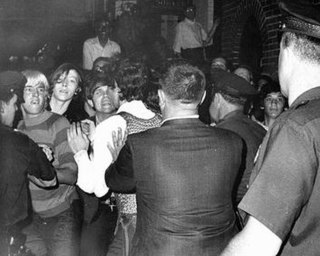

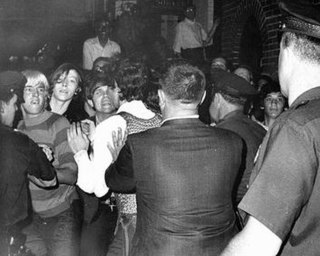

The Stonewall riots, also known as the Stonewall uprising, Stonewall rebellion, or simply Stonewall, were a series of protests by members of the LGBTQ community in response to a police raid that began in the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, at the Stonewall Inn in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Lower Manhattan in New York City. Patrons of the Stonewall, other Village lesbian and gay bars, trans activists and unhoused LGBT individuals fought back when the police became violent. The riots are widely considered the watershed event that transformed the gay liberation movement and the twentieth-century fight for LGBT rights in the United States.

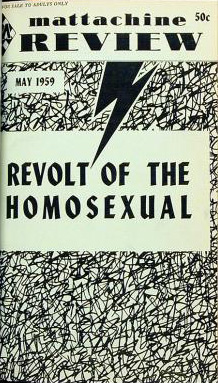

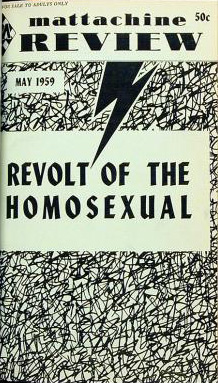

The Mattachine Society, founded in 1950, was an early national gay rights organization in the United States, preceded by several covert and open organizations, such as Chicago's Society for Human Rights. Communist and labor activist Harry Hay formed the group with a collection of male friends in Los Angeles to protect and improve the rights of gay men. Branches formed in other cities, and by 1961 the Society had splintered into regional groups.

Stonewall Equality Limited, trading as Stonewall, is a lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) rights charity in the United Kingdom. It is the largest LGBT rights organisation in Europe.

The Stonewall Inn is a gay bar and recreational tavern at 53 Christopher Street in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City. It was the site of the 1969 Stonewall riots, which led to the gay liberation movement and the modern fight for LGBT rights in the United States. When the riots occurred, Stonewall was one of a relative few gay bars in New York City. The original gay bar occupied two structures at 51–53 Christopher Street, which were built as horse stables in the 1840s.

Roland Emmerich is a German film director, screenwriter, and producer. He is widely known for his science fiction and disaster films and has been called a "master of disaster" within the industry. His films, most of which are English-language Hollywood productions, have made more than $3 billion worldwide, including just over $1 billion in the United States, making him the country's 15th-highest-grossing director of all time.

The gay liberation movement was a social and political movement of the late 1960s through the mid-1980s in the Western world, that urged lesbians and gay men to engage in radical direct action, and to counter societal shame with gay pride. In the feminist spirit of the personal being political, the most basic form of activism was an emphasis on coming out to family, friends, and colleagues, and living life as an openly lesbian or gay person.

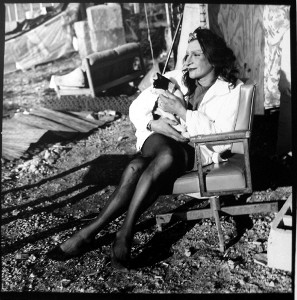

Sylvia Rivera was an American gay liberation and transgender rights activist who was also a noted community worker in New York. Rivera, who identified as a drag queen for most of her life and later as a transgender person, participated in demonstrations with the Gay Liberation Front.

Jon Robin Baitz is an American playwright, screenwriter and television producer. He is a two time Pulitzer Prize finalist, as well as a Guggenheim, American Academy of Arts and Letters, and National Endowment for the Arts Fellow.

