Gesar and Epic of Jangar, all reflect the age-long tradition of heroic epics on the Eurasian Steppe. Mongol literature has also been a reflection of the society of the given time, its level of political, economic and social development as well as leading intellectual trends.

Chinese Esoteric Buddhism refers to traditions of Tantra and Esoteric Buddhism that have flourished among the Chinese people. The Tantric masters Śubhakarasiṃha, Vajrabodhi and Amoghavajra, established the Esoteric Buddhist Zhenyan tradition from 716 to 720 during the reign of Emperor Xuanzong of Tang. It employed mandalas, mantras, mudras, abhiṣekas, and deity yoga. The Zhenyan tradition was transported to Japan as Shingon Buddhism by Kūkai as well as influencing Korean Buddhism and Vietnamese Buddhism. The Song dynasty (960–1279) saw a second diffusion of Esoteric texts. Esoteric Buddhist practices continued to have an influence into the late imperial period and Tibetan Buddhism was also influential during the Yuan dynasty period and beyond. In the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) through to the modern period, esoteric practices and teachings became absorbed and merged with the other Chinese Buddhist traditions to a large extent.

Buddhists, predominantly from India, first actively disseminated their practices in Tibet from the 6th to the 9th centuries CE. During the Era of Fragmentation, Buddhism waned in Tibet, only to rise again in the 11th century. With the Mongol invasion of Tibet and the establishment of the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) in China, Tibetan Buddhism spread beyond Tibet to Mongolia and China. From the 14th to the 20th centuries, Tibetan Buddhism was patronized by the Chinese Ming dynasty (1368–1644) and the Manchurian Qing dynasty (1644–1912) which ruled China.

Chosgi Odsir (1260–1320) was a Lamaist scholar, writer, translator into Mongolian and Buddhist monk. He was the teacher of Shirab Sengge.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Baumann, Brian (2008). Divine Knowledge Buddhist Mathematics According to the Anonymous Manual of Mongolian Astrology and Divination. Brill. p. 287. ISBN 978-90-474-2836-7.

While the ethnic origins of the translators employed by Mongol patrons is often uncertain (though Shereb Sengge was likely a Mongol) [...]

- 1 2 "Mongolian literature". Britannica. Archived from the original on 18 May 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- 1 2 Laura C. Lambdin; Robert T. Lambdin (2013). Encyclopedia of Medieval Literature. Routledge. pp. 395–396. ISBN 978-1-136-59425-0.

- ↑ Śāntideva (1998). Translator's Note: The Bodhicaryāvatāra. Oxford University Press. p. xxviii. ISBN 978-0-19-283720-2.

- ↑ Baumann, Brian (2008). Divine Knowledge Buddhist Mathematics According to the Anonymous Manual of Mongolian Astrology and Divination. Brill. p. 287. ISBN 978-90-474-2836-7.

- ↑ Brown, Delmer (1993). The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 1: Ancient Japan. Cambridge University Press. p. 393. ISBN 978-0-521-22352-2.

- ↑ Gregory, Peter N.; Getz Jr., Daniel A. (2002). Buddhism in the Sung. University of Hawaii Press. p. 374. ISBN 978-0-8248-2681-9.