Young County is a county located in the U.S. state of Texas. As of the 2020 census, its population was 17,867. Its county seat is Graham. The county was created in 1856 and organized in 1874. It is named for William Cocke Young, an early Texas settler and soldier.

Kiowa or CáuigúIPA:[kɔ́j-gʷú]) people are a Native American tribe and an Indigenous people of the Great Plains of the United States. They migrated southward from western Montana into the Rocky Mountains in Colorado in the 17th and 18th centuries, and eventually into the Southern Plains by the early 19th century. In 1867, the Kiowa were moved to a reservation in southwestern Oklahoma.

The First Battle of Adobe Walls took place between the United States Army and American Indians. The Kiowa, Comanche and Plains Apache tribes drove from the battlefield a United States Expeditionary Force that was reacting to attacks on white settlers moving into the Southwest. The battle on November 25, 1864, resulted in light casualties on both sides but was one of the largest engagements fought on the Great Plains.

The Red River War was a military campaign launched by the United States Army in 1874 to displace the Comanche, Kiowa, Southern Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes from the Southern Plains, and forcibly relocate the tribes to reservations in Indian Territory. The war had several army columns crisscross the Texas Panhandle in an effort to locate, harass, and capture nomadic Native American bands. Most of the engagements were small skirmishes with few casualties on either side. The war wound down over the last few months of 1874, as fewer and fewer Indian bands had the strength and supplies to remain in the field. Though the last significantly sized group did not surrender until mid-1875, the war marked the end of free-roaming Indian populations on the southern Great Plains.

Comanche history In the 18th and 19th centuries the Comanche became the dominant tribe on the southern Great Plains. The Comanche are often characterized as "Lords of the Plains." They presided over a large area called Comancheria which they shared with allied tribes, the Kiowa, Kiowa-Apache, Wichita, and after 1840 the southern Cheyenne and Arapaho. Comanche power and their substantial wealth depended on horses, trading, and raiding. Adroit diplomacy was also a factor in maintaining their dominance and fending off enemies for more than a century. They subsisted on the bison herds of the Plains which they hunted for food and skins.

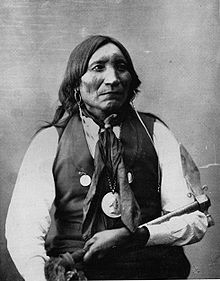

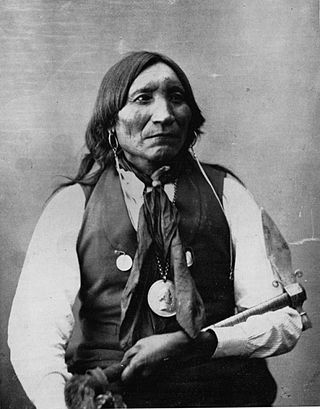

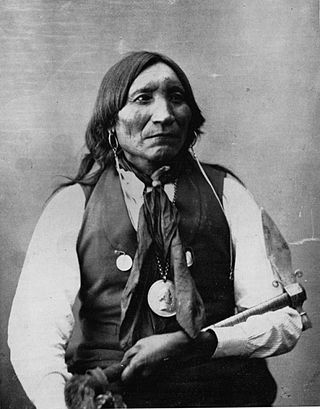

Satanta was a Kiowa war chief. He was a member of the Kiowa tribe, born around 1815, during the height of the power of the Plains Tribes, probably along the Canadian River in the traditional winter camp grounds of his people.

Kicking Bird, also known as Tene-angop'te, "The Kicking Bird", "Eagle Who Strikes with his Talons", or "Striking Eagle" was a High Chief of the Kiowa in the 1870s. It is said that he was given his name for the way he fought his enemies. He was a Kiowa, though his grandfather had been a Crow captive who was adopted by the Kiowa. His mysterious death at Fort Sill on May 3, 1875, is the subject of much debate and speculation.

The Warren Wagon Train raid, also known as the Salt Creek massacre, occurred on May 18, 1871. Henry Warren was contracted to haul supplies to forts in the west of Texas, including Fort Richardson, Fort Griffin, and Fort Concho. Traveling down the Jacksboro-Belknap road heading towards Salt Creek Crossing, they encountered William Tecumseh Sherman. Less than an hour after encountering the famous General, they spotted a rather large group of riders ahead. They quickly realized that these were Native American warriors, probably Kiowa and/or Comanche.

