Related Research Articles

The afterlife or life after death is a purported existence in which the essential part of an individual's stream of consciousness or identity continues to exist after the death of their physical body. The surviving essential aspect varies between belief systems; it may be some partial element, or the entire soul or spirit, which carries with it one's personal identity. Belief in an afterlife is in contrast to the belief in oblivion after death.

Christian eschatology, is a major branch of study within Christian theology, deals with the doctrine of the "last things", especially the Second Coming of Christ, or Parousia. Eschatology – the word derives from two Greek roots meaning "last" (ἔσχατος) and "study" (-λογία) – involves the study of "end things", whether of the end of an individual life, of the end of the age, of the end of the world, or of the nature of the Kingdom of God. Broadly speaking, Christian eschatology focuses on the ultimate destiny of individual souls and of the entire created order, based primarily upon biblical texts within the Old and New Testaments.

A devil is the personification of evil as it is conceived in various cultures and religious traditions. It is seen as the objectification of a hostile and destructive force. Jeffrey Burton Russell states that the different conceptions of the devil can be summed up as 1) a principle of evil independent from God, 2) an aspect of God, 3) a created being turning evil, and 4) a symbol of human evil.

In Catholic theology, Limbo is the afterlife condition of those who die in original sin without being assigned to the Hell of the Damned. Medieval theologians of Western Europe described the underworld as divided into three distinct parts: Hell of the Damned, Limbo of the Fathers or Patriarchs, and Limbo of the Infants. The Limbo of the Fathers is an official doctrine of the Catholic Church, but the Limbo of the Infants is not. The concept of Limbo comes from the idea that, in the case of Limbo of the Fathers, good people were not able to achieve heaven just because they were born before the birth of Jesus Christ. This is also true for Limbo of the Infants in that simply because a child died before baptism, does not mean they deserve punishment, though they cannot achieve salvation.

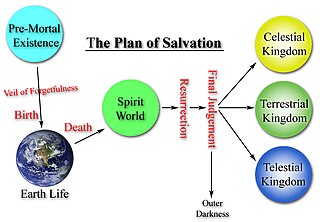

In Latter Day Saints theology, the term spirit world refers to the realm where the spirits of the dead await the resurrection. In LDS thought, this spirit world is divided into at least two conditions: Paradise and spirit prison:

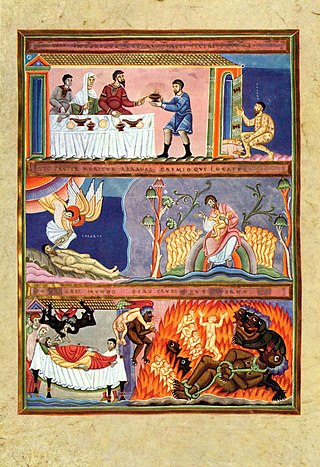

The Last Judgment, Final Judgment, Day of Reckoning, Day of Judgment, Judgment Day, Doomsday, Day of Resurrection or The Day of the Lord is a concept found across the Abrahamic religions and the Frashokereti of Zoroastrianism.

In Christian theology, the Harrowing of Hell is an Old English and Middle English term referring to the period of time between the Crucifixion of Jesus and his resurrection. In triumphant descent, Christ brought salvation to the souls held captive there since the beginning of the world.

Christian mortalism is the Christian belief that the human soul is not naturally immortal and may include the belief that the soul is "sleeping" after death until the Resurrection of the Dead and the Last Judgment, a time known as the intermediate state. "Soul sleep" is often used as a pejorative term, so the more neutral term "mortalism" was also used in the nineteenth century, and "Christian mortalism" since the 1970s. Historically the term psychopannychism was also used, despite problems with the etymology and application. The term thnetopsychism has also been used; for example, Gordon Campbell (2008) identified John Milton as believing in the latter.

In religion and folklore, hell is a location or state in the afterlife in which souls are subjected to punitive suffering, most often through torture, as punishment after death. Religions with a linear divine history often depict hells as eternal destinations, the biggest examples of which are Christianity and Islam, whereas religions with reincarnation usually depict a hell as an intermediary period between incarnations, as is the case in the Dharmic religions. Religions typically locate hell in another dimension or under Earth's surface. Other afterlife destinations include heaven, paradise, purgatory, limbo, and the underworld.

Particular judgment, according to Christian eschatology, is the divine judgment that a departed (dead) person undergoes immediately after death, in contradistinction to the general judgment of all people at the end of the world.

In Christian theology, Hell is the place or state into which, by God's definitive judgment, unrepentant sinners pass in the general judgment, or, as some Christians believe, immediately after death. Its character is inferred from teaching in the biblical texts, some of which, interpreted literally, have given rise to the popular idea of Hell. Theologians today generally see Hell as the logical consequence of rejecting union with God and with God's justice and mercy.

Hades, according to various Christian denominations, is "the place or state of departed spirits", borrowing the name of Hades, the Greek god of the underworld. It is often associated with the Jewish concept of Sheol.

In some forms of Christianity the intermediate state or interim state is a person's existence between death and the universal resurrection. In addition, there are beliefs in a particular judgment right after death and a general judgment or last judgment after the resurrection.

