Kuala Lumpur, officially the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur, and colloquially referred to as KL, is the capital city and a federal territory of Malaysia. It is the largest city in the country, covering an area of 243 km2 (94 sq mi) with a census population of 2,075,600 as of 2024. Greater Kuala Lumpur, also known as the Klang Valley, is an urban agglomeration of 8.8 million people as of 2024. It is among the fastest growing metropolitan regions in Southeast Asia, both in population and economic development.

Penang is a Malaysian state located on the northwest coast of Peninsular Malaysia along the Strait of Malacca. It has two parts: Penang Island, where the capital city, George Town, is located, and Seberang Perai on the Malay Peninsula. These two halves are physically connected by the Penang Bridge and the Second Penang Bridge. The state shares borders with Kedah to the north and east, and Perak to the south.

Chinatowns in Asia are widespread with large concentrations of overseas Chinese in East Asia and Southeast Asia, and ethnic Chinese whose ancestors came from southern China — particularly the provinces of Guangdong, Fujian, and Hainan — and settled in countries such as Brunei, Cambodia, East Timor, Indonesia, India, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Vietnam, Japan and Korea centuries ago — starting as early as the Tang dynasty, but mostly notably in the 17th–19th centuries, and well into the 20th century. Today the Chinese diaspora in Asia is primarily concentrated in Southeast Asia; however, the legacy of the once widespread overseas Chinese communities in Asia is evident in the many Chinatowns found across East, South and Southeast Asia.

A hawker centre(Chinese: 小贩中心) or cooked food centre(Chinese: 熟食中心) is an often open-air complex commonly found in Hong Kong, Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia. They were built to provide a more sanitary alternative to mobile hawker carts and contain many stalls that sell different varieties of affordable meals. Dedicated tables and chairs are usually provided for diners.

Sogo Co., Ltd. is a department store chain that operates an extensive network of branches in Japan. In 2009, it merged with The Seibu Department Stores, Ltd. (株式会社西武百貨店) to become Sogo & Seibu Co., Ltd. (株式会社そごう・西武). It once owned stores in locations as diverse as Beijing in China, Causeway Bay in Hong Kong, Taipei in Taiwan, Jakarta and Surabaya in Indonesia, Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia, Singapore, Bangkok in Thailand, London in United Kingdom, but most of these international branches are now closed or operated by independent franchisees.

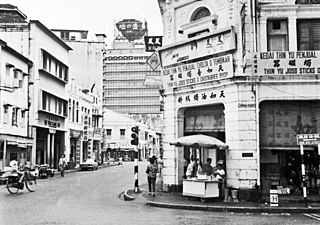

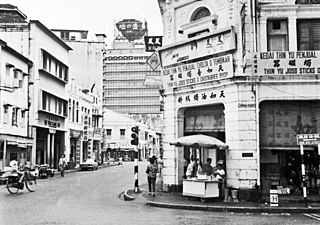

Petaling Street is a Chinatown located in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. The whole vicinity is also known as Chinatown KL. Haggling is a common sight here and the place is usually crowded with locals as well as tourists.

Shanghai Street is a 2.3 km long street in the Jordan, Yau Ma Tei and Mong Kok areas of Kowloon, Hong Kong. Completed in 1887 under the name of Station Street (差館街), it was once the most prosperous street in Kowloon. It originates from the south at Austin Road, and terminates in the north at Lai Chi Kok Road. Parallel to Shanghai Street are Nathan Road, Temple Street, Portland Street, Reclamation Street and Canton Road. Though parallel, Shanghai Street was marked by 2- to 3-floor Chinese-style buildings while Nathan Road was marked by Western-style buildings.

Brickfields is a neighbourhood located on the western flank of central Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. It is known as Kuala Lumpur's Little India due to the high percentage of Indian residents and businesses. Brickfields has been ranked third in Airbnb's list of top trending destinations.

A five-foot way is a roofed continuous walkway commonly found in front of shops in Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia which may also be used for commercial activity. The name refers to the width of the passageway, but a five-foot way may be narrower or wider than 5 feet (1.5 m). Although it looks like European arcade along the streets, it is a building feature that suits the local climate, and characterizes the town-scape and urban life of this region. It may also be found in parts of Thailand, Taiwan, and Southern China. The term might be translated into Hokkien as ngó͘-kha-ki (五脚基); it is also called têng-á-kha (亭子脚).

Methodist Boys' School is an all-boys secondary school in George Town, Penang, Malaysia. It is one of the two secondary schools in George Town that were established by Methodists, the other being Methodist Girls' School.