Before Stonewall: The Making of a Gay and Lesbian Community is a 1984 American documentary film about the LGBT community prior to the 1969 Stonewall riots. It was narrated by author Rita Mae Brown, directed by Greta Schiller, co-directed by Robert Rosenberg, and co-produced by John Scagliotti and Rosenberg, and Schiller. It premiered at the 1984 Toronto International Film Festival and was released in the United States on June 27, 1985. In 1999, producer Scagliotti directed a companion piece, After Stonewall. To celebrate the 30th anniversary of the Teddy Awards, the film was shown at the 66th Berlin International Film Festival in February 2016. To commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots in 2019, the film was restored and re-released by First Run Features in June 2019. Later in 2019, the film was selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the United States National Film Registry for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Stonewall Uprising is a 2010 American documentary film examining the events surrounding the Stonewall riots that began during the early hours of June 28, 1969. Stonewall Uprising made its theatrical debut on June 16, 2010, at the Film Forum in New York City. The film features interviews with 15 participants and eyewitnesses to the riots, including many who were active in the uprising and later went on to form gay liberation groups, as well as law enforcement who participated in the raids that precipitated the rebellion.

Stormé DeLarverie was an American woman known as the butch lesbian whose scuffle with police was, according to DeLarverie and many eyewitnesses, the spark that ignited the Stonewall uprising, spurring the crowd to action. She was born in New Orleans, to an African American mother and a white father. She is remembered as a gay civil rights icon and entertainer, who performed and hosted at the Apollo Theater and Radio City Music Hall. She worked for much of her life as an MC, singer, bouncer, bodyguard, and volunteer street patrol worker, the "guardian of lesbians in the Village." She is known as "the Rosa Parks of the gay community."

LGBT history in the United States spans the contributions and struggles of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people, as well as the LGBT social movements they have built.

Edward George Skrein is an English actor, filmmaker, and rapper. He rose to recognition as the villain Francis Freeman / Ajax in the superhero comedy film Deadpool (2016). He also starred in the films The Transporter: Refueled (2015), Alita: Battle Angel (2019), Midway (2019), Rebel Moon – Part One: A Child of Fire (2023) and Rebel Moon – Part Two: The Scargiver (2024).

The National LGBTQ Task Force is an American social justice advocacy non-profit organizing the grassroots power of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) community. Also known as The Task Force, the organization supports action and activism on behalf of LGBTQ people and advances a progressive vision of liberation. The past executive director was Rea Carey from 2008-2021 and the current executive director is Kierra Johnson, who took over the position in 2021 to become the first Black woman to head the organization.

The Gay Liberation Monument is part of the Stonewall National Monument, which commemorates the Stonewall uprising of 1969. Created in 1980, the Gay Liberation sculpture by American artist George Segal was the first piece of public art dedicated to gay rights and solidarity for LGBT individuals, while simultaneously commemorating the ongoing struggles of the community. The monument was dedicated on June 23, 1992, as part of the dedication of the Stonewall National Monument as a whole.

New York City has been described as the gay capital of the world and the central node of the LGBTQ+ sociopolitical ecosystem, and is home to one of the world's largest and most prominent LGBTQ+ populations. Brian Silverman, the author of Frommer's New York City from $90 a Day, wrote the city has "one of the world's largest, loudest, and most powerful LGBT communities", and "Gay and lesbian culture is as much a part of New York's basic identity as yellow cabs, high-rise buildings, and Broadway theatre". LGBT travel guide Queer in the World states, "The fabulosity of Gay New York is unrivaled on Earth, and queer culture seeps into every corner of its five boroughs". LGBT advocate and entertainer Madonna stated metaphorically, "Anyways, not only is New York City the best place in the world because of the queer people here. Let me tell you something, if you can make it here, then you must be queer."

Happy Birthday, Marsha! is a 2017 fictional short film that imagines the gay and transgender rights pioneers Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera in the hours that led up to the 1969 Stonewall riots in New York City. The film stars Mya Taylor as Johnson and Eve Lindley as Rivera.

On August 5, 1969, the Atlanta Police Department led a police raid on a screening of the film Lonesome Cowboys at a movie theater in Atlanta, Georgia, United States.

Carsten H.W. Lorenz, known professionally as Carsten Lorenz, is a German film producer. He is best known for his work as a regular collaborator of director Roland Emmerich.

LGBT Pride Month, often shortened to Pride Month, is a month, typically June, dedicated to celebration and commemoration of lesbian, gay, bisexual, asexual and transgender (LGBT) pride. Pride Month began after the Stonewall riots, a series of gay liberation protests in 1969.