Blackface is the practice of non-black performers using burnt cork or theatrical makeup to portray a caricature of black people on stage or in entertainment.

The minstrel show, also called minstrelsy, was an American form of theater developed in the early 19th century. The shows were performed by mostly white actors wearing blackface makeup for the purpose of comically portraying racial stereotypes of African Americans. There were also some African-American performers and black-only minstrel groups that formed and toured. Minstrel shows stereotyped blacks as dimwitted, lazy, buffoonish, cowardly, superstitious, and happy-go-lucky. Each show consisted of comic skits, variety acts, dancing, and music performances that depicted people specifically of African descent.

Christy's Minstrels, sometimes referred to as the Christy Minstrels, were a blackface group formed by Edwin Pearce Christy, a well-known ballad singer, in 1843, in Buffalo, New York. They were instrumental in the solidification of the minstrel show into a fixed three-act form. The troupe also invented or popularized "the line", the structured grouping that constituted the first act of the standardized three-act minstrel show, with the interlocutor in the middle and "Mr. Tambo" and "Mr. Bones" on the ends.

The Ethiopian Serenaders was an American blackface minstrel troupe successful in the 1840s and 1850s. Through various line-ups they were managed and directed by James A. Dumbolton (c.1808–?), and are sometimes mentioned as the Boston Minstrels, Dumbolton Company or Dumbolton's Serenaders.

Madame Rentz's Female Minstrels was a blackface minstrel troupe composed completely of women. M. B. Leavitt founded the company in 1870. Unlike mainstream minstrelsy at the time, Leavitt's cast was entirely made up of women, whose primary role was to showcase their scantily clad bodies and tights, not the traditional role of comedy routines or song and dance numbers. The women still performed a basic minstrel show, but they added new pieces that titillated the audience. John E. Henshaw, who began his career as a stage hand with Madame Rentz's Female Minstrels, recalled,

"In San Francisco, we had advertised that we were going to put on the can-can. Mabel Santley did this number and when the music came to the dum-de-dum, she raised her foot just about twelve inches; whereupon the entire audience hollored [sic] 'Whooooo!' It set them crazy."

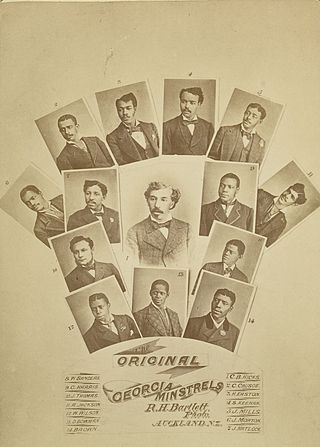

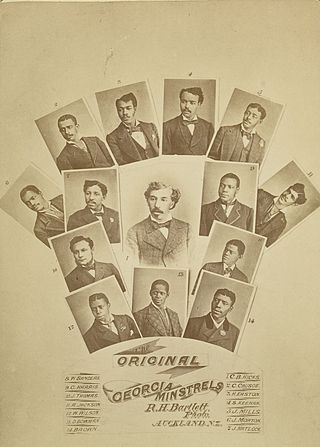

Charles Callender was the owner of blackface minstrel troupes that featured African American performers. Although a tavern owner by trade, he entered show business in 1872 when he purchased Sam Hague's Slave Troupe of Georgia Minstrels.

Sam Hague was a British blackface minstrel dancer and troupe owner. He was a pioneering white owner of a minstrel troupe composed of black members, and the success he saw with this troupe inspired many other white minstrel managers to tour with black companies.

Francis Leon (born Francis Patrick Glassey; November 21, 1844 – August 19, 1922 was an American vaudevillian actor best known as a blackface minstrel performer and female impersonator. He was largely responsible for making the prima donna a fixture of blackface minstrelsy.

Primrose and West was an American blackface song-and-dance team made up of partners George Primrose and William H. "Billy" West. They later went into the business of minstrel troupe ownership with a refined, high-class approach that signaled the final stage in the development of minstrelsy as a distinct form of entertainment.

