Related Research Articles

Urban design is an approach to the design of buildings and the spaces between them that focuses on specific design processes and outcomes. In addition to designing and shaping the physical features of towns, cities, and regional spaces, urban design considers 'bigger picture' issues of economic, social and environmental value and social design. The scope of a project can range from a local street or public space to an entire city and surrounding areas. Urban designers connect the fields of architecture, landscape architecture and urban planning to better organize physical space and community environments.

Gottfried Semper was a German architect, art critic, and professor of architecture who designed and built the Semper Opera House in Dresden between 1838 and 1841. In 1849 he took part in the May Uprising in Dresden and was put on the government's wanted list. He fled first to Zürich and later to London. He returned to Germany after the 1862 amnesty granted to the revolutionaries.

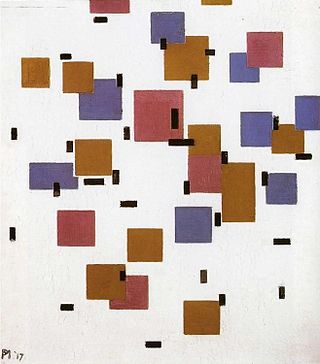

Neoplasticism, originating from the Dutch Nieuwe Beelding, is an avant-garde art theory that arose in 1917 and was employed by the Dutch De Stijl group of artists. The most notable advocates of the theory were the painters Theo van Doesburg and Piet Mondriaan. Neo-plasticism advocated for a purified abstract art, by applying the most elementary principles through rational means. Thus, a painting that adhered to neo-plastic theory would typically consist of simple geometric shapes, right-angled relationships and primary colors.

The early history of gardening is largely entangled with the history of agriculture, with gardens that were mainly ornamental generally the preserve of the elite until quite recent times. Smaller gardens generally had being a kitchen garden as their first priority, as is still often the case.

Garrett Eckbo was an American landscape architect notable for his seminal 1950 book Landscape for Living.

John Fletcher Steele was an American landscape architect credited with designing and creating over 700 gardens from 1915 to the time of his death.

Urban morphology is the study of the formation of human settlements and the process of their formation and transformation. The study seeks to understand the spatial structure and character of a metropolitan area, city, town or village by examining the patterns of its component parts and the ownership or control and occupation. Typically, analysis of physical form focuses on street pattern, lot pattern and building pattern, sometimes referred to collectively as urban grain. Analysis of specific settlements is usually undertaken using cartographic sources and the process of development is deduced from comparison of historic maps.

In geometry, an isovist is the volume of space visible from a given point in space, together with a specification of the location of that point. It is a geometric concept coined by Clifford Tandy in 1967 and further refined by the architect Michael Benedikt.

Arthur Coney Tunnard, later known as Christopher Tunnard, was a Canadian-born landscape architect, garden designer, city-planner, and author of Gardens in the Modern Landscape (1938).

Daniel Urban Kiley was an American landscape architect, who worked in the style of modern architecture. Kiley designed over one-thousand landscape projects including Gateway Arch National Park in St. Louis.

James C. Rose (1913–1991) was a prominent landscape architect and author of the twentieth century. Born in rural Pennsylvania he, his mother and older sister moved to New York after his father's death. Rose was a high school dropout, but this didn't stop him from being accepted into Cornell University as an architecture student. Later he transferred to Harvard University as a landscape architecture major. In 1937, he was expelled because his design style didn't fit into Harvard's program. In 1938 and 1939 Rose published a series of articles containing the design experiment ideas that led to his expulsion from Harvard. He later published numerous articles and books which heavily impacted design theory and practice in the twentieth century. In 1941, Rose worked for Tuttle, Seelye, Place and Raymond in New York where he became discouraged by the limitations of large public works, and decided that working on private gardens was more suiting to his style. Despite his dislike of the institution of school, Rose would often make appearances as a guest lecturer at schools of landscape architecture and architecture. Before his death he was able to fulfill his lifelong dream of establishing a design study and landscape research center, the James Rose Center. After Rose's death from cancer in 1991, he bequeathed his home in Ridgewood to the James Rose Center.

Lebbeus Woods was an American architect and artist known for his unconventional and experimental designs. Known for his rich, yet mainly unbuilt work and its nonetheless significant impact on the architectural sphere, Lebbeus Woods and his oeuvre are considered visionary, describing a radically experimental world built on the principles of heterogeneity and multiplicity and bridging thus the gap between numerous fields including architecture, philosophy, and mathematics. Reconfiguring the architectural space in environments of crisis, whether it be natural, social, political, or financial, Woods stated: “I’m not interested in living in a fantasy world. All my work is still meant to evoke real architectural spaces. But what interests me is what the world would be like if we were free of conventional limits. Maybe I can show what could happen if we lived by a different set of rules.”

