Gram stain, is a method of staining used to classify bacterial species into two large groups: gram-positive bacteria and gram-negative bacteria. It may also be used to diagnose a fungal infection. The name comes from the Danish bacteriologist Hans Christian Gram, who developed the technique in 1884.

Gram-negative bacteria are bacteria that, unlike gram-positive bacteria, do not retain the crystal violet stain used in the Gram staining method of bacterial differentiation. Their defining characteristic is that their cell envelope consists of a thin peptidoglycan cell wall sandwiched between an inner (cytoplasmic) membrane and an outer membrane. These bacteria are found in all environments that support life on Earth.

Peptidoglycan or murein is a unique large macromolecule, a polysaccharide, consisting of sugars and amino acids that forms a mesh-like layer (sacculus) that surrounds the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane. The sugar component consists of alternating residues of β-(1,4) linked N-acetylglucosamine (NAG) and N-acetylmuramic acid (NAM). Attached to the N-acetylmuramic acid is an oligopeptide chain made of three to five amino acids. The peptide chain can be cross-linked to the peptide chain of another strand forming the 3D mesh-like layer. Peptidoglycan serves a structural role in the bacterial cell wall, giving structural strength, as well as counteracting the osmotic pressure of the cytoplasm. This repetitive linking results in a dense peptidoglycan layer which is critical for maintaining cell form and withstanding high osmotic pressures, and it is regularly replaced by peptidoglycan production. Peptidoglycan hydrolysis and synthesis are two processes that must occur in order for cells to grow and multiply, a technique carried out in three stages: clipping of current material, insertion of new material, and re-crosslinking of existing material to new material.

FtsZ is a protein encoded by the ftsZ gene that assembles into a ring at the future site of bacterial cell division. FtsZ is a prokaryotic homologue of the eukaryotic protein tubulin. The initials FtsZ mean "Filamenting temperature-sensitive mutant Z." The hypothesis was that cell division mutants of E. coli would grow as filaments due to the inability of the daughter cells to separate from one another. FtsZ is found in almost all bacteria, many archaea, all chloroplasts and some mitochondria, where it is essential for cell division. FtsZ assembles the cytoskeletal scaffold of the Z ring that, along with additional proteins, constricts to divide the cell in two.

In molecular biology and genetics, transformation is the genetic alteration of a cell resulting from the direct uptake and incorporation of exogenous genetic material from its surroundings through the cell membrane(s). For transformation to take place, the recipient bacterium must be in a state of competence, which might occur in nature as a time-limited response to environmental conditions such as starvation and cell density, and may also be induced in a laboratory.

The periplasm is a concentrated gel-like matrix in the space between the inner cytoplasmic membrane and the bacterial outer membrane called the periplasmic space in Gram-negative bacteria. Using cryo-electron microscopy it has been found that a much smaller periplasmic space is also present in Gram-positive bacteria, between cell wall and the plasma membrane. The periplasm may constitute up to 40% of the total cell volume of gram-negative bacteria, but is a much smaller percentage in gram-positive bacteria.

The cell envelope comprises the inner cell membrane and the cell wall of a bacterium. In Gram-negative bacteria an outer membrane is also included. This envelope is not present in the Mollicutes where the cell wall is absent.

The bacterial outer membrane is found in gram-negative bacteria. Gram-negative bacteria form two lipid bilayers in their cell envelopes - an inner membrane (IM) that encapsulates the cytoplasm, and an outer membrane (OM) that encapsulates the periplasm.

Filamentation is the anomalous growth of certain bacteria, such as Escherichia coli, in which cells continue to elongate but do not divide. The cells that result from elongation without division have multiple chromosomal copies.

A bacterium, despite its simplicity, contains a well-developed cell structure which is responsible for some of its unique biological structures and pathogenicity. Many structural features are unique to bacteria and are not found among archaea or eukaryotes. Because of the simplicity of bacteria relative to larger organisms and the ease with which they can be manipulated experimentally, the cell structure of bacteria has been well studied, revealing many biochemical principles that have been subsequently applied to other organisms.

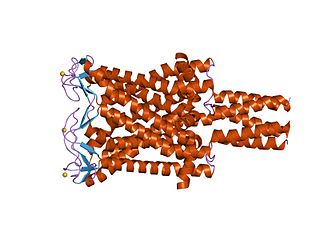

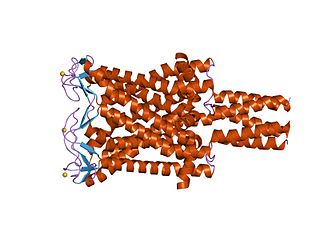

Large conductance mechanosensitive ion channels (MscLs) (TC# 1.A.22) are a family of pore-forming membrane proteins that are responsible for translating stresses at the cell membrane into an electrophysiological response. MscL has a relatively large conductance, 3 nS, making it permeable to ions, water, and small proteins when opened. MscL acts as stretch-activated osmotic release valve in response to osmotic shock.

