Related Research Articles

Feminist economics is the critical study of economics and economies, with a focus on gender-aware and inclusive economic inquiry and policy analysis. Feminist economic researchers include academics, activists, policy theorists, and practitioners. Much feminist economic research focuses on topics that have been neglected in the field, such as care work, intimate partner violence, or on economic theories which could be improved through better incorporation of gendered effects and interactions, such as between paid and unpaid sectors of economies. Other feminist scholars have engaged in new forms of data collection and measurement such as the Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM), and more gender-aware theories such as the capabilities approach. Feminist economics is oriented towards the goal of "enhancing the well-being of children, women, and men in local, national, and transnational communities."

Childcare, otherwise known as day care, is the care and supervision of a child or multiple children at a time, whose ages range from two weeks of age to 18 years. Although most parents spend a significant amount of time caring for their child(ren), childcare typically refers to the care provided by caregivers that are not the child's parents. Childcare is a broad topic that covers a wide spectrum of professionals, institutions, contexts, activities, and social and cultural conventions. Early childcare is an important and often overlooked component of child development.

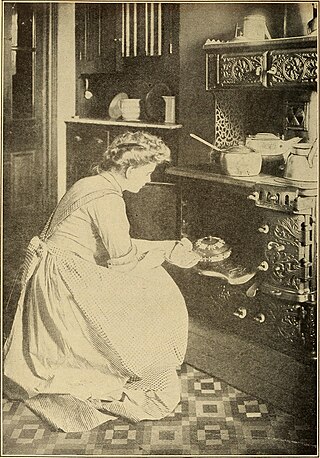

A housewife is a woman whose role is running or managing her family's home—housekeeping, which may include caring for her children; cleaning and maintaining the home; making, buying and/or mending clothes for the family; buying, cooking, and storing food for the family; buying goods that the family needs for everyday life; partially or solely managing the family budget—and who is not employed outside the home. The male equivalent is the househusband.

Babysitting is temporarily caring for a child. Babysitting can be a paid job for all ages; however, it is best known as a temporary activity for early teenagers who are not yet eligible for employment in the general economy. It provides autonomy from parental control and dispensable income, as well as an introduction to the techniques of childcare. It emerged as a social role for teenagers in the 1920s, and became especially important in suburban America in the 1950s and 1960s, when small children were abundant. It stimulated an outpouring of folk culture in the form of urban legends, pulp novels, and horror films.

A double burden is the workload of people who work to earn money, but who are also responsible for significant amounts of unpaid domestic labor. This phenomenon is also known as the Second Shift as in Arlie Hochschild's book of the same name. In couples where both partners have paid jobs, women often spend significantly more time than men on household chores and caring work, such as childrearing or caring for sick family members. This outcome is determined in large part by traditional gender roles that have been accepted by society over time. Labor market constraints also play a role in determining who does the bulk of unpaid work.

A stay-at-home dad is a father who is the main caregiver of the children and is generally the homemaker of the household. The female equivalent is the stay-at-home mom or housewife. As families have evolved, the practice of being a stay-at-home dad has become more common and socially acceptable. Pre-industrialization, the family worked together as a unit and was self-sufficient. When affection-based marriages emerged in the 1830s, parents began devoting more attention to children and family relationships became more open. Beginning with the Industrial Revolution, mass production replaced the manufacturing of home goods; this shift, coupled with prevailing norms governing sex or gender roles, dictated that the man become the breadwinner and the mother the caregiver of their children.

The sandwich generation is a group of middle-aged adults who care for both their aging parents and their own children. It is not a specific generation or cohort in the sense of the Greatest Generation or the Baby boomer generation, but a phenomenon that can affect anyone whose parents and children need support at the same time.

Nancy Folbre is an American feminist economist who focuses on economics and the family, non-market work and the economics of care. She is professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Carers' rights are rights of unpaid carers or caregivers to public recognition and assistance in preventing and alleviating problems arising from caring for relatives or friends with disabilities. The carers' rights movement draws attention to issues of low income, social exclusion, damage to mental and physical health identified by research into unpaid caregiving. In social policy and campaigning the movement distinguishes such people's situation from that of paid careworkers, who in most developed countries have the benefit of legal employment protection and rights at work. With an increasingly ageing population in all developed societies, the role of carer has been increasingly recognized as an important one, both functionally and economically. Many organizations which provide support for persons with disabilities have developed various forms of support for carers/caregivers as well.

Family caregivers are "relatives, friends, or neighbors who provide assistance related to an underlying physical or mental disability for at-home care delivery and assist in the activities of daily living (ADLs) who are unpaid and have no formal training to provide those services."