The architecture of Penang reflects the 171 years of British presence on the island, coalescing with local, Chinese, Indian, Islamic and other elements to create a unique and distinctive brand of architecture. Along with Malacca, Penang is an architectural gem of Malaysia and Southeast Asia. Unlike Singapore, also a Straits Settlement, where many heritage buildings had to make way for modern skyscrapers and high-rise apartments due to rapid development and acute land scarcity, Penang's architectural heritage has enjoyed a better fate. Penang has one of the largest collections of pre-war buildings in Southeast Asia. This is for the most part due to the Rent Control Act which froze house rental prices for decades, making redevelopment unprofitable. With the repeal of this act in 2000 however, property prices skyrocketed and development has begun to encroach upon these buildings, many of which are in a regrettable state of disrepair. The government in recent years has allocated more funding to finance the restoration of a number of derelict heritage buildings, most notably Suffolk House, City Hall and historic buildings in the old commercial district.

Kuala Lumpur is the largest city in Malaysia; it is also the nation's capital. The history of Kuala Lumpur began in the middle of the 19th century with the rise of the tin mining industry, and boomed in the early 20th century with the development of rubber plantations in Selangor. It became the capital of Selangor, later the Federated Malay States, and then Malayan Union, Malaya and finally Malaysia.

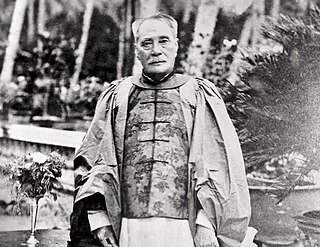

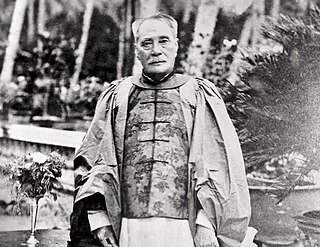

Loke Yew CMG, born Wong Loke Yew, was a Malayan business magnate of Cantonese descent. During his lifetime, he played a significant role in the development of Kuala Lumpur and was also one of the founding fathers of Victoria Institution in Kuala Lumpur.

Swan & Maclaren Group business have expanded beyond Architecture & Urban Design, and presently include Interior Design, Adaptive Reuse, Illumination Engineering, Immersive Experience Design, Sustainability Solutions, and in the near future, Luxury Senior Living development. One of the oldest architectural firms in the country, it was formerly known as Swan & Maclaren and Swan & Lermit, and was one of the most prominent architectural firms in Singapore when it was a crown colony during the early 20th century. The firm has designed numerous iconic heritage buildings in Singapore as well as Malaysia. Presently headquartered in UE Square Singapore, the firm has continued to design numerous projects in contemporary Singapore. Swan & Maclaren Group has operational presence in several countries around Asia, UK and the Middle East.

Tong lau or ke lau are tenement buildings built from the late 19th century to the 1960s in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Southern China, and Southeast Asia. Designed for both residential and commercial uses, they are similar in style and function to the shophouses with five-foot way of Southeast Asia. Over the years, tong lau construction has seen influences of Edwardian-style architecture and later the Bauhaus movement.

Nos. 600–626 Shanghai Street, or more specifically Nos. 600, 602, 604, 606, 612, 614, 620, 622, 624 and 626, is a group of ten pre-war shophouses (tong-lau) in the Mong Kok section of Shanghai Street, in Hong Kong, that have been listed as Grade I historical buildings for their historical value.

SPARK is an international architecture and urban design studio registered in London, Singapore and Shanghai. The studio has designed a variety of projects from complex multiphased mixed-use buildings, city-scale master plans, residential and hotel developments, building regeneration and transformations to small scale urban infill projects.

Arthur Benison Hubback was a British Army officer and architect who designed several important buildings in British Malaya, in both Indo-Saracenic architecture and European "Wrenaissance" styles. Major works credited to him include Kuala Lumpur railway station, Ubudiah Mosque, Jamek Mosque, National Textile Museum, Panggung Bandaraya DBKL, Ipoh railway station, and Kowloon railway station.

Kampung Cina, is a Chinatown located in Kuala Terengganu, Terengganu, Malaysia. Kampung Cina is located along Jalan Bandar, in Kuala Terengganu city centre at the river mouth of Terengganu River that empties into the South China Sea. Kampung Cina literally means Chinese Village; it is also called Tn̂g-lâng-pho (唐人坡) or KT's Chinatown by local people. It is one of Southeast Asia's early Chinese settlements and contains stately ancestral homes, temples, townhouses, and business establishments. The town is small but has colourful shophouses along both sides of the road that carries traditional flavour.

George Town, the capital city of the state of Penang, is the second largest city in Malaysia and the economic centre of the country's northern region. The history of George Town began with its establishment by Captain Francis Light of the British East India Company in 1786. Founded as a free port, George Town became the first British settlement in Southeast Asia and prospered in the 19th century as one of the vital British entrepôts within the region. It briefly became the capital of the Straits Settlements, a British crown colony which also consisted of Singapore and Malacca.