Related Research Articles

The American Revolution was a rebellion and political movement in the Thirteen Colonies which peaked when colonists initiated an ultimately successful war for independence against the Kingdom of Great Britain. Leaders of the American Revolution were colonial separatist leaders who originally sought more autonomy within the British political system as British subjects, but later assembled to support the Revolutionary War, which successfully ended British colonial rule over the colonies, establishing their independence, and leading to the creation of the United States of America.

The Stamp Act 1765, also known as the Duties in American Colonies Act 1765, was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain which imposed a direct tax on the British colonies in America and required that many printed materials in the colonies be produced on stamped paper from London which included an embossed revenue stamp. Printed materials included legal documents, magazines, playing cards, newspapers, and many other types of paper used throughout the colonies, and it had to be paid in British currency, not in colonial paper money.

The Intolerable Acts, sometimes referred to as the Insufferable Acts or Coercive Acts, were a series of five punitive laws passed by the British Parliament in 1774 after the Boston Tea Party. The laws aimed to punish Massachusetts colonists for their defiance in the Tea Party protest of the Tea Act, a tax measure enacted by Parliament in May 1773. In Great Britain, these laws were referred to as the Coercive Acts. They were a key development leading to the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War in April 1775.

The American Colonies Act 1766, commonly known as the Declaratory Act, was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain which accompanied the repeal of the Stamp Act 1765 and the amendment of the Sugar Act. Parliament repealed the Stamp Act because boycotts were hurting British trade and used the declaration to justify the repeal and avoid humiliation. The declaration stated that the Parliament's authority was the same in America as in Britain and asserted Parliament's authority to pass laws that were binding on the American colonies.

The Townshend Acts or Townshend Duties were a series of British acts of Parliament passed during 1767 and 1768 introducing a series of taxes and regulations to fund administration of the British colonies in America. They are named after the Chancellor of the Exchequer who proposed the programme. Historians vary slightly as to which acts they include under the heading "Townshend Acts", but five are often listed:

The Tea Act 1773 was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain. The principal objective was to reduce the massive amount of tea held by the financially troubled British East India Company in its London warehouses and to help the struggling company survive. A related objective was to undercut the price of illegal tea, smuggled into Britain's North American colonies. This was supposed to convince the colonists to purchase Company tea on which the Townshend duties were paid, thus implicitly agreeing to accept Parliament's right of taxation. Smuggled tea was a large issue for Britain and the East India Company, since approximately 86% of all the tea in America at the time was smuggled Dutch tea.

"No taxation without representation" is a political slogan that, though rooted in the Magna Carta, originated in its present form during the American Revolution and which expressed one of the primary grievances of the American colonists for Great Britain. In short, many colonists believed that as they were not represented in the distant British parliament, any taxes it imposed on the colonists were unconstitutional and were a denial of the colonists' rights as Englishmen.

A stamp act is any legislation that requires a tax to be paid on the transfer of certain documents. Those who pay the tax receive an official stamp on their documents, making them legal documents. A variety of products have been covered by stamp acts including playing cards, dice, patent medicines, cheques, mortgages, contracts, marriage licenses and newspapers. The items may have to be physically stamped at approved government offices following payment of the duty, although methods involving annual payment of a fixed sum or purchase of adhesive stamps are more practical and common.

The Massachusetts Circular Letter was a statement written by Samuel Adams and James Otis Jr., and passed by the Massachusetts House of Representatives in February 1768 in response to the Townshend Acts. Reactions to the letter brought heightened tensions between the British Parliament and Massachusetts, and resulted in the military occupation of Boston by the British Army, which contributed to the coming of the American Revolution.

The Daughters of Liberty was the formal female association that was formed in 1765 to protest the Stamp Act, and later the Townshend Acts, and was a general term for women who identified themselves as fighting for liberty during the American Revolution.

The Boston Tea Party was an American political and mercantile protest on December 16, 1773, by the Sons of Liberty in Boston in colonial Massachusetts. The target was the Tea Act of May 10, 1773, which allowed the East India Company to sell tea from China in American colonies without paying taxes apart from those imposed by the Townshend Acts. The Sons of Liberty strongly opposed the taxes in the Townshend Act as a violation of their rights. In response, the Sons of Liberty, some disguised as Native Americans, destroyed an entire shipment of tea sent by the East India Company.