Unpaid labor or unpaid work is defined as labor or work that does not receive any direct remuneration. This is a form of non-market work which can fall into one of two categories: (1) unpaid work that is placed within the production boundary of the System of National Accounts (SNA), such as gross domestic product (GDP); and (2) unpaid work that falls outside of the production boundary, such as domestic labor that occurs inside households for their consumption. Unpaid labor is visible in many forms and isn't limited to activities within a household. Other types of unpaid labor activities include volunteering as a form of charity work and interning as a form of unpaid employment. In a lot of countries, unpaid domestic work in the household is typically performed by women, due to gender inequality and gender norms, which can result in high-stress levels in women attempting to balance unpaid work and paid employment. In poorer countries, this work is sometimes performed by children.

Care work is a sub-category of work that includes all tasks that directly involve the care processes done in service of others. It is often differentiated from other forms of work because it is considered to be intrinsically motivated. This perspective defines care labor as labor done out of affection or a sense of responsibility for other people, with no expectation of immediate pecuniary reward. Regardless of motivation, care work includes care activities done for pay as well as those done without remuneration.

A working parent is a father or a mother who engages in a work life. Contrary to the popular belief that work equates to efforts aside from parents' duties as a childcare provider and homemaker, it is thought that housewives or househusbands count as working parents. The variations of family structures include, but are not limited to, heterosexual couples where the father is the breadwinner and the mother keeps her duties focused within the home, homosexual parents who take on a range of work and home styles, single working mothers, and single working fathers. There are also married parents who are dual-earners, in which both parents provide income to support their family. Throughout the 20th century, family work structures experienced significant changes. This was shown by the range of work opportunities each parent was able to take and was expected to do, to fluctuations in wages, benefits, and time available to spend with children. These family structures sometimes raise much concern about gender inequalities. Within the institution of gender, there are defined gender roles that society expects of mothers and fathers that are reflected by events and expectations in the home and at work.

Work–family balance in the United States differs significantly for families of different social class. This differs from work–life balance: while work–life balance may refer to the health and living issues that arise from work, work–family balance refers specifically to how work and families intersect and influence each other.

Shared earning/shared parenting marriage, also known as peer marriage, is a type of marriage where partners at the outset agree to adhere to a model of shared responsibility for earning money, meeting the needs of children, doing household chores, and taking recreation time in near equal fashion across these four domains. It refers to an intact family formed in the relatively equal earning and parenting style from its initiation. Peer marriage is distinct from shared parenting, as well as the type of equal or co-parenting that father's rights activists in the United States, the United Kingdom and elsewhere seek after a divorce in the case of marriages, or unmarried pregnancies/childbirths, not set up in this fashion at the outset of the relationship or pregnancy.

The motherhood penalty is a term coined by sociologists, that in the workplace, working mothers encounter disadvantages in pay, perceived competence, and benefits relative to childless women. Specifically, women may suffer a per-child wage penalty, resulting in a pay gap between non-mothers and mothers that is larger than the gap between men and women. Mothers may also suffer worse job-site evaluations indicating that they are less committed to their jobs, less dependable, and less authoritative than non-mothers. Thus, mothers may experience disadvantages in terms of hiring, pay, and daily job experience. The motherhood penalty is not limited to one simple cause but can rather be linked to many theories and societal perceptions. However, one prominent theory that can be consistently linked to this penalty is the work-effort theory. It is also based on the mother's intersectionality. There are many effects developed from the motherhood penalty including wage, hiring, and promotion penalties. These effects are not limited to the United States and have been documented in over a dozen other industrialized nations including Japan, South Korea, The United Kingdom, The Netherlands, Poland, and Australia. The penalty has not shown any signs of declining over time.

A moneyless economy or nonmonetary economy is a system for allocation of goods and services without payment of money. The simplest example is the family household. Other examples include barter economies, gift economies and primitive communism.

Caregiving by country is the regional variation of caregiving practices as distinguished among countries.

Family policy in the country of Japan refers to government measures that attempt to increase the national birthrate in order to address Japan's declining population. It is speculated that leading causes of Japan's declining birthrate include the institutional and social challenges Japanese women face when expected to care for children while simultaneously working the long hours expected of Japanese workers. Japanese family policy measures therefore seek to make childcare easier for new parents.

Family Responsibilities Discrimination (FRD), also known as caregiver discrimination, is a form of employment discrimination toward workers who have caregiving responsibilities. Some examples of caregiver discrimination include changing an employee's schedule to conflict with their caregiving responsibilities, refusing to promote an employee, or refusing to hire an applicant.

References

- ↑ Narvaez, Darcia (2014). Neurobiology and the development of human morality: evolution, culture, and wisdom. The Norton series on interpersonal neurobiology. New York London: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-70655-0.

- ↑ "Key Concepts - Science of Child Development". Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. Retrieved 2024-05-06.

- ↑ Garner, Andrew; Yogman, Michael (August 1, 2021). "Preventing Childhood Toxic Stress: Partnering With Families and Communities to Promote Relational Health". Pediatrics. 148 (2).

- ↑ "Why Early Relational Health Matters". Nurture Connection. Retrieved 2024-05-06.

- ↑ de Marneffe, Daphne (May 14, 2019). Maternal Desire: On Children, Love, and the Inner Life. Scribner. ISBN 9781501198274.