Thomas Tomkinson (1631–1710) was an English Muggletonian writer born at Ilam, near Dovedale, in Staffordshire. His parents, Richard and Ann, farmed at Sladehouse and Thomas took over the business as a yeoman farmer even while his father was alive. His faith was initially Presbyterian but in 1661 he read a book by Laurence Clarkson and became attracted to Muggletonianism. Earlier, in February 1652, he had had a revelatory experience similar to the one Lodowicke Muggleton reported in 1650 but without any experience of the direct voice of God which had come to John Reeve and which was the foundation experience of Muggletonianism. Since John Reeve died in 1658, these dates mean that Tomkinson was one of the first prominent Muggletonian personalities not to have known Reeve personally.

Purgatory is a passing intermediate state after physical death for purifying or purging a soul. A common analogy is dross being removed from metal in a furnace.

In Christianity, heaven is traditionally the location of the throne of God and the angels of God, and in most forms of Christianity it is the abode of the righteous dead in the afterlife. In some Christian denominations it is understood as a temporary stage before the resurrection of the dead and the saints' return to the New Earth.

A shaitan or shaytan is an evil spirit in Islam, inciting humans and the jinn to sin by "whispering" in their hearts. Although invisible to humans, shayāṭīn are imagined to be ugly and grotesque creatures created from Hellfire.

The Pillars of Adventism are landmark doctrines for Seventh-day Adventists. They are Bible doctrines that define who they are as a people of faith; doctrines that are "non-negotiables" in Adventist theology. The Seventh-day Adventist church teaches that these Pillars are needed to prepare the world for the second coming of Jesus Christ, and sees them as a central part of its own mission. Adventists teach that the Seventh-day Adventist Church doctrines were both a continuation of the reformation started in the 16th century and a movement of the end time rising from the Millerites, bringing God's final messages and warnings to the world.

Eternal life traditionally refers to continued life after death, as outlined in Christian eschatology. The Apostles' Creed testifies: "I believe... the resurrection of the body, and life everlasting." In this view, eternal life commences after the second coming of Jesus and the resurrection of the dead, although in the New Testament's Johannine literature there are references to eternal life commencing in the earthly life of the believer, possibly indicating an inaugurated eschatology.

Sijjin is in Islamic belief either a prison, vehement torment or straitened circumstances at the bottom of Jahannam or hell, below the earth, or, according to a different interpretation, a register for the damned or record of the wicked, which is mentioned in Quran 83:7. Sijjin is also considered to be a place for the souls of unbelievers until resurrection.

References

- ↑ Phædrus 249d-250c'" at mc.maricopa.edu website

- ↑ Bermon, Pascale (2013). Markus Vinzent (ed.). "Surviving the Disaster: The Use of Psyche in 1 Peter 3:20" (pdf). Studia Patristica . Leuven; Paris; Walpole, MA: Peeters Publishers. LXIII (11: Biblica Philosophica, Theologica, Ethica): 81, 84. Archived from the original on March 16, 2020. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- ↑ Leonhard Goppelt A Commentary on I Peter p254

- ↑ Thomas Belsham A calm inquiry into the Scripture doctrine concerning the person 1817 p106 "Christ was raised to life by the spirit, that is, the power of God : by which spirit, after he was gone to heaven, he preached by the ministry of his apostles to the spirits in prison, not to the dead, but to the Gentile world who were .."

- ↑ Grudem notes: "'St. Augustine, Letter 164, chs. 15–17; Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, part 3, question 52, art. 2, reply to obj. 3; Leighton, pp. 354–366; Zahn, p. 289; W. Kelly, Christ Preaching to the Spirits in Prison (London: Morrish 1872), pp. 3–89; DG Wohlenberg... etc.

- ↑ Hilarion Alfeyev, Christ the Conqueror of Hell: The descent into hades from an orthodox perspective, (St. Vladimirs:

- ↑ Bo Reicke The Disobedient Spirits & Christian Baptism: A Study of 1 Peter 3:19 and Its Context 1946

- ↑ The First Epistle of Peter: an introduction and commentary

- ↑ Stanley E. Porter, Michael A. Hayes, David Tombs Resurrection p110

- ↑ The Scripture view of Christ preaching to the spirits in prison p80 ".. he acted to " the spirits in prison ;" the persons interned in the Ark as in a place of protection. "

- ↑ Edward Hayes Plumptre The Spirits in Prison ch.1 Descent into Hades

- ↑ Lenski p169

- ↑ Porter, Resurrection p110

- ↑ F. Spitta, Christi Predigt an die Geister Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1890

- ↑ William Joseph Dalton Christ's proclamation to the spirits: a study of 1 Peter 3:18–4:6 p46 1989 "The pioneer of this new tendency, Spitta, remained to some degree within the Augustinian hypothesis. While he identified the spirits in prison with the rebellious angels who instigate the wickedness of the flood, he followed Augustine.."

- ↑ Edward Selwyn, The First Epistle of St. Peter (London: Macmillan, 1946)

- ↑ "موقع التفير الكبير".

- ↑ "موقع التفير الكبير".