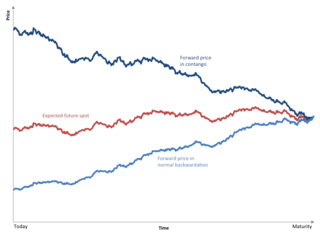

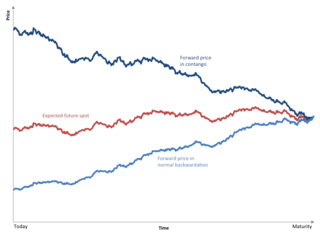

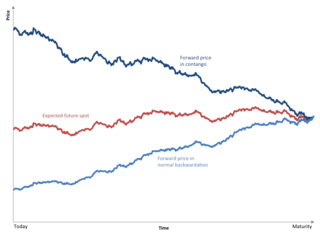

Normal backwardation, also sometimes called backwardation, is the market condition where the price of a commodity's forward or futures contract is trading below the expected spot price at contract maturity. The resulting futures or forward curve would typically be downward sloping, since contracts for further dates would typically trade at even lower prices. In practice, the expected future spot price is unknown, and the term "backwardation" may refer to "positive basis", which occurs when the current spot price exceeds the price of the future.

Contango is a situation where the futures price of a commodity is higher than the expected spot price of the contract at maturity. In a contango situation, arbitrageurs or speculators are "willing to pay more [now] for a commodity [to be received] at some point in the future than the actual expected price of the commodity [at that future point]. This may be due to people's desire to pay a premium to have the commodity in the future rather than paying the costs of storage and carry costs of buying the commodity today." On the other side of the trade, hedgers are happy to sell futures contracts and accept the higher-than-expected returns. A contango market is also known as a normal market, or carrying-cost market.

In finance, speculation is the purchase of an asset with the hope that it will become more valuable shortly.

Day trading is a form of speculation in securities in which a trader buys and sells a financial instrument within the same trading day, so that all positions are closed before the market closes for the trading day to avoid unmanageable risks and negative price gaps between one day's close and the next day's price at the open. Traders who trade in this capacity are generally classified as speculators. Day trading contrasts with the long-term trades underlying buy-and-hold and value investing strategies. Day trading may require fast trade execution, sometimes as fast as milli-seconds in scalping, therefore a direct-access day trading software is often needed.

In finance, a futures contract is a standardized legal contract to buy or sell something at a predetermined price for delivery at a specified time in the future, between parties not yet known to each other. The asset transacted is usually a commodity or financial instrument. The predetermined price of the contract is known as the forward price. The specified time in the future when delivery and payment occur is known as the delivery date. Because it derives its value from the value of the underlying asset, a futures contract is a derivative.

A futures exchange or futures market is a central financial exchange where people can trade standardized futures contracts defined by the exchange. Futures contracts are derivatives contracts to buy or sell specific quantities of a commodity or financial instrument at a specified price with delivery set at a specified time in the future. Futures exchanges provide physical or electronic trading venues, details of standardized contracts, market and price data, clearing houses, exchange self-regulations, margin mechanisms, settlement procedures, delivery times, delivery procedures and other services to foster trading in futures contracts. Futures exchanges can be organized as non-profit member-owned organizations or as for-profit organizations. Futures exchanges can be integrated under the same brand name or organization with other types of exchanges, such as stock markets, options markets, and bond markets. Non-profit member-owned futures exchanges benefit their members, who earn commissions and revenue acting as brokers or market makers. For-profit futures exchanges earn most of their revenue from trading and clearing fees.

A hedge is an investment position intended to offset potential losses or gains that may be incurred by a companion investment. A hedge can be constructed from many types of financial instruments, including stocks, exchange-traded funds, insurance, forward contracts, swaps, options, gambles, many types of over-the-counter and derivative products, and futures contracts.

In finance, cornering the market consists of obtaining sufficient control of a particular stock, commodity, or other asset in an attempt to manipulate the market price. One definition of cornering a market is "having the greatest market share in a particular industry without having a monopoly".

In finance, a contract for difference (CFD) is a legally binding agreement that creates, defines, and governs mutual rights and obligations between two parties, typically described as "buyer" and "seller", stipulating that the buyer will pay to the seller the difference between the current value of an asset and its value at contract time. If the closing trade price is higher than the opening price, then the seller will pay the buyer the difference, and that will be the buyer’s profit. The opposite is also true. That is, if the current asset price is lower at the exit price than the value at the contract’s opening, then the seller, rather than the buyer, will benefit from the difference.