- ↑ World, Kindred. "Kindred World". Kindred World. Retrieved 2024-05-06.

- ↑ Weaver, Meaghann; Nuemann, Marie; Lord, Blyth; Wiener, Lori; Lee, Junghyae; Hinds, Pamela (December 1, 2020). "Honoring the Good Parent Intentions of Courageous Parents: A Thematic Summary from a US-Based National Survey". Children. 7 (12).

- ↑ "Who's paying now?: The explicit and implicit costs of the current early care and education system". Economic Policy Institute. Retrieved 2024-05-06.

- ↑ Colyer, J. and National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services. (2023). Childcare Need and Availability in Rural Areas. Accessed April 9, 2024 https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hrsa/advisory-committees/rural/nac-rural-child-care-brief-23.pdf

- ↑ "How can I be a SAHM? I can't afford it.. - April 2022 Babies | Forums | What to Expect". community.whattoexpect.com. Retrieved 2024-05-06.

- ↑ Daminger, Allison, “The Cognitive Dimension of Household Labor,” American Sociological Review, 2019, vol. 84(4)609-633

- ↑ Hakim, Catherine (September 1, 2004). Key Issues in Women's Work: Female Diversity and the Polarisation of Women's Employment. Routledge-Cavendish. ISBN 9781904385165.

- ↑ Davis, Lisa (2024). Housewife: Why Women Still Do It All And What To Do Instead. New York: Legacy Lit. pp. XVIII. ISBN 978-1-5387-2288-6.

- 1 2 "Statistics on Mothers and Work: Setting the Record Straight | Family and Home Network". familyandhome.org. Retrieved 2024-05-06.

- ↑ "Labor force participation of mothers and fathers little changed in 2021, remains lower than in 2019 : The Economics Daily: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics". Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved 2024-05-06.

- 1 2 "Employment Characteristics of Families News Release - 2021 A01 Results". Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved 2024-05-06.

- ↑ How Moms Shape The World | Anna Malaika Tubbs | TED . Retrieved 2024-05-06– via www.youtube.com.

- ↑ "The World of Barilla Taylor: One Mill Girl's Experience in Lowell | UMass Lowell". www.uml.edu. Retrieved 2024-05-06.

- 1 2 3 Crittenden, Ann (2010). The Price of Motherhood: Why the Most Important Job in the World is Still the Least Valued. Picador. 10th Anniversary Edition: pages 65-66.

- ↑ "Household Production | U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA)". www.bea.gov. Retrieved 2024-05-06.

- ↑ Reid Boyd, E. and Letherby, G. eds. (2014) Stay-at-Home Mothers: Dialogues and Debates. Demeter Press, page 3.

- ↑ "Not all gaps are created equal: the true value of care work". Oxfam International. 2022-05-25. Retrieved 2024-05-06.

- ↑ Himmelweit, Susan (2002). "Making Visible the Hidden Economy: The Case for Gender-Impact Analysis of Economic Policy". Feminist Economics. 8 (1): 49–70. ISSN 1354-5701.

- ↑ Butt, Myrah Nerine; Shah, Saleha Kamal; Yahya, Fareeha Ali (2020-09-01). "Caregivers at the frontline of addressing the climate crisis". Gender & Development. 28 (3): 479–498. doi:10.1080/13552074.2020.1833482. ISSN 1355-2074.

- 1 2 "Campaign for Inclusive Family Policies | Family and Home Network". www.familyandhome.org. Retrieved 2024-05-06.

- ↑ "Revaluing Care in the Global Economy – Global Perspectives on Metrics, Governance, and Social Practices" . Retrieved 2024-05-06.

- ↑ "Home". The Center for Partnership Systems. Retrieved 2024-05-06.

- ↑ Nadasen, Premilla (2023). Care: the highest stage of capitalism. Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books. ISBN 978-1-64259-966-4. OCLC 1405607227.

- ↑ "Mothers At Home Matter". Mothers At Home Matter. 2024-05-07. Retrieved 2024-05-07.

- ↑ "Fédération Européenne Des Femmes Actives En Famille: About Us" . Retrieved May 6, 2024.

- ↑ Strike, Global Women's (2020-03-27). "Open letter to governments – a Care Income Now! - Global Women's Strike/ Wages for Housework/ Selma James" . Retrieved 2024-05-06.

- ↑ Strike, Global Women's (2021-01-23). "Endorsers to the Open Letter to Governments – A Care Income Now! - Global Women's Strike/ Wages for Housework/ Selma James" . Retrieved 2024-05-06.

- ↑ Minoff, Elisa; Coccia, Alex (March 2024). "Strategies to Compensate Unpaid Caregivers: A Policy Scan" (PDF). Center for the Study of Social Policy.

- ↑ "Parents Know Best: Giving Families a Choice in Childcare" (PDF). The Center for Social Justice. October 2022.

- ↑ "Early Childhood Matters 2023". Van Leer Foundation. 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2024-05-06.