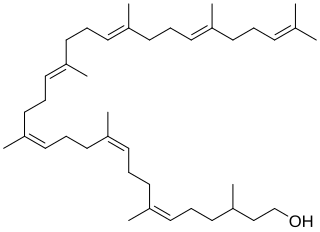

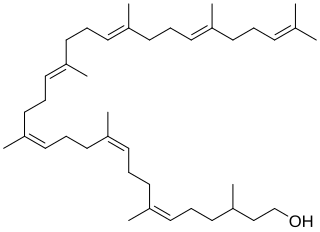

Bactoprenol also known as dolichol-11 and C55-isoprenyl alcohol (C55-OH) is a lipid first identified in certain species of lactobacilli. It is a hydrophobic alcohol that plays a key role in the growth of cell walls (peptidoglycan) in Gram-positive bacteria.

L-form bacteria, also known as L-phase bacteria, L-phase variants or cell wall-deficient bacteria (CWDB), are growth forms derived from different bacteria. They lack cell walls. Two types of L-forms are distinguished: unstable L-forms, spheroplasts that are capable of dividing, but can revert to the original morphology, and stable L-forms, L-forms that are unable to revert to the original bacteria.

Mechanosensitive channels (MSCs), mechanosensitive ion channels or stretch-gated ion channels are membrane proteins capable of responding to mechanical stress over a wide dynamic range of external mechanical stimuli. They are present in the membranes of organisms from the three domains of life: bacteria, archaea, and eukarya. They are the sensors for a number of systems including the senses of touch, hearing and balance, as well as participating in cardiovascular regulation and osmotic homeostasis (e.g. thirst). The channels vary in selectivity for the permeating ions from nonselective between anions and cations in bacteria, to cation selective allowing passage Ca2+, K+ and Na+ in eukaryotes, and highly selective K+ channels in bacteria and eukaryotes.

Small conductance mechanosensitive ion channels (MscS) provide protection against hypo-osmotic shock in bacteria, responding both to stretching of the cell membrane and to membrane depolarization. In eukaryotes, they fulfill a multitude of important functions in addition to osmoregulation. They are present in the membranes of organisms from the three domains of life: bacteria, archaea, fungi and plants.

Bacterial morphological plasticity refers to changes in the shape and size that bacterial cells undergo when they encounter stressful environments. Although bacteria have evolved complex molecular strategies to maintain their shape, many are able to alter their shape as a survival strategy in response to protist predators, antibiotics, the immune response, and other threats.

Lipid II is a precursor molecule in the synthesis of the cell wall of bacteria. It is a peptidoglycan, which is amphipathic and named for its bactoprenol hydrocarbon chain, which acts as a lipid anchor, embedding itself in the bacterial cell membrane. Lipid II must translocate across the cell membrane to deliver and incorporate its disaccharide-pentapeptide "building block" into the peptidoglycan mesh. Lipid II is the target of several antibiotics.

The potassium (K+) uptake permease (KUP) family (TC# 2.A.72) is a member of the APC superfamily of secondary carriers. Proteins of the KUP/HAK/KT family include the KUP (TrkD) protein of E. coli and homologues in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. High affinity (20 μM) K+ uptake systems (Hak1, TC# 2.A.72.2.1) of the yeast Debaryomyces occidentalis as well as the fungus, Neurospora crassa, and several homologues in plants have been characterized. Arabidopsis thaliana and other plants possess multiple KUP family paralogues. While many plant proteins cluster tightly together, the Hak1 proteins from yeast as well as the two Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial proteins are distantly related on the phylogenetic tree for the KUP family. All currently classified members of the KUP family can be found in the Transporter Classification Database.

The multidrug/oligosaccharidyl-lipid/polysaccharide (MOP) flippase superfamily is a group of integral membrane protein families. The MOP flippase superfamily includes twelve distantly related families, six for which functional data are available:

- One ubiquitous family (MATE) specific for drugs - (TC# 2.A.66.1) The Multi Antimicrobial Extrusion (MATE) Family

- One (PST) specific for polysaccharides and/or their lipid-linked precursors in prokaryotes - (TC# 2.A.66.2) The Polysaccharide Transport (PST) Family

- One (OLF) specific for lipid-linked oligosaccharide precursors of glycoproteins in eukaryotes - (TC# 2.A.66.3) The Oligosaccharidyl-lipid Flippase (OLF) Family

- One (MVF) lipid-peptidoglycan precursor flippase involved in cell wall biosynthesis - (TC# 2.A.66.4) The Mouse Virulence Factor (MVF) Family

- One (AgnG) which includes a single functionally characterized member that extrudes the antibiotic, Agrocin 84 - (TC# 2.A.66.5) The Agrocin 84 Antibiotic Exporter (AgnG) Family

- And finally, one (Ank) that shuttles inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) - (TC# 2.A.66.9) The Progressive Ankylosis (Ank) Family

Undecaprenyl phosphate (UP), also known lipid-P, bactoprenol and C55-P., is a molecule with the primary function of trafficking polysaccharides across the cell membrane, largely contributing to the overall structure of the cell wall in Gram-positive bacteria. In some situations, UP can also be utilized to carry other cell-wall polysaccharides, but UP is the designated lipid carrier for peptidoglycan. During the process of carrying the peptidoglycan across the cell membrane, N-acetylglucosamine and N-acetylmuramic acid are linked to UP on the cytoplasmic side of the membrane before being carried across. UP works in a cycle of phosphorylation and dephosphorylation as the lipid carrier gets used, recycled, and reacts with undecaprenyl phosphate. This type of synthesis is referred to as de novo synthesis where a complex molecule is created from simpler molecules as opposed to a complete recycle of the entire structure.