Elizabeth I was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last monarch of the House of Tudor.

Anne Boleyn was Queen of England from 1533 to 1536, as the second wife of King Henry VIII. The circumstances of her marriage and of her execution by beheading for treason and other charges made her a key figure in the political and religious upheaval that marked the start of the English Reformation.

Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, KG, PC was an English nobleman and a favourite of Queen Elizabeth I. Politically ambitious, and a committed general, he was placed under house arrest following a poor campaign in Ireland during the Nine Years' War in 1599. In 1601, he led an abortive coup d'état against the government of Elizabeth I and was executed for treason.

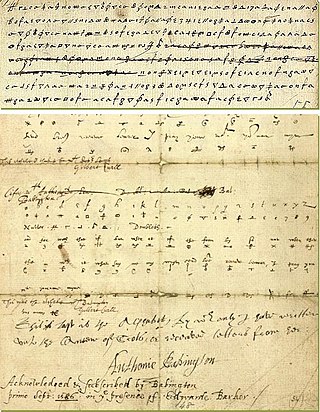

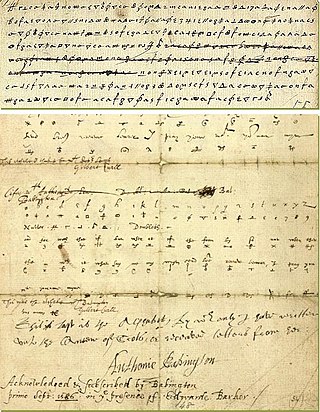

The Babington Plot was a plan in 1586 to assassinate Queen Elizabeth I, a Protestant, and put Mary, Queen of Scots, her Catholic cousin, on the English throne. It led to Mary's execution, a result of a letter sent by Mary in which she consented to the assassination of Elizabeth.

The Faerie Queene is an English epic poem by Edmund Spenser. Books I–III were first published in 1590, then republished in 1596 together with books IV–VI. The Faerie Queene is notable for its form: at over 36,000 lines and over 4,000 stanzas, it is one of the longest poems in the English language; it is also the work in which Spenser invented the verse form known as the Spenserian stanza. On a literal level, the poem follows several knights as a means to examine different virtues, and though the text is primarily an allegorical work, it can be read on several levels of allegory, including as praise of Queen Elizabeth I. In Spenser's "Letter of the Authors", he states that the entire epic poem is "cloudily enwrapped in Allegorical devices", and that the aim of publishing The Faerie Queene was to "fashion a gentleman or noble person in virtuous and gentle discipline".

Regnans in Excelsis is a papal bull that Pope Pius V issued on 25 February 1570. It excommunicated Queen Elizabeth I of England, referring to her as "the pretended Queen of England and the servant of crime", declared her a heretic, and released her subjects from allegiance to her, even those who had "sworn oaths to her", and excommunicated any who obeyed her orders: "We charge and command all and singular the nobles, subjects, peoples and others afore said that they do not dare obey her orders, mandates and laws. Those who shall act to the contrary we include in the like sentence of excommunication."

Charles Howard, 1st Earl of Nottingham, 2nd Baron Howard of Effingham, KG, known as Lord Howard of Effingham, was an English statesman and Lord High Admiral under Elizabeth I and James I. He was commander of the English forces during the battles against the Spanish Armada and was chiefly responsible for the victory that saved England from invasion by the Spanish Empire.

The Union of the Crowns was the accession of James VI of Scotland to the throne of the Kingdom of England as James I and the practical unification of some functions of the two separate realms under a single individual on 24 March 1603. Whilst a misnomer, therefore, what is popularly known as "The Union of the Crowns" followed the death of James's cousin, Elizabeth I of England, the last monarch of the Tudor dynasty.

The Virgin Queen is a 2005 BBC and Power co-production, four-part miniseries based upon the life of Queen Elizabeth I, starring Anne-Marie Duff and Tom Hardy as Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester. It was nominated for the BAFTA TV Award for Best Drama Serial in 2007.

