Related Research Articles

Asia is home to hundreds of languages comprising several families and some unrelated isolates. The most spoken language families on the continent include Austroasiatic, Austronesian, Japonic, Dravidian, Indo-European, Afroasiatic, Turkic, Sino-Tibetan, Kra–Dai and Koreanic. Many languages of Asia, such as Chinese, Sanskrit, Arabic,Tamil or Telugu, have a long history as a written language.

Sinhala, sometimes called Sinhalese, is an Indo-Aryan language primarily spoken by the Sinhalese people of Sri Lanka, who make up the largest ethnic group on the island, numbering about 16 million. Sinhala is also spoken as the first language by other ethnic groups in Sri Lanka, totalling about 2 million speakers as of 2001. It is written using the Sinhala script, which is a Brahmic script closely related to the Grantha script of South India.

In addition to its classical and modern literary form, Malay had various regional dialects established after the rise of the Srivijaya empire in Sumatra, Indonesia. Also, Malay spread through interethnic contact and trade across the south East Asia Archipelago as far as the Philippines. That contact resulted in a lingua franca that was called Bazaar Malay or low Malay and in Malay Melayu Pasar. It is generally believed that Bazaar Malay was a pidgin, influenced by contact among Malay, Hokkien, Portuguese, and Dutch traders.

A pluricentric language or polycentric language is a language with several codified standard forms, often corresponding to different countries. Many examples of such languages can be found worldwide among the most-spoken languages, including but not limited to Chinese in mainland China, Taiwan and Singapore; English in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Ireland, South Africa, India, and elsewhere; and French in France, Canada, and elsewhere. The converse case is a monocentric language, which has only one formally standardized version. Examples include Japanese and Russian. In some cases, the different standards of a pluricentric language may be elaborated to appear as separate languages, e.g. Malaysian and Indonesian, Hindi and Urdu, while Serbo-Croatian is in an earlier stage of that process.

Islam is the third largest religion in Sri Lanka, with about 9.7 percent of the total population following the religion. About 1.9 million Sri Lankans adhere to Islam as per the Sri Lanka census of 2012. The majority of Muslims in Sri Lanka are concentrated in the Eastern Province of the island. Other areas containing significant Muslim minorities include the Western, Northwestern, North Central, Central and Sabaragamuwa provinces. Muslims form a large segment of the urban population of Sri Lanka and are mostly concentrated in major cities and large towns in Sri Lanka, like Colombo. Most Sri Lankan Muslims primarily speak Tamil, though it is not uncommon for Sri Lankan Muslims to be fluent in Sinhalese. The Sri Lankan Malays speak the Sri Lankan Malay creole language in addition to Sinhalese and Tamil.

Sri Lanka Indo-Portuguese, Ceylonese Portuguese Creole or Sri Lankan Portuguese Creole (SLPC) is a language spoken in Sri Lanka. While the predominant languages of the island are Sinhala and Tamil, the interaction of the Portuguese and the Sri Lankans led to the evolution of a new language, Sri Lanka Portuguese Creole (SLPC), which flourished as a lingua franca on the island for over 350 years (16th to mid-19th centuries). SLPC continues to be spoken by an unknown number of Sri Lankans, estimated to be extremely small.

Hambantota is the main town in Hambantota District, Southern Province, Sri Lanka.

Sri Lankan English (SLE) is the English language as it is used in Sri Lanka, a term dating from 1972. Sri Lankan English is principally categorised as the Standard Variety and the Nonstandard Variety, which is called as "Not Pot English". The classification of SLE as a separate dialect of English is controversial. English in Sri Lanka is spoken by approximately 23.8% of the population (2012 est.), and widely used for official and commercial purposes. Sri Lankan English being the native language of approximately 5,400 people thus challenges Braj Kachru's placement of it in the Outer Circle. Furthermore, it is taught as a compulsory second language in local schools from grade one to thirteen, and Sri Lankans pay special attention on learning English both as children and adults. It is considered even today that access and exposure to English from one's childhood in Sri Lanka is to be born with a silver spoon in one's mouth.

The Sri Lankan Tamil dialects or Ceylon Tamil or commonly in Tamil language Eelam Tamil are a group of Tamil dialects used in Sri Lanka by its native Tamil speakers that is distinct from the dialects of Tamil spoken in Tamil Nadu. It is broadly categorized into three sub groups: Jaffna Tamil, Batticaloa Tamil, and Negombo Tamil dialects. But there are a number of sub dialects within these broad regional dialects as well. These dialects are also used by ethnic groups other than Tamils and Muslims such as Sinhalese people, Portuguese Burghers and the indigenous Coastal Vedda people.

Sri Lankan Moors are an ethnic minority group in Sri Lanka, comprising 9.3% of the country's total population. Most of them are native speakers of the Tamil language. The majority of Moors who are not native to the North and East also speak Sinhalese as a second language. They are predominantly followers of Islam. The Sri Lankan Muslim community is mostly divided between Sri Lankan Moors, Indian Moors, Sri Lankan Malays and Sri Lankan Bohras. These groups are differentiated by lineage, language, history, culture and traditions.

Negombo Tamil dialect or Negombo Fishermen's Tamil is a Sri Lankan Tamil language dialect used by the fishers of Negombo, Sri Lanka. This is just one of the many dialects used by the remnant population of formerly Tamil speaking people of the western Puttalam District and Gampaha District of Sri Lanka. Those who still identify them as ethnic Tamils are known as Negombo Tamils or as Puttalam Tamils. Although most residents of these districts identify them as ethnic Sinhalese some are bilingual in both the languages.