Brooker and Clayton's Georgia Minstrels was the first popular African American blackface minstrel troupe. The company was formed in 1865. Under the management of Charles Hicks, the company enjoyed success on tour through the Northeastern United States in 1865 and 1866. They billed themselves as "The Only Simon Pure Negro Troupe in the World" and their act as an "authentic" portrayal of black plantation life. One ad claimed their troupe was "composed of men who during the war were SLAVES IN MACON, GEORGIA, who, having spent their former lives in Bondage. .. will introduce to their patrons PLANTATION LIFE in all its phases." For their part, the public and press largely believed them. One New York newspaper called them "great delineators of darky life" and said that they presented "peculiar music and characteristics of plantation life."

Bryant's Minstrels was a blackface minstrel troupe that performed in the mid-19th century, primarily in New York City. The troupe was led by the O'Neill brothers from upstate New York, who took the stage name Bryant.

"Ole Bull and Old Dan Tucker" is a traditional American song. Several different versions are known, the earliest published in 1844 by the Boston-based Charles Keith company. The song's lyrics tell of the rivalry and contest of skill between Ole Bull and Dan Tucker. The song also satirizes the low pay earned by early minstrel performers: "Ole Bull come to town one day [and] got five hundred for to play."

"Walk Along John", also known as "Oh, Come Along John", is an American song written for the blackface minstrel show stage in 1843. The lyrics of the song are typical of those of the early minstrel show. They are largely nonsense about a black man who boasts about his exploits.

"Miss Lucy Long", also known as "Lucy Long" as well as by other variants, is an American song that was popularized in the blackface minstrel show.

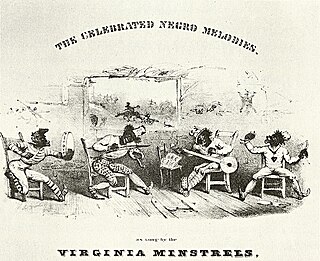

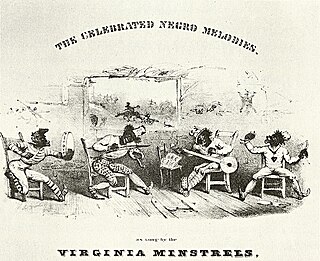

George B. Wooldridge was the business manager of the first blackface minstrel troupe, the Virginia Minstrels, in the mid-19th century. He sometimes went by the name Tom Quick.

Francis Marion Brower was an American blackface performer active in the mid-19th century. Brower began performing blackface song-and-dance acts in circuses and variety shows when he was 13. He eventually introduced the bones to his act, helping to popularize it as a blackface instrument. Brower teamed with various other performers, forming his longest association with banjoist Dan Emmett beginning in 1841. Brower earned a reputation as a gifted dancer. In 1842, Brower and Emmett moved to New York City. They were out of work by January 1843, when they teamed up with Billy Whitlock and Richard Pelham to form the Virginia Minstrels. The group was the first to perform a full minstrel show as a complete evening's entertainment. Brower pioneered the role of the endman.

John Diamond, aka Jack or Johnny, was an Irish-American dancer and blackface minstrel performer. Diamond entered show business at age 17 and soon came to the attention of circus promoter P. T. Barnum. In less than a year, Diamond and Barnum had a falling-out, and Diamond left to perform with other blackface performers. Diamond's dance style merged elements of English, Irish, and African dance. For the most part, he performed in blackface and sang popular minstrel tunes or accompanied a singer or instrumentalist. Diamond's movements emphasized lower-body movements and rapid footwork with little movement above the waist.

Luke Schoolcraft was an American minstrel music composer and performer. He appeared in numerous minstrel shows throughout the North after the American Civil War.

George H. Coes was an American minstrel music performer. He appeared in numerous minstrel shows in California and throughout the Northeastern United States.