Related Research Articles

The Epipalaeolithic Near East designates the Epipalaeolithic in the prehistory of the Near East. It is the period after the Upper Palaeolithic and before the Neolithic, between approximately 20,000 and 10,000 years Before Present (BP). The people of the Epipalaeolithic were nomadic hunter-gatherers who generally lived in small, seasonal camps rather than permanent villages. They made sophisticated stone tools using microliths—small, finely-produced blades that were hafted in wooden implements. These are the primary artifacts by which archaeologists recognise and classify Epipalaeolithic sites.

Natufian culture is a Late Epipaleolithic archaeological culture of the Neolithic prehistoric Levant in Western Asia, dating to around 15,000 to 11,500 years ago. The culture was unusual in that it supported a sedentary or semi-sedentary population even before the introduction of agriculture. Natufian communities may be the ancestors of the builders of the first Neolithic settlements of the region, which may have been the earliest in the world. Some evidence suggests deliberate cultivation of cereals, specifically rye, by the Natufian culture at Tell Abu Hureyra, the site of earliest evidence of agriculture in the world. The world's oldest known evidence of the production of bread-like foodstuff has been found at Shubayqa 1, a 14,400-year-old site in Jordan's northeastern desert, 4,000 years before the emergence of agriculture in Southwest Asia. In addition, the oldest known evidence of possible beer-brewing, dating to approximately 13,000 BP, was found in Raqefet Cave on Mount Carmel, although the beer-related residues may simply be a result of a spontaneous fermentation.

Stone tools have been used throughout human history but are most closely associated with prehistoric cultures and in particular those of the Stone Age. Stone tools may be made of either ground stone or knapped stone, the latter fashioned by a craftsman called a flintknapper. Stone has been used to make a wide variety of tools throughout history, including arrowheads, spearheads, hand axes, and querns. Knapped stone tools are nearly ubiquitous in pre-metal-using societies because they are easily manufactured, the tool stone raw material is usually plentiful, and they are easy to transport and sharpen.

In archaeology, ground stone is a category of stone tool formed by the grinding of a coarse-grained tool stone, either purposely or incidentally. Ground stone tools are usually made of basalt, rhyolite, granite, or other cryptocrystalline and igneous stones whose coarse structure makes them ideal for grinding other materials, including plants and other stones.

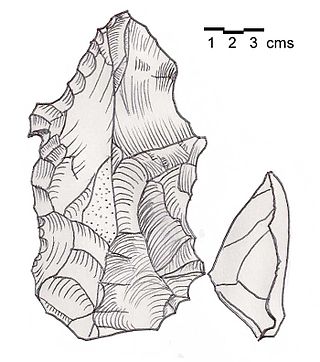

In archaeology, a denticulate tool is a stone tool containing one or more edges that are worked into multiple notched shapes, much like the toothed edge of a saw. Such tools have been used as saws for woodworking, processing meat and hides, craft activities and for agricultural purposes. Denticulate tools were used by many different groups worldwide and have been found at a number of notable archaeological sites. They can be made from a number of different lithic materials, but a large number of denticulate tools are made from flint.

A sickle, bagging hook, reaping-hook or grasshook is a single-handed agricultural tool designed with variously curved blades and typically used for harvesting or reaping grain crops, or cutting succulent forage chiefly for feeding livestock. Falx was a synonym, but was later used to mean any of a number of tools that had a curved blade that was sharp on the inside edge.

The Kebaran culture, also known as the 'Early Near East Epipalaeolithic', is an archaeological culture of the Eastern Mediterranean dating to c. 23,000 to 15,000 Before Present (BP). Its type site is Kebara Cave, south of Haifa. The Kebaran was produced by a highly mobile nomadic population, composed of hunters and gatherers in the Levant and Sinai areas who used microlithic tools.

Mureybet is a tell, or ancient settlement mound, located on the west bank of the Euphrates in Raqqa Governorate, northern Syria. The site was excavated between 1964 and 1974 and has since disappeared under the rising waters of Lake Assad. Mureybet was occupied between 10,200 and 8,000 BC and is the eponymous type site for the Mureybetian culture, a subdivision of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA). In its early stages, Mureybet was a small village occupied by hunter-gatherers. Hunting was important and crops were first gathered and later cultivated, but they remained wild. During its final stages, domesticated animals were also present at the site.

Ohalo II is an archaeological site in Northern Israel, near Kinneret, on the southwest shore of the Sea of Galilee. It is one of the best preserved hunter-gatherer archaeological sites of the Last Glacial Maximum, radiocarbon dated to around 23,000 BP (calibrated). It is at the junction of the Upper Paleolithic and the Epipaleolithic, and has been attributed to both periods. The site is significant for two findings which are the world's oldest: the earliest brushwood dwellings and evidence for the earliest small-scale plant cultivation, some 11,000 years before the onset of agriculture. The numerous fruit and cereal grain remains preserved in anaerobic conditions under silt and water are also exceedingly rare due to their general quick decomposition.

