Obesity is a medical condition, sometimes considered a disease, in which excess body fat has accumulated to such an extent that it can potentially have negative affects on health. People are classified as obese when their body mass index (BMI)—a person's weight divided by the square of the person's height—is over 30 kg/m2; the range 25–30 kg/m2 is defined as overweight. Some East Asian countries use lower values to calculate obesity. Obesity is a major cause of disability and is correlated with various diseases and conditions, particularly cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, obstructive sleep apnea, certain types of cancer, and osteoarthritis.

Childhood obesity is a condition where excess body fat negatively affects a child's health or well-being. As methods to determine body fat directly are difficult, the diagnosis of obesity is often based on BMI. Due to the rising prevalence of obesity in children and its many adverse health effects it is being recognized as a serious public health concern. The term 'overweight' rather than 'obese' is often used when discussing childhood obesity, as it is less stigmatizing, although the term 'overweight' can also refer to a different BMI category. The prevalence of childhood obesity is known to differ by sex and gender.

Obesity in Mexico is a relatively recent phenomenon, having been widespread since the 1980s with the introduction of ultra-processed food into much of the Mexican food market. Prior to that, dietary issues were limited to under and malnutrition, which is still a problem in various parts of the country. Following trends already ongoing in other parts of the world, Mexicans have been foregoing the traditional Mexican diet high in whole grains, fruits, legumes and vegetables in favor of a diet with more animal products and ultra-processed foods. It has seen dietary energy intake and rates of overweight and obese people rise with seven out of ten at least overweight and a third clinically obese.

Obesity is common in the United States and is a major health issue associated with numerous diseases, specifically an increased risk of certain types of cancer, coronary artery disease, type 2 diabetes, stroke, and cardiovascular disease, as well as significant increases in early mortality and economic costs.

Being overweight or fat is having more body fat than is optimally healthy. Being overweight is especially common where food supplies are plentiful and lifestyles are sedentary.

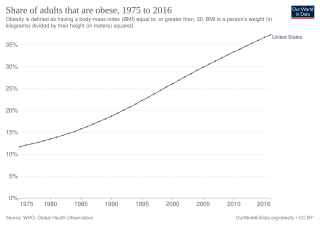

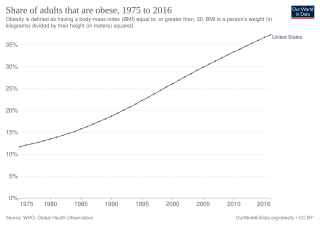

Obesity has been observed throughout human history. Many early depictions of the human form in art and sculpture appear obese. However, it was not until the 20th century that obesity became common — so much so that, in 1997, the World Health Organization (WHO) formally recognized obesity as a global epidemic and estimated that the worldwide prevalence of obesity has nearly tripled since 1975. Obesity is defined as having a body mass index (BMI) greater than or equal to 30 kg/m2, and in June 2013 the American Medical Association classified it as a disease.

Obesity in Canada is a growing health concern, which is "expected to surpass smoking as the leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality" and represents a burden of Can$3.96 (US$3.04/€2.75) billion on the Canadian economy each year."

Despite India's 50% increase in GDP since 2013, more than one third of the world's malnourished children live in India. Among these, half of the children under three years old are underweight.

Diet plays an important role in the genesis of obesity. Personal choices, food advertising, social customs and cultural influences, as well as food availability and pricing all play a role in determining what and how much an individual eats.

Weight management refers to behaviors, techniques, and physiological processes that contribute to a person's ability to attain and maintain a healthy weight. Most weight management techniques encompass long-term lifestyle strategies that promote healthy eating and daily physical activity. Moreover, weight management involves developing meaningful ways to track weight over time and to identify ideal body weights for different individuals.

Research into food choice investigates how people select the food they eat. An interdisciplinary topic, food choice comprises psychological and sociological aspects, economic issues and sensory aspects.

