Related Research Articles

American Sign Language (ASL) is a natural language that serves as the predominant sign language of Deaf communities in the United States of America and most of Anglophone Canada. ASL is a complete and organized visual language that is expressed by employing both manual and nonmanual features. Besides North America, dialects of ASL and ASL-based creoles are used in many countries around the world, including much of West Africa and parts of Southeast Asia. ASL is also widely learned as a second language, serving as a lingua franca. ASL is most closely related to French Sign Language (LSF). It has been proposed that ASL is a creole language of LSF, although ASL shows features atypical of creole languages, such as agglutinative morphology.

Sign languages are languages that use the visual-manual modality to convey meaning, instead of spoken words. Sign languages are expressed through manual articulation in combination with non-manual markers. Sign languages are full-fledged natural languages with their own grammar and lexicon. Sign languages are not universal and are usually not mutually intelligible, although there are also similarities among different sign languages.

International Sign (IS) is a pidgin sign language which is used in a variety of different contexts, particularly as an international auxiliary language at meetings such as the World Federation of the Deaf (WFD) congress, in some European Union settings, and at some UN conferences, at events such as the Deaflympics, the Miss & Mister Deaf World, and Eurovision, and informally when travelling and socialising.

British Sign Language (BSL) is a sign language used in the United Kingdom and is the first or preferred language among the deaf community in the UK. Based on the percentage of people who reported 'using British Sign Language at home' on the 2011 Scottish Census, the British Deaf Association estimates there are 151,000 BSL users in the UK, of whom 87,000 are Deaf. By contrast, in the 2011 England and Wales Census 15,000 people living in England and Wales reported themselves using BSL as their main language. People who are not deaf may also use BSL, as hearing relatives of deaf people, sign language interpreters or as a result of other contact with the British Deaf community. The language makes use of space and involves movement of the hands, body, face and head.

Auslan is the sign language used by the majority of the Australian Deaf community. The term Auslan is a portmanteau of "Australian Sign Language", coined by Trevor Johnston in the 1980s, although the language itself is much older. Auslan is related to British Sign Language (BSL) and New Zealand Sign Language (NZSL); the three have descended from the same parent language, and together comprise the BANZSL language family. Auslan has also been influenced by Irish Sign Language (ISL) and more recently has borrowed signs from American Sign Language (ASL).

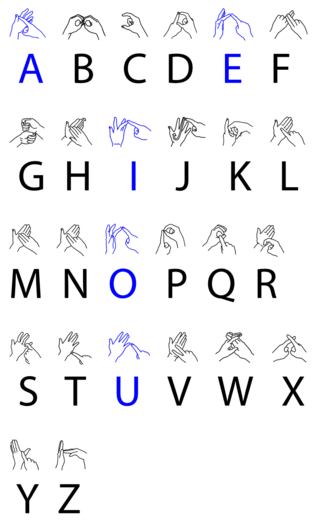

The American Manual Alphabet (AMA) is a manual alphabet that augments the vocabulary of American Sign Language.

Manually Coded English (MCE) is a type of sign system that follows direct spoken English. The different codes of MCE vary in the levels of directness in following spoken English grammar. There may also be a combination with other visual clues, such as body language. MCE is typically used in conjunction with direct spoken English.

Japanese Sign Language, also known by the acronym JSL, is the dominant sign language in Japan and is a complete natural language, distinct from but influenced by the spoken Japanese language.

South African Sign Language is the primary sign language used by deaf people in South Africa. The South African government added a National Language Unit for South African Sign Language in 2001. SASL is not the only manual language used in South Africa, but it is the language that is being promoted as the language to be used by the Deaf in South Africa, although Deaf peoples in South Africa historically do not form a single group.

A contact sign language, or contact sign, is a variety or style of language that arises from contact between deaf individuals using a sign language and hearing individuals using an oral language. Contact languages also arise between different sign languages, although the term pidgin rather than contact sign is used to describe such phenomena.

The Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, also known as AG Bell, is an organization that aims to promote listening and spoken language among people who are deaf and hard of hearing. It is headquartered in Washington, D.C., with chapters located throughout the United States and a network of international affiliates.

Kata Kolok, also known as Benkala Sign Language and Balinese Sign Language, is a village sign language which is indigenous to two neighbouring villages in northern Bali, Indonesia. The main village, Bengkala, has had high incidences of deafness for over seven generations. Notwithstanding the biological time depth of the recessive mutation that causes deafness, the first substantial cohort of deaf signers did not occur until five generations ago, and this event marks the emergence of Kata Kolok. The sign language has been acquired by at least five generations of deaf, native signers and features in all aspects of village life, including political, professional, educational, and religious settings.