Architectural theory is the act of thinking, discussing, and writing about architecture. Architectural theory is taught in all architecture schools and is practiced by the world's leading architects. Some forms that architecture theory takes are the lecture or dialogue, the treatise or book, and the paper project or competition entry. Architectural theory is often didactic, and theorists tend to stay close to or work from within schools. It has existed in some form since antiquity, and as publishing became more common, architectural theory gained an increased richness. Books, magazines, and journals published an unprecedented number of works by architects and critics in the 20th century. As a result, styles and movements formed and dissolved much more quickly than the relatively enduring modes in earlier history. It is to be expected that the use of the internet will further the discourse on architecture in the 21st century.

The discussion of the history of landscape architecture is a complex endeavor as it shares much of its history with that of landscape gardening and architecture, spanning the entirety of man's existence. However, it was not until relatively recent history that the term "landscape architecture" or even "landscape architect" came into common use.

Landscape urbanism is a theory of urban design arguing that the city is constructed of interconnected and ecologically rich horizontal field conditions, rather than the arrangement of objects and buildings. Landscape Urbanism, like Infrastructural Urbanism and Ecological Urbanism, emphasizes performance over pure aesthetics and utilizes systems-based thinking and design strategies. The phrase 'landscape urbanism' first appeared in the mid 1990s. Since this time, the phrase 'landscape urbanism' has taken on many different uses, but is most often cited as a postmodernist or post-postmodernist response to the "failings" of New Urbanism and the shift away from the comprehensive visions, and demands, for modern architecture and urban planning.

A trellis (treillage) is an architectural structure, usually made from an open framework or lattice of interwoven or intersecting pieces of wood, bamboo or metal that is normally made to support and display climbing plants, especially shrubs.

Robert N. Royston was one of America's most distinguished landscape architects, based in the San Francisco Bay Area of California in the United States. His design work and university teaching in the years following World War II helped define and establish the California modernism style in the post-war period. During his sixty years of professional practice Royston completed an array of award-winning projects that ranged from residential gardens to regional land use plans. He is perhaps best known for his important innovations in park design. A recent book, Modern Public Gardens: Robert Royston and the Suburban Park, details this area of his professional creativity and philosophy.

The Miller House and Garden, also known as Miller House, is a mid-century modern home designed by Eero Saarinen and located in Columbus, Indiana, United States. The residence, commissioned by American industrialist, philanthropist, and architecture patron J. Irwin Miller and his wife Xenia Simons Miller in 1953, is now owned by Newfields. Miller supported modern architecture in the construction of a number of buildings throughout Columbus, Indiana. Design and construction on the Miller House took four years and was completed in 1957. The house stands at 2860 Washington St, Columbus Indiana, and was declared a National Historic Landmark in 2000. The Miller family owned the home until 2008, when Xenia Miller, the last resident of the home, died.

David Schafer is an American visual and sound artist based in Los Angeles, whose practice integrates aural, textual, graphic and sculptural elements to create installations, public art and individual works that critics describe as immersive, spatial experiments. His approach combines self-consciously formalist aesthetics, a Pop Art sensibility, and postmodern Deconstructionist intent, often appropriating and reframing cultural motifs in order to investigate systems of historical and cultural memory, built space, and language. Schafer has exhibited nationally and internationally in museums, galleries and public spaces, including the Whitney Museum of American Art, MoMA PS1, The Drawing Center, MASS MoCA, Baltimore Museum of Art, Long Beach Museum of Art, SculptureCenter, and Vleeshal Middelburg. He has received awards from the Pollock-Krasner Foundation and National Endowment for the Arts, among others, as well as public commissions from the Public Art Fund of New York and the Los Angeles County Arts Commission. Los Angeles Times critic Leah Ollman describes his work as a "heady jumble" producing collisions, contradictions and convergences at the intersection of architecture, sound, sculpture, language and theory in order to "disrupt communication intentionally, incisively, through strategies of fragmentation and interruption." Schafer has taught sculpture, art theory, digital media and sound at institutions on the East and West coasts since 1985, and is currently on the Fine Arts faculty at Art Center College of Design in Los Angeles.

Sculptures Bachelard is an In Situ work by French artist Jean-Max Albert installed in 1986 in the Parc de la Villette, Paris, France. It is named after the author of The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard. It consists of a set of 8 sculptures arranged around the perimeter of the Jardin de la Treille.

References

- ↑ Meyer, lecture notes: "The Spatial medium of modernism between open space and figural space/Kiley's articulated spaces and multivalent landscapes: abstract modern grid and contextual response/The grid, the bosque, the allée. Planted form as spatial device".

- ↑ Adrian Forty, Words and Building: A Vocabulary of Modern Architecture (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2000), 256-275.

- ↑ James Rose, "Plant Forms and Space" Pencil Points 10(1938), 227.

- ↑ "The Sensation of Space", "The Elements of Enclosed Space", and "Urbanism and Spatial Order", 1941-1942.

- ↑ Bachelard's The Poetics of Space was published in 1951 and had immense influence on designers and artists.

- ↑ James Corner, "Representation and landscape: drawing and making in the landscape medium" Word & Image 8(July-Sept. 1992) 246.