The Chestertown Tea Party was a protest against British excise duties which, according to local legend, took place in May 1774 in Chestertown, Maryland as a response to the British Tea Act. Chestertown tradition holds that, following the example of the more famous Boston Tea Party, colonial patriots boarded the brigantine Geddes in broad daylight and threw its cargo of tea into the Chester River. The event is celebrated each Memorial Day weekend with a festival and historic reenactment called the Chestertown Tea Party Festival.

Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania is a series of essays written by the Pennsylvania lawyer and legislator John Dickinson (1732–1808) and published under the pseudonym "A Farmer" from 1767 to 1768. The twelve letters were widely read and reprinted throughout the Thirteen Colonies, and were important in uniting the colonists against the Townshend Acts in the run-up to the American Revolution. According to many historians, the impact of the Letters on the colonies was unmatched until the publication of Thomas Paine's Common Sense in 1776. The success of the letters earned Dickinson considerable fame.

Women in the American Revolution played various roles depending on their social status, race and political views.

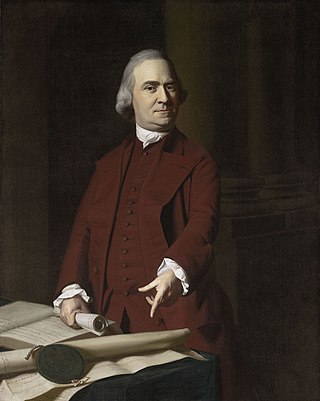

Samuel Adams was an American statesman, political philosopher, and a Founding Father of the United States. He was a politician in colonial Massachusetts, a leader of the movement that became the American Revolution, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and other founding documents, and one of the architects of the principles of American republicanism that shaped the political culture of the United States. He was a second cousin to his fellow Founding Father, President John Adams.

The Edenton Tea Party was a political protest in Edenton, North Carolina, in response to the Tea Act, passed by the British Parliament in 1773.

The Virginia Association was a series of non-importation agreements adopted by Virginians in 1769 as a way of speeding economic recovery and opposing the Townshend Acts. Initiated by George Washington, drafted by George Mason, and passed by the Virginia House of Burgesses in May 1769, the Virginia Association was a way for Virginians to stand united against continued British taxation and trade control. The Virginia Association served as the framework and precursor to the larger and more powerful 1774 Continental Association.

The Boston Non-importation agreement was an 18th century boycott that restricted importation of goods to the city of Boston. This agreement was signed on August 1, 1768 by more than 60 merchants and traders. After two weeks, there were only 16 traders who did not join the effort. In the upcoming months and years, this non-importation initiative was adopted by other cities: New York joined the same year, Philadelphia followed a year later. Boston stayed the leader in forming an opposition to the mother country and its taxing policy. The boycott lasted until the 1770 when the British Parliament repealed the acts against which the Boston Non-importation agreement was meant.

The 27 grievances is a section from the United States Declaration of Independence. The Second Continental Congress's Committee of Five drafted the document listing their grievances with the actions and decisions of King George III with regard to the Colonies in North America. The Second Continental Congress voted unanimously to adopt and issue the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776.

The homespun movement was started in 1767 by Quakers in Boston, Massachusetts, to encourage the purchase of goods, especially apparel, manufactured in the American Colonies. The movement was created in response to the British Townshend Acts of 1767 and 1768, in the early stages of the American Revolution.

References

- ↑ Berkin, Carol (2006). "It Was I Who Did It: Women's Role in the Founding of the Nation". Phi Kappa Phi Forum. 86: 15.

- 1 2 Salmon, Marylynn (2000). No Small Courage: A History of Women in The United States. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 135.

- 1 2 Salmon, Marylynn (2000). No Small Courage: A History of Women in The United States. Oxford: Oxford University. p. 136.

- ↑ Berkin, Carol (2006). "It Was I Who Did It: Women's Role in the Founding of the Nation". Phi Kappa Phi Forum. 86: 16.

- ↑ Macdonald, Anne (1988). No Idle Hands: The Social History of American Knitting. New York: Ballatine Books. pp. 80–81.

- ↑ Applewhite, Harriet B. (1993). Women and Politics in the Age of Democratic Revolution. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. p. 197.

- ↑ Peskin, Lawrence (2003). Manufacturing Revolution: The Intellectual Origins of Early American Industry. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 10–11.

- ↑ Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher (1998). "Wheels, Looms, and the Gendered Divisions of Labor in Eighteenth Century New England". The William and Mary Quarterly. 55 (1): 9. doi:10.2307/2674321. JSTOR 2674321.

- ↑ "Spinnstube" . Retrieved 4 April 2020.