The prehistory of the Levant includes the various cultural changes that occurred, as revealed by archaeological evidence, prior to recorded traditions in the area of the Levant. Archaeological evidence suggests that Homo sapiens and other hominid species originated in Africa and that one of the routes taken to colonize Eurasia was through the Sinai Peninsula desert and the Levant, which means that this is one of the most occupied locations in the history of the Earth. Not only have many cultures lived here, but also many species of the genus Homo. In addition, this region is one of the centers for the development of agriculture.

The Helwan retouch was a bifacial microlithic flint-tool fabrication technology characteristic of the Early Natufian culture in the Levant, a region in the Eastern Mediterranean such as the Harifian culture. The decline of the Helwan Retouch was largely replaced by the "backing" technique and coincided with the emergence of microburin methods, which involved snapping bladelets on an anvil. Natufian lithic technology throughout the usage of the Helwan Retouch was dominated by lunate-shaped lithics, such as picks and axes and especially sickles.

The Nachcharini cave is located at a height of 2,100 m (6,889.76 ft) on the Nachcharini Plateau in the Anti-Lebanon Mountains near the Lebanese/Syrian border and among the most elevated Natufian and Khiamian hunter-gatherer occupation sites found to date.

Avi Gopher is an Israeli archaeologist. He is a professor at the University of Tel Aviv.

Aammiq is a village in the Western Beqaa District in Lebanon. It is also the name of an archaeological site.

The Sands of Beirut were a series of archaeological sites located on the coastline south of Beirut in Lebanon.

Iraq ed-Dubb, or the Cave of the Bear, is an early Neolithic archeological site 7 km (4.3 mi) northwest of Ajlun in the Jordan Valley, in modern-day Jordan. The settlement existed before 8,000 BCE and experimented with the cultivation of founder crops, side by side with the harvesting of wild cereals. Along with Tell Aswad in Syria, the site shows the earliest reference to domestic hulled barley between 10,000 and 8,800 BCE. The site is located on a forested limestone escarpment above the Wadi el-Yabis in northwest Jordan. An oval-shaped stone structure was excavated along with two burials and a variety of animal and plant remains.

Hatula is an early Neolithic archeological site in the Judean hills south of Latrun, beside Nahshon Stream, in Israel, 20 kilometres (12 mi) west of Jerusalem. The site is 15 metres (49 ft) above the riverbed on a rocky slope in an alluvial valley. Excavations revealed three levels of occupation in the Natufian, Khiamian and PPNA (Sultanian).

Heavy Neolithic is a style of large stone and flint tools associated primarily with the Qaraoun culture in the Beqaa Valley, Lebanon, dating to the Epipaleolithic or early Pre-Pottery Neolithic at the end of the Stone Age. The type site for the Qaraoun culture is Qaraoun II.

Anna Belfer-Cohen is an Israeli archaeologist and paleoanthropologist and Professor Emeritus at the Institute of Archaeology, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Belfer-Cohen excavated and studied many important prehistoric sites in Israel including Hayonim and Kebara Caves and open-air sites such as Nahal Ein Gev I and Nahal Neqarot. She has also worked for many years in the Republic of Georgia, where she made important contributions to the study of the Paleolithic sequence of the Caucasus following her work at the cave sites of Dzoudzuana, Kotias and Satsrublia. She is a specialist in biological Anthropology, prehistoric art, lithic technology, the Upper Paleolithic and modern humans, the Natufian-Neolithic interface and the transition to village life.

Ghaba is a Neolithic cemetery mound and African archaeological site located in Central Sudan in the Shendi region of the Nile Valley. The site, discovered in 1977 by the Section Française de la Direction des Antiquités du Soudan (SFDAS) while they were investigating nearby Kadada, dates to 4750–4350 and 4000–3650 cal BC. Archaeology of the site originally heavily emphasized pottery, as there were many intact or mostly intact vessels. Recent analysis has focused on study of plant material found, which indicates that Ghaba may have been domesticating cereals earlier than previously believed. Though the site is a cemetery, little analysis has taken place on the skeletons due to circumstances of the excavation and poor preservation due to the environment. The artifacts at Ghaba suggest the people who used the cemetery were part of a regionalization separating central Sudan's Neolithic from Nubia. While many traditions match with Nubia, the people represented at Ghaba had some of their own particular practices in food production and bead and pottery production, which likely occurred on a relatively small scale. They also had some distinct funerary traditions, as evidenced by their grave goods. The people at Ghaba would have likely existed at least partially in a trade network that spread through the Nile and to the Red Sea. They used agriculture, cultivation, and cattle for sustenance.

References

- Rosen, Steven A. (1997). Lithics after the Stone Age : a handbook of stone tools from the Levant. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press. pp. 55–59. ISBN 0-7619-9123-9.

- Bar-Yosef, Ofer (1998), "The Natufian Culture in the Levant, Threshold to the Origins of Agriculture", Evolutionary Anthropology 6(5): 159–177, doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6505(1998)6:5<159::AID-EVAN4>3.0.CO;2-7, http://www.columbia.edu/itc/anthropology/v1007/baryo.pdf

- "Sickle Gloss". Barbara Ann Kipfer. Retrieved 7 April 2014.