An army, ground force or land force is an armed force that fights primarily on land. In the broadest sense, it is the land-based military branch, service branch or armed service of a nation or country. It may also include aviation assets by possessing an army aviation component. Within a national military force, the word army may also mean a field army.

The Thirty Years' War, from 1618 to 1648, was one of the most destructive conflicts in European history. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died from the effects of battle, famine, or disease, while parts of Germany reported population declines of over 50%. Related conflicts include the Eighty Years' War, the War of the Mantuan Succession, the Franco-Spanish War, the Torstenson War, the Dutch-Portuguese War, and the Portuguese Restoration War.

A mercenary, also called a merc, soldier of fortune, or hired gun, is a private individual who joins an armed conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any other official military. Mercenaries fight for money or other forms of payment rather than for political interests.

The Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel, spelled Hesse-Cassel during its entire existence, also known as the Hessian Palatinate, was a state of the Holy Roman Empire. The state was created in 1567 when the Landgraviate of Hesse was divided upon the death of Philip I, Landgrave of Hesse. His eldest son William IV inherited the northern half of the Landgraviate and the capital of Kassel. The other sons received the Landgraviates of Hesse-Marburg, Hesse-Rheinfels and Hesse-Darmstadt.

A private military company (PMC) or private military and security company (PMSC) is a private company providing armed combat or security services for financial gain. PMCs refer to their personnel as "security contractors" or "private military contractors".

Condottieri were Italian military leaders during the Middle Ages and the early modern period. The definition originally applied only to commanders of mercenary companies, condottiero in medieval Italian meaning 'contractor' and condotta being the contract by which the condottieri put themselves in the service of a city or lord. The term, however, came to refer to all the famed Italian military leaders of the Renaissance, Reformation and Counter-Reformation eras. Notable condottieri include Prospero Colonna, Giovanni dalle Bande Nere, Cesare Borgia, the Marquis of Pescara, Andrea Doria, and the Duke of Parma. They served Popes and other European monarchs and states during the Italian Wars and the European wars of religion.

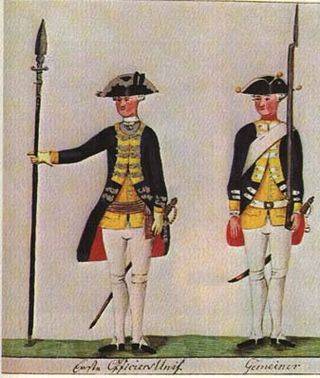

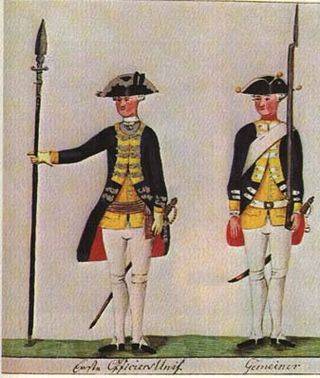

Hessians were German soldiers who served as auxiliaries to the British Army in several major wars in the 18th century, most notably the American Revolutionary War. The term is a synecdoche for all Germans who fought on the British side, since 65% came from the German states of Hesse-Kassel and Hesse-Hanau. Known for their discipline and martial prowess, around 30,000 to 37,000 Hessians fought in the war, comprising approximately 25% of British land forces.

The Swiss mercenaries were a powerful infantry force constituted by professional soldiers originating from the cantons of the Old Swiss Confederacy. They were notable for their service in foreign armies, especially among the military forces of the kings of France, throughout the early modern period of European history, from the Late Middle Ages into the 19th century. Their service as mercenaries was at its peak during the Renaissance, when their proven battlefield capabilities made them sought-after mercenary troops. There followed a period of decline, as technological and organizational advances counteracted the Swiss' advantages. Switzerland's military isolationism largely put an end to organized mercenary activity; the principal remnant of the practice is the Pontifical Swiss Guard at the Vatican.

The Royal Netherlands East Indies Army was the military force maintained by the Kingdom of the Netherlands in its colony of the Dutch East Indies, in areas that are now part of Indonesia. The KNIL's air arm was the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army Air Force. Elements of the Royal Netherlands Navy and Government Navy were also stationed in the Netherlands East Indies.