Financial risk is any of various types of risk associated with financing, including financial transactions that include company loans in risk of default. Often it is understood to include only downside risk, meaning the potential for financial loss and uncertainty about its extent.

An energy derivative is a derivative contract based on an underlying energy asset, such as natural gas, crude oil, or electricity. Energy derivatives are exotic derivatives and include exchange-traded contracts such as futures and options, and over-the-counter derivatives such as forwards, swaps and options. Major players in the energy derivative markets include major trading houses, oil companies, utilities, and financial institutions.

The Dalian Commodity Exchange (DCE) is a Chinese futures exchange based in Dalian, Liaoning province, China. It is a non-profit, self-regulating and membership legal entity established on February 28, 1993.

The Shanghai Futures Exchange was formed from the amalgamation of the national level futures exchanges of China, the Shanghai Metal Exchange, Shanghai Foodstuffs Commodity Exchange, and the Shanghai Commodity Exchange in December 1999. It is a non-profit-seeking incorporated body regulated by the China Securities Regulatory Commission.

The 2000s commodities boom or the commodities super cycle was the rise of many physical commodity prices during the early 21st century (2000–2014), following the Great Commodities Depression of the 1980s and 1990s. The boom was largely due to the rising demand from emerging markets such as the BRIC countries, particularly China during the period from 1992 to 2013, as well as the result of concerns over long-term supply availability. There was a sharp down-turn in prices during 2008 and early 2009 as a result of the credit crunch and sovereign debt crisis, but prices began to rise as demand recovered from late 2009 to mid-2010.

The Sumitomo copper affair refers to a metal trading scandal in 1996 involving Yasuo Hamanaka, the chief copper trader of the Japanese trading house Sumitomo Corporation (Sumitomo). The scandal involves unauthorized trading over a 10-year period by Hamanaka, which led Sumitomo to announce US$1.8 billion in related losses in 1996 when Hamanaka's trading was discovered, and more related losses subsequently. The scandal also involved Hamanaka's attempts to corner the entire world's copper market through LME Copper futures contracts on the London Metal Exchange (LME).

Seasonal spread traders are spread traders that take advantage of seasonal patterns by holding long and short positions in futures contracts simultaneously in the same or a related commodity markets, such as the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, the New York Mercantile Exchange and the London Metal Exchange among others.

LME Aluminium stands for a group of spot, forward, and futures contracts, trading on the London Metal Exchange (LME), for delivery of primary Aluminium that can be used for price hedging, physical delivery of sales or purchases, investment, and speculation. Producers, semi-fabricators, consumers, recyclers, and merchants can use Aluminium futures contracts to hedge Aluminium price risks and to reference prices. Notable companies that use LME Aluminium contracts to hedge Aluminium prices include General Motors, Boeing, and Alcoa.

LME Copper stands for a group of spot, forward, and futures contracts, trading on the London Metal Exchange (LME), for delivery of Copper, that can be used for price hedging, physical delivery of sales or purchases, investment, and speculation.

LME Nickel stands for a group of spot, forward, and futures contracts, trading on the London Metal Exchange (LME), for delivery of primary Nickel that can be used for price hedging, physical delivery of sales or purchases, investment, and speculation. Producers, semi-fabricators, consumers, recyclers, and merchants can use Nickel futures contracts to hedge Nickel price risks and to reference prices. As of December 31, 2019, LME Nickel is associated with 153,318 tonnes of physical Nickel stored in 500 LME approved warehouses around the world. This is 5.67% of the 2019 global estimated mined Nickel production of 2.7 million tonnes. Despite the low share of physical Nickel associated with LME Nickel contracts, global physical Nickel transactions are usually based on LME Nickel prices. This practice began in the 1970s to 1982, when producer Nickel prices, especially Canadian producer prices collapsed, and the industry switched to LME prices.

LME Zinc stands for a group of spot, forward, and futures contracts, trading on the London Metal Exchange (LME), for delivery of special high-grade Zinc of 99.995% purity minimum that can be used for price hedging, physical delivery of sales or purchases, investment, and speculation. Producers, semi-fabricators, consumers, recyclers, and merchants can use Zinc futures contracts to hedge Zinc price risks and to reference prices.