Dishonoured cheques are cheques that a bank on which is drawn declines to pay (“honour”). There are a number of reasons why a bank would refuse to honour a cheque, with non-sufficient funds (NSF) being the most common one, indicating that there are insufficient cleared funds in the account on which the cheque was drawn. An NSF check may be referred to as a bad check, dishonored check, bounced check, cold check, rubber check, returned item, or hot check. Lost or bounced checks result in late payments and affect the relationship with customers. In England and Wales and Australia, such cheques are typically returned endorsed "Refer to drawer", an instruction to contact the person issuing the cheque for an explanation as to why it was not paid. If there are funds in an account, but insufficient cleared funds, the cheque is normally endorsed “Present again”, by which time the funds should have cleared.

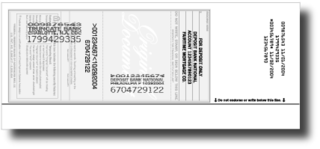

Magnetic ink character recognition code, known in short as MICR code, is a character recognition technology used mainly by the banking industry to streamline the processing and clearance of cheques and other documents. MICR encoding, called the MICR line, is at the bottom of cheques and other vouchers and typically includes the document-type indicator, bank code, bank account number, cheque number, cheque amount and a control indicator. The format for the bank code and bank account number is country-specific.

Cheque clearing or bank clearance is the process of moving cash from the bank on which a cheque is drawn to the bank in which it was deposited, usually accompanied by the movement of the cheque to the paying bank, either in the traditional physical paper form or digitally under a cheque truncation system. This process is called the clearing cycle and normally results in a credit to the account at the bank of deposit, and an equivalent debit to the account at the bank on which it was drawn, with a corresponding adjustment of accounts of the banks themselves. If there are not enough funds in the account when the cheque arrived at the issuing bank, the cheque would be returned as a dishonoured cheque marked as non-sufficient funds.

In the United States, an ABA routing transit number is a nine-digit code printed on the bottom of checks to identify the financial institution on which it was drawn. The American Bankers Association (ABA) developed the system in 1910 to facilitate the sorting, bundling, and delivering of paper checks to the drawer's bank for debit to the drawer's account.

The Check Clearing for the 21st Century Act is a United States federal law, Pub. L. 108–100 (text)(PDF), that was enacted on October 28, 2003 by the 108th U.S. Congress. The Check 21 Act took effect one year later on October 28, 2004. The law allows the recipient of the original paper check to create a digital version of the original check, a process known as check truncation, into an electronic format called a "substitute check", thereby eliminating the need for further handling of the physical document. In essence, the recipient bank no longer returns the paper check, but effectively e-mails an image of both sides of the check to the bank it is drawn upon.

Cheque fraud, or check fraud, refers to a category of criminal acts that involve making the unlawful use of cheques in order to illegally acquire or borrow funds that do not exist within the account balance or account-holder's legal ownership. Most methods involve taking advantage of the float to draw out these funds. Specific kinds of cheque fraud include cheque kiting, where funds are deposited before the end of the float period to cover the fraud, and paper hanging, where the float offers the opportunity to write fraudulent cheques but the account is never replenished.

The Australian financial system consists of the arrangements covering the borrowing and lending of funds and the transfer of ownership of financial claims in Australia, comprising:

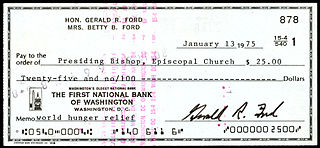

A cheque, or check, is a document that orders a bank to pay a specific amount of money from a person's account to the person in whose name the cheque has been issued. The person writing the cheque, known as the drawer, has a transaction banking account where the money is held. The drawer writes various details including the monetary amount, date, and a payee on the cheque, and signs it, ordering their bank, known as the drawee, to pay the amount of money stated to the payee.

In banking and finance, clearing denotes all activities from the time a commitment is made for a transaction until it is settled. This process turns the promise of payment into the actual movement of money from one account to another. Clearing houses were formed to facilitate such transactions among banks.

A payment system is any system used to settle financial transactions through the transfer of monetary value. This includes the institutions, payment instruments such as payment cards, people, rules, procedures, standards, and technologies that make its exchange possible. A common type of payment system, called an operational network, links bank accounts and provides for monetary exchange using bank deposits. Some payment systems also include credit mechanisms, which are essentially a different aspect of payment.

In banking, a post-dated cheque is a cheque written by the drawer (payer) for a date in the future.

Remote deposit or mobile deposit is the ability of a bank customer to deposit a cheque into a bank account from a remote location, without having to physically deliver the cheque to the bank. This was originally accomplished by scanning a digital image of a cheque into a computer then transmitting that image to the bank, but is now accomplished with a smartphone. The practice became legal in the United States in 2004 when the Check Clearing for the 21st Century Act took effect, though banks are not required to implement the system.

In banking, a lockbox is a service offered to organizations by commercial banks to simplify collection and processing of accounts receivable by having those organizations' customers' payments mailed directly to a location accessible by the bank.

Bank regulation in the United States is highly fragmented compared with other G10 countries, where most countries have only one bank regulator. In the U.S., banking is regulated at both the federal and state level. Depending on the type of charter a banking organization has and on its organizational structure, it may be subject to numerous federal and state banking regulations. Apart from the bank regulatory agencies the U.S. maintains separate securities, commodities, and insurance regulatory agencies at the federal and state level, unlike Japan and the United Kingdom. Bank examiners are generally employed to supervise banks and to ensure compliance with regulations.

In financial transactions, a warrant is a written order by one person that instructs or authorises another person to pay a specified recipient a specific amount of money or supply goods at a specific date. A warrant may or may not be negotiable and may be a bearer instrument that authorises payment to the warrant holder on demand or after a specific date. Governments and businesses may pay wages and other accounts by issuing warrants instead of cheques.

Cheque truncation is a cheque clearance system that involves the digitization of a physical paper cheque into a substitute electronic form for transmission to the paying bank. The process of cheque clearance, involving data matching and verification, is done using digital images instead of paper copies.

The Clearing House is a banking association and payments company owned by the largest commercial banks in the United States. The Clearing House is the parent organization of The Clearing House Payments Company L.L.C., which owns and operates core payments system infrastructure in the United States, including ACH, wire payments, check image clearing, and real-time payments through the RTP network, a modern real-time payment system for the U.S.

Cheque Truncation System (CTS) or Image-based Clearing System (ICS), in India, is a project of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), commenced in 2010, for faster clearing of cheques. CTS is based on a cheque truncation or online image-based cheque clearing system where cheque images and magnetic ink character recognition (MICR) data are captured at the collecting bank branch and transmitted electronically.

A substitute check or cheque, also called an image cash letter (ICL), clearing replacement document (CRD), or image replacement document (IRD), is a negotiable instrument used in electronic banking systems to represent a physical paper cheque (check). It may be wholly digital from payment initiation to clearing and settlement or it may be a digital reproduction (truncation) of an original paper check.

In the United States, remotely created checks are orders of payment created by the payee using a telephone or the Internet.