Wilhelm Reichsfreiherr von Innhausen und Knyphausen was a German general officer who served in Hesse-Kassel. He fought in the American Revolutionary War, during which he commanded Hessian auxiliaries on behalf of Great Britain.

Irregular military is any non-standard military component that is distinct from a country's national armed forces. Being defined by exclusion, there is significant variance in what comes under the term. It can refer to the type of military organization, or to the type of tactics used. An irregular military organization is one which is not part of the regular army organization. Without standard military unit organization, various more general names are often used; such organizations may be called a troop, group, unit, column, band, or force. Irregulars are soldiers or warriors that are members of these organizations, or are members of special military units that employ irregular military tactics. This also applies to irregular infantry and irregular cavalry units.

The British Army came into being with the unification of the Kingdoms of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England and Scotland. The Army has traditionally relied on volunteer recruits, the only exceptions to this being during the latter part of the First World War until 1919, and then again during the Second World War when conscription was brought in during the war and stayed until 1960.

The military of Carthage was one of the largest military forces in the ancient world. Although Carthage's navy was always its main military force, the army acquired a key role in the spread of Carthaginian power over the native peoples of northern Africa and southern Iberian Peninsula from the 6th century BC and the 3rd century BC. Carthage's military also allowed it to expand into Sardinia and the Balearic Islands. This expansion transformed the military from a body of citizen-soldiers into a multinational force composed of a combination of allies, citizens and foreign mercenary units.

People of German ancestry fought on both sides in the American Revolution. Many of the small German states in Europe supported the British. King George III of Britain was simultaneously the ruler of the German state of Hanover. Around 30,000 Germans fought for the British during the war, around 25% of British land forces. In particular, 12,000 Hessian soldiers served as Auxiliaries on the side of British. However some Germans who were supporters of Congress as individuals crossed the Atlantic to help the Patriots.

The Treaty of Bärwalde, signed on 23 January 1631, was an agreement by France to provide Sweden financial support, following its intervention in the Thirty Years' War.

The Dutch States Army was the army of the Dutch Republic. It was usually called this, because it was formally the army of the States-General of the Netherlands, the sovereign power of that federal republic. This army was brought to such a size and state of readiness that it was able to hold its own against the armies of the major European powers of the extended 17th century, Habsburg Spain and the France of Louis XIV, despite the fact that these powers possessed far larger military resources than the Republic. It played a major role in the Eighty Years' War and in the wars of the Grand Alliance with France after 1672.

Imperial Army or Imperial Troops was a name used for several centuries, especially to describe soldiers recruited for the Holy Roman Emperor during the early modern period. The Imperial Army of the Emperor should not be confused with the Army of the Holy Roman Empire, which could only be deployed with the consent of the Imperial Diet. The Imperialists effectively became a standing army of troops under the Habsburg Emperors from the House of Austria, which is why they were also increasingly described in the 18th century as "Austrians", although its troops were recruited not just from the Archduchy of Austria but from all over the Holy Roman Empire.

Troops from Hesse-Hanau served as auxiliaries to the British Army during the American Revolutionary War, in accordance with the treaty of 1776 between Great Britain and the small principality. A regiment of foot, an artillery company, a ranger corp and a light infantry corp served in British America. A total of 2,422 soldiers were sent, with 1,441 returning, the remainder not surviving or choosing to remain in North America. As compensation, the reigning Count of Hesse-Hanau received a total of 343,110 pounds sterling from the British government.

The Rhodesian government actively recruited white personnel from other countries from the mid-1970s until 1980 to address manpower shortages in the Rhodesian Security Forces during the Rhodesian Bush War. It is estimated that between 800 and 2,000 foreign volunteers enlisted. The issue attracted a degree of controversy as Rhodesia was the subject of international sanctions that banned military assistance due to its illegal declaration of independence and the control which the small white minority exerted over the country. The volunteers were often labelled as mercenaries by opponents of the Rhodesian regime, though the Rhodesian government did not regard or pay them as such.