Fort Richardson was a United States Army installation located in present-day Jacksboro, Texas. Named in honor of Union General Israel B. Richardson, who died in the Battle of Antietam during the American Civil War, it was active from 1867 to 1878. Today, the site, with a few surviving buildings, is called Fort Richardson State Park, Historic Site and Lost Creek Reservoir State Trailway. It was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1963 for its role in securing the state's northern frontier in the post-Civil War era.

The Texas–Indian wars were a series of conflicts between settlers in Texas and the Southern Plains Indians during the 19th-century. Conflict between the Plains Indians and the Spanish began before other European and Anglo-American settlers were encouraged—first by Spain and then by the newly Independent Mexican government—to colonize Texas in order to provide a protective-settlement buffer in Texas between the Plains Indians and the rest of Mexico. As a consequence, conflict between Anglo-American settlers and Plains Indians occurred during the Texas colonial period as part of Mexico. The conflicts continued after Texas secured its independence from Mexico in 1836 and did not end until 30 years after Texas became a state of the United States, when in 1875 the last free band of Plains Indians, the Comanches led by Quahadi warrior Quanah Parker, surrendered and moved to the Fort Sill reservation in Oklahoma.

The Little Arkansas Treaty was a set of treaties signed between the United States of America and the Kiowa, Comanche, Plains Apache, Southern Cheyenne, and Southern Arapaho at Little Arkansas River, Kansas in October 1865. On October 14 and 18, 1865 the United States and all of the major Plains Indians Tribes signed a treaty on the Little Arkansas River, which became known as the Little Arkansas Treaty. It is notable in that it lasted less than two years, the reservations it created for the Plains Indians were never created at all, and were reduced by 90% eighteen months later in the Medicine Lodge Treaty.

Dohäsan, Dohosan, Tauhawsin, Tohausen, or Touhason was a prominent Native American. He was War Chief of the Kata or Arikara band of the Kiowa Indians, and then Principal Chief of the entire Kiowa Tribe, a position he held for an extraordinary 33 years. He is best remembered as the last undisputed Principal Chief of the Kiowa people before the Reservation Era, and the battlefield leader of the Plains Tribes in the largest battle ever fought between the Plains tribes and the United States.

The Koitsenko was a group of the ten greatest warriors of the Kiowa tribe as a whole, from all bands. One was Satank who died while being taken to trial for the Warren Wagon Train Raid. The Koitsenko were elected out of the various military societies of the Kiowa, the "Dog Soldiers." They were elected by all the members of all the warrior societies of the entire tribe.

The trial of Satanta and Big Tree occurred in May 1871 in the town of Jacksboro in Jack County, Texas, United States. This historic trial of Native American war chiefs of the Kiowa Indians Satanta and Big Tree for the murder of seven teamsters during a raid on Salt Creek Prairie near Jacksboro, Texas, marked the first time the United States had tried Native American chiefs in a state court. The trial attracted national and international attention. The two Kiowa leaders, with Satank, a legendary third War Chief, were formally indicted on July 1, 1871, and tried shortly thereafter, for acts arising out of the Warren Wagon Train Raid.

White Horse was a chief of the Kiowa. White Horse attended the council between southern plains tribes and the United States at Medicine Lodge in southern Kansas which resulted in the Medicine Lodge Treaty. Despite his attendance at the treaty signing he conducted frequent raids upon other tribes and white settlers. Follower of such elders as Guipago, Satanta and old Satank, he was often associated with Big Tree.

Guipago or Lone Wolf the Elder was the last Principal Chief of the Kiowa tribe. He was a member of the Koitsenko, the Kiowa warrior elite, and was a signer of the Little Arkansas Treaty in 1865.

Big Bow was a Kiowa war leader during the 19th century, an associate of Guipago and Satanta.

Mamante or Mamanti, also known as Swan was a Kiowa medicine man.

Big Red Meat was a Nokoni Comanche chief and a leader of Native American resistance against White invasion during the second half of the 19th century.

Big Tree, Kiowa: Ado-ete, was a noted Kiowa warrior and chief. He was a loyal follower of the fighting chiefs party, and conducted frequent raids upon other tribes and white settlers, often being associated with Tsen-tainte.