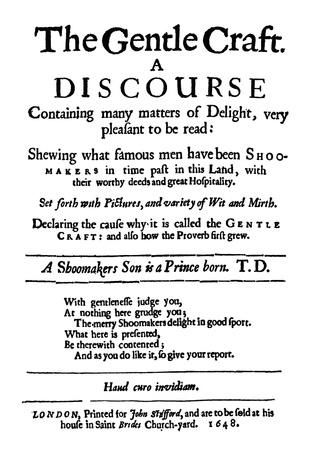

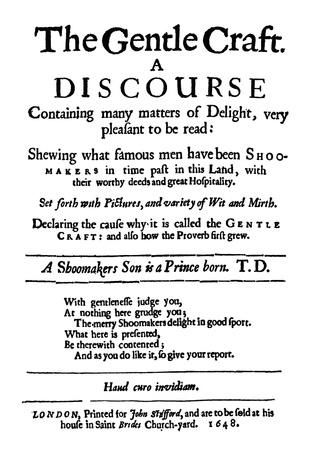

Thomas Deloney was an English silk-weaver, novelist, and ballad writer.

The Tenterfield Oration was a speech given by Sir Henry Parkes, Premier of the Colony of New South Wales at the Tenterfield School of Arts in Tenterfield, in rural New South Wales, Australia, on 24 October 1889. In the Oration, Parkes called for the Federation of the six Australian colonies, which were at the time self-governing but under the distant central authority of the British Colonial Secretary. The speech is considered to be the start of the federation process in Australia, which led to the foundation of the Commonwealth of Australia 12 years later.

Maria W. Stewart was an American teacher, journalist, abolitionist and lecturer known for her role in the anti-slavery and women's rights movements in the United States. The first known American woman to speak to a mixed audience of men and women, white and black, she was also the first African American woman to make public lectures, as well as to lecture about women's rights and make a public speech opposing slavery.

Fire Over England is a 1937 London Film Productions film drama, notable for providing the first pairing of Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh. It was directed by William K. Howard and written by Clemence Dane, nominally from the 1936 novel Fire Over England by AEW Mason. Leigh's performance in the film helped to convince David O. Selznick to cast her as Scarlett O'Hara in his 1939 production of Gone with the Wind. The film is a historical drama set during the reign of Elizabeth I focusing on England's victory over the Spanish Armada.

The Spanish Armada was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by the Alonso de Guzmán, Duke of Medina Sidonia, an aristocrat without previous naval experience appointed by Philip II of Spain. His orders were to sail up the English Channel, join with the Duke of Parma in Flanders, and escort an invasion force that would land in England and overthrow Elizabeth I. Its purpose was to reinstate Catholicism in England, end support for the Dutch Republic, and prevent attacks by English and Dutch privateers against Spanish interests in the Americas.

He blew with His winds, and they were scattered is a phrase used in the aftermath of the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, when the Spanish fleet was broken up by a storm, which was also called the Protestant Wind. The phrase seems to have had its origin in an inscription on one of the many commemorative medals struck to celebrate the occasion.

Katharine Basset was an English gentlewoman who served at the court of King Henry VIII, namely in the household of Queen Anne of Cleves, and was briefly jailed for speaking against him. Three of her letters to her mother Honor Grenville survive in the Lisle Papers.

Bonaventure was a 47-gun galleon purchased by the Royal Navy in 1567. She was the third vessel to bear the name. She was commanded by Sir Francis Drake during his 1587 attack on Cadiz, and a year later was part of the fleet to face the Spanish Armada.

The Golden Speech was delivered by Queen Elizabeth I of England in the Palace Council Chamber to 141 Members of the Commons, on 30 November 1601. It was a speech that was expected to address some pricing concerns, based on the recent economic issues facing the country. Ultimately, it proved to be her final address to Parliament and turned the mode of the speech to addressing the love and respect she had for the country, her position, and the Members themselves. It is reminiscent of her Speech to the Troops at Tilbury, which was given to English forces in preparation for the Spanish Armada's expected invasion. The Golden Speech has been taken to mark a symbolic end of Elizabeth's reign. Elizabeth died 16 months later in March 1603 and was succeeded by her first cousin twice removed, James I.

William Leigh (1550–1639) was a well-known English preacher, graduate of Oxford, the rector of St Wilfrid's Church, from 1586 until his death, and is presumed to have baptized Mayflower Pilgrim, Myles Standish. He is now remembered for his sermon series Queene Elizabeth paraleld from 1612, which includes the first published text record for the queen's speech to the troops at Tilbury in 1588.

On 21 April 1947, Princess Elizabeth, the heir presumptive to the British throne, gave a speech that was broadcast to the British Commonwealth on her 21st birthday. Elizabeth was accompanying her parents, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, on a tour of southern Africa. It was her first overseas tour.