Bimodal bilingualism is an individual or community's bilingual competency in at least one oral language and at least one sign language, which utilize two different modalities. An oral language consists of a vocal-aural modality versus a signed language which consists of a visual-spatial modality. A substantial number of bimodal bilinguals are children of deaf adults (CODA) or other hearing people who learn sign language for various reasons. Deaf people as a group have their own sign language(s) and culture that is referred to as Deaf, but invariably live within a larger hearing culture with its own oral language. Thus, "most deaf people are bilingual to some extent in [an oral] language in some form" In discussions of multilingualism in the United States, bimodal bilingualism and bimodal bilinguals have often not been mentioned or even considered, in part because American Sign Language, the predominant sign language used in the U.S., only began to be acknowledged as a natural language in the 1960s. However, bimodal bilinguals share many of the same traits as traditional bilinguals, as well as differing in some interesting ways, due to the unique characteristics of the Deaf community. Bimodal bilinguals also experience similar neurological benefits as do unimodal bilinguals, with significantly increased grey matter in various brain areas and evidence of increased plasticity as well as neuroprotective advantages that can help slow or even prevent the onset of age-related cognitive diseases, such as Alzheimer's and dementia.

Singapore Sign Language, or SgSL, is the native sign language used by the deaf and hard of hearing in Singapore, developed over six decades since the setting up of the first school for the Deaf in 1954. Since Singapore's independence in 1965, the Singapore deaf community has had to adapt to many linguistic changes. Today, the local deaf community recognises Singapore Sign Language (SgSL) as a reflection of Singapore's diverse linguistic culture. SgSL is influenced by Shanghainese Sign Language (SSL), American Sign Language (ASL), Signing Exact English (SEE-II) and locally developed signs.

Deaf education is the education of students with any degree of hearing loss or deafness. This may involve, but does not always, individually-planned, systematically-monitored teaching methods, adaptive materials, accessible settings, and other interventions designed to help students achieve a higher level of self-sufficiency and success in the school and community than they would achieve with a typical classroom education. There are different language modalities used in educational setting where students get varied communication methods. A number of countries focus on training teachers to teach deaf students with a variety of approaches and have organizations to aid deaf students.

Claire L Ramsey is an American linguist. Ramsey is an Associate Professor Emerita at the University of California, San Diego. She is an alumna of Gallaudet University and is former instructor at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, Nebraska. Ramsey's research has focused on the sociolinguistics of deaf and signing communities in the US and Mexico.

Language acquisition is a natural process in which infants and children develop proficiency in the first language or languages that they are exposed to. The process of language acquisition is varied among deaf children. Deaf children born to deaf parents are typically exposed to a sign language at birth and their language acquisition follows a typical developmental timeline. However, at least 90% of deaf children are born to hearing parents who use a spoken language at home. Hearing loss prevents many deaf children from hearing spoken language to the degree necessary for language acquisition. For many deaf children, language acquisition is delayed until the time that they are exposed to a sign language or until they begin using amplification devices such as hearing aids or cochlear implants. Deaf children who experience delayed language acquisition, sometimes called language deprivation, are at risk for lower language and cognitive outcomes. However, profoundly deaf children who receive cochlear implants and auditory habilitation early in life often achieve expressive and receptive language skills within the norms of their hearing peers; age at implantation is strongly and positively correlated with speech recognition ability. Early access to language through signed language or technology have both been shown to prepare children who are deaf to achieve fluency in literacy skills.

Black American Sign Language (BASL) or Black Sign Variation (BSV) is a dialect of American Sign Language (ASL) used most commonly by deaf African Americans in the United States. The divergence from ASL was influenced largely by the segregation of schools in the American South. Like other schools at the time, schools for the deaf were segregated based upon race, creating two language communities among deaf signers: black deaf signers at black schools and white deaf signers at white schools. As of the mid 2010s, BASL is still used by signers in the South despite public schools having been legally desegregated since 1954.

Ceil (Kovac) Lucas is an American linguist and a professor emerita of Gallaudet University, best known for her research on American Sign Language.

References

- ↑ Lucas, Ceil (2001). The Sociolinguistics of Sign Languages. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521-79137-5.

- ↑ Bayley, Robert, et al. "The Study of Language and Society." The Oxford Handbook of Sociolinguistics, Jan. 2013, p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lucas, Ceil, ed. (2001). "Sociolinguistic Variation". The Sociolinguistics of Sign Languages. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-79474-9.

- 1 2 3 4 LeMaster, Barbara (1991). The Life of Language: Papers in Linguistics in Honor of William Bright. Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter & Co. ISBN 978-3-11-015633-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Aramburo, Anthony (2000). Valli, Clayton; Lucas, Ceil (eds.). Linguistics of American Sign Language: An Introduction. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press. ISBN 978-1-56368-097-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ann, Jean (2001). "Bilingualism and Language Contact". In Lucas, Ceil (ed.). The Sociolinguistics of Sign Languages. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 33–60. ISBN 0521791375.

- 1 2 3 Palmer, Jeffrey Levi; Reynolds, Wanette; Minor, Rebecca (2012). "You Want What on Your Pizza". Sign Language Studies. Gallaudet University Press. 12 (3): 371–397. doi:10.1353/sls.2012.0005. S2CID 145223579.

- ↑ Quinto-Pozos, David; Reynolds, Wanette (2012). "ASL Discourse Strategies: Chaining and Connecting-Explaining across Audiences". Sign Language Studies. Gallaudet University Press. 12 (2): 211–235. doi:10.1353/sls.2011.0021. S2CID 143937631.