The main languages spoken in Sri Lanka are Tamil and Sinhala. Several languages are spoken in Sri Lanka within the Indo-Aryan, Austronesian, and Dravidian families. Sri Lanka accords official status to Sinhala and Tamil, with English as a recognised language. The languages spoken on the island nation are deeply influenced by the various languages in India, Europe and Southeast Asia. Arab settlers and the colonial powers of Portugal, the Netherlands and Britain have also influenced the development of modern languages in Sri Lanka. See below for the most-spoken languages of Sri Lanka.

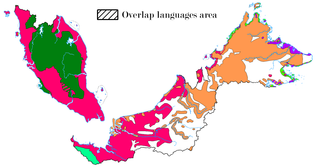

The indigenous languages of Malaysia belong to the Mon-Khmer and Malayo-Polynesian families. The national, or official, language is Malay which is the mother tongue of the majority Malay ethnic group. The main ethnic groups within Malaysia are the Malay people, Han Chinese people and Tamil people, with many other ethnic groups represented in smaller numbers, each with its own languages. The largest native languages spoken in East Malaysia are the Iban, Dusunic, and Kadazan languages. English is widely understood and spoken within the urban areas of the country; the English language is a compulsory subject in primary and secondary education. It is also the main medium of instruction within most private colleges and private universities. English may take precedence over Malay in certain official contexts as provided for by the National Language Act, especially in the states of Sabah and Sarawak, where it may be the official working language. Furthermore, the law of Malaysia is commonly taught and read in English, as the unwritten laws of Malaysia continue to be partially derived from pre-1957 English common law, which is a legacy of past British colonisation of the constituents forming Malaysia. In addition, authoritative versions of constitutional law and statutory law are continuously available in both Malay and English.

Vedda is an endangered language that is used by the indigenous Vedda people of Sri Lanka. Additionally, communities such as Coast Veddas and Anuradhapura Veddas who do not strictly identify as Veddas also use words from the Vedda language in part for communication during hunting and/or for religious chants, throughout the island.

Ja-Ela is a town, located approximately 20 km (12 mi) north of the city centre of Colombo, Sri Lanka. Ja-Ela lies on the A3 road which overlaps with the Colombo – Katunayake Expressway at the Ja-Ela Interchange.

Sri Lankan Malays are Sri Lankan citizens with full or partial ancestry from the Indonesian Archipelago, Malaysia, or Singapore. In addition, people from Brunei and the Philippines also consider themselves Malays.

The Dutch Burghers are an ethnic group in Sri Lanka, of mixed Dutch, Portuguese Burgher and Sri Lankan descent. However, they are a different community when compared with Portuguese Burghers. Originally an entirely Protestant community, many Burghers today remain Christian but belong to a variety of denominations. The Dutch Burghers of Sri Lanka speak English and the local languages Sinhala and Tamil.

Alamat Langkapuri was a Malay-language fortnightly publication in Jawi script, issued from Colombo, Ceylon. Alamat Lankapuri was first published in June 1869. It was the first Jawi script Malay-language newspaper printed worldwide. The newspaper was printed by lithograph.

There are many Tamil loanwords in other languages. The Tamil language, primarily spoken in southern India and Sri Lanka, has produced loanwords in many different languages, including Ancient Greek, Biblical Hebrew, English, Malay, native languages of Indonesia, Mauritian Creole, Tagalog, Russian, and Sinhala and Dhivehi.

References

- ↑ Sri Lankan Malay at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- 1 2 3 4 "APiCS Online - Survey chapter: Sri Lankan Malay". apics-online.info. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ↑ de Silva Jayasuriya, Shihan (2002). "Sri Lankan Malay: A Unique Creole" (PDF). NUSA: Linguistic studies of languages in and around Indonesia. 50: 43–57.

- 1 2 3 Mahroof, M. M. M. (1992). "Malay Language in Sri Lanka: Socio-mechanics of a Minority Language in Its Historical Setting". Islamic Studies. 31 (4): 463–478. ISSN 0578-8072. JSTOR 20840097.

- ↑ Jack Prentice (2010), "Manado Malay: Product and agent of language change", in Tom Dutton, Darrell T. Tryon (ed.), Language Contact and Change in the Austronesian World, Trends in Linguistics. Studies and Monographs [TiLSM] 77, Berlin–Boston: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 411–442, ISBN 978-3-11-088309-1, OCLC 853258768 , retrieved 19 September 2022

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Saldin, B. D. K. (27 May 2011). "Converting Sri Lankan Malay into a written language". The Island.

- ↑ Ansaldo, Umberto (2008). Harrison, K. David; Rood, David S.; Dwyer, Arienne (eds.). Sri Lanka Malay revisited: Genesis and classification. Typological Studies in Language 78. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 13–42. ISBN 978-90-272-2990-8.

- 1 2 Lim, Lisa; Ansaldo, Umberto (2006). "Keeping Kirinda vital: The endangerment-empowerment dilemma in the documentation of Sri Lanka Malay". Language and Communication Working Papers. 1: 51–66.

- ↑ Rassool, Romola (2015). Download citation of Examining responses to perceived 'endangerment' of the Sri Lanka Malay language and (re)-negotiating Sri Lanka Malay identity in a postcolonial context. Third Bremen Conference on Language and Literature in Colonial and Postcolonial Contexts, At Bremen, Germany.

- ↑ Citation error. See inline comment on how to fix it. [ verification needed ]

- ↑ Ansaldo, Umberto (2011). "Sri Lanka Malay and its Lankan adstrates". Typological Studies in Language. 95: 367–382. doi:10.1075/tsl.95.21ans. ISBN 978-90-272-0676-3.