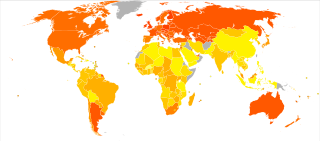

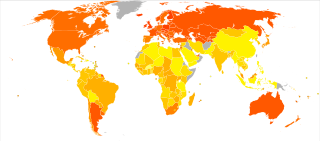

Obesity in the Middle East and North Africa is a notable health issue. Out of the fifteen fattest nations in the world as of 2014, 5 were located in the Middle East and North Africa region.

The term "Freshman 15" is an expression commonly used in the United States and Canada that refers to an amount of weight gained during a student's first year at college. In Australia and New Zealand, it is sometimes referred to as "First Year Fatties", "Fresher Spread", or "Fresher Five", the latter referring to a five-kilogram gain.

Criticism of fast food includes claims of negative health effects, animal cruelty, cases of worker exploitation, children-targeted marketing and claims of cultural degradation via shifts in people's eating patterns away from traditional foods. Fast food chains have come under fire from consumer groups, such as the Center for Science in the Public Interest, a longtime fast food critic over issues such as caloric content, trans fats and portion sizes. Social scientists have highlighted how the prominence of fast food narratives in popular urban legends suggests that modern consumers have an ambivalent relationship with fast food, particularly in relation to children.

Social class differences in food consumption refers to how the quantity and quality of food varies according to a person's social status or position in the social hierarchy. Various disciplines, including social, psychological, nutritional, and public health sciences, have examined this topic. Social class can be examined according to defining factors — education, income, or occupational status — or subjective components, like perceived rank in society.

School meals are provided free of charge, or at a government-subsidized price, to United States students from low-income families. These free or subsidized meals have the potential to increase household food security, which can improve children's health and expand their educational opportunities. A study of a free school meal program in the United States found that providing free meals to elementary and middle school children in areas characterized by high food insecurity led to increased school discipline among the students.

Childhood obesity is defined as a body mass index (BMI) at or above the 96th percentile for children of the same age and sex. It can cause a variety of health problems, including high blood pressure, high cholesterol, heart disease, diabetes, breathing problems, sleeping problems, and joint problems later in life. Children who are obese are at a greater risk for social and psychological problems as well, such as peer victimization, increased levels of aggression, and low self-esteem. Many environmental and social factors have been shown to correlate with childhood obesity, and researchers are attempting to use this knowledge to help prevent and treat the condition. When implemented early, certain forms of behavioral and psychological treatment can help children regain and/or maintain a healthy weight.

Obesity and the environment aims to look at the different environmental factors that researchers worldwide have determined cause and perpetuate obesity. Obesity is a condition in which a person's weight is higher than what is considered healthy for their height, and is the leading cause of preventable death worldwide. Obesity can result from several factors such as poor nutritional choices, overeating, genetics, culture, and metabolism. Many diseases and health complications are associated with obesity. Worldwide, the rates of obesity have nearly tripled since 1975, leading health professionals to label the condition as a modern epidemic in most parts of the world. Current worldwide population estimates of obese adults are near 13%; overweight adults total approximately 39%.

Nutrition is the intake of food, considered in relation to the body's dietary needs. Well-maintained nutrition includes a balanced diet as well as a regular exercise routine. Nutrition is an essential aspect of everyday life as it aids in supporting mental as well as physical body functioning. The National Health and Medical Research Council determines the Dietary Guidelines within Australia and it requires children to consume an adequate amount of food from each of the five food groups, which includes fruit, vegetables, meat and poultry, whole grains as well as dairy products. Nutrition is especially important for developing children as it influences every aspect of their growth and development. Nutrition allows children to maintain a stable BMI, reduces the risks of developing obesity, anemia and diabetes as well as minimises child susceptibility to mineral and vitamin deficiencies.

Obesity is defined as the excessive accumulation of fat and is predominantly caused when there is an energy imbalance between calorie consumption and calorie expenditure. Childhood obesity is becoming an increasing concern worldwide, and Australia alone recognizes that 1 in 4 children are either overweight or obese.