Related Research Articles

Self-harm is intentional behavior that is considered harmful to oneself. This is most commonly regarded as direct injury of one's own skin tissues usually without a suicidal intention. Other terms such as cutting, self-injury, and self-mutilation have been used for any self-harming behavior regardless of suicidal intent. Common forms of self-harm include damaging the skin with a sharp object or by scratching, hitting, or burning. The exact bounds of self-harm are imprecise, but generally exclude tissue damage that occurs as an unintended side-effect of eating disorders or substance abuse, as well as societally acceptable body modification such as tattoos and piercings.

Suicide is the second leading cause of death for people in the United States from the ages of 9 to 56.

Suicide prevention is a collection of efforts to reduce the risk of suicide. Suicide is often preventable, and the efforts to prevent it may occur at the individual, relationship, community, and society level. Suicide is a serious public health problem that can have long-lasting effects on individuals, families, and communities. Preventing suicide requires strategies at all levels of society. This includes prevention and protective strategies for individuals, families, and communities. Suicide can be prevented by learning the warning signs, promoting prevention and resilience, and committing to social change.

Suicide intervention is a direct effort to prevent a person or persons from attempting to take their own life or lives intentionally.

Suicidal ideation, or suicidal thoughts, is the thought process of having ideas, or ruminations about the possibility of ending one's own life. It is not a diagnosis but is a symptom of some mental disorders, use of certain psychoactive drugs, and can also occur in response to adverse life events without the presence of a mental disorder.

Suicidology is the scientific study of suicidal behaviour, the causes of suicidalness and suicide prevention. Every year, about one million people die by suicide, which is a mortality rate of sixteen per 100,000 or one death every forty seconds. Suicidologists believe that suicide is largely preventable with the right actions, knowledge about suicide, and a change in society's view of suicide to make it more acceptable to talk about suicide. There are many different fields and disciplines involved with suicidology, the two primary ones being psychology and sociology.

Suicide risk assessment is a process of estimating the likelihood for a person to attempt or die by suicide. The goal of a thorough risk assessment is to learn about the circumstances of an individual person with regard to suicide, including warning signs, risk factors, and protective factors. Risk for suicide is re-evaluated throughout the course of care to assess the patient's response to personal situational changes and clinical interventions. Accurate and defensible risk assessment requires a clinician to integrate a clinical judgment with the latest evidence-based practice, although accurate prediction of low base rate events, such as suicide, is inherently difficult and prone to false positives.

A suicide crisis, suicidal crisis or potential suicide is a situation in which a person is attempting to kill themselves or is seriously contemplating or planning to do so. It is considered by public safety authorities, medical practice, and emergency services to be a medical emergency, requiring immediate suicide intervention and emergency medical treatment. Suicidal presentations occur when an individual faces an emotional, physical, or social problem they feel they cannot overcome and considers suicide to be a solution. Clinicians usually attempt to re-frame suicidal crises, point out that suicide is not a solution and help the individual identify and solve or tolerate the problems.

Youth suicide is when a young person, generally categorized as someone below the legal age of majority, deliberately ends their own life. Rates of youth suicide and attempted youth suicide in Western societies and other countries are high. Youth suicide attempts are more common among girls, but adolescent males are the ones who usually carry out suicide. Suicide rates in youths have nearly tripled between the 1960s and 1980s. For example, in Australia suicide is second only to motor vehicle accidents as its leading cause of death for people aged 15 to 25.

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders, physical disorders, and substance abuse are risk factors. Some suicides are impulsive acts due to stress, relationship problems, or harassment and bullying. Those who have previously attempted suicide are at a higher risk for future attempts. Effective suicide prevention efforts include limiting access to methods of suicide such as firearms, drugs, and poisons; treating mental disorders and substance abuse; careful media reporting about suicide; and improving economic conditions. Although crisis hotlines are common resources, their effectiveness has not been well studied.

Self-embedding is the insertion of foreign objects either into soft tissues under the skin or into muscle. Self-embedding is typically considered deliberate self-harm, also known as nonsuicidal self-injury, which is defined as "deliberate, direct destruction of tissues without suicidal intent."

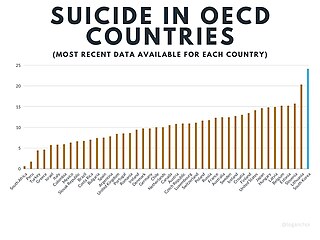

Suicide in South Korea occurs at the 12th highest rate in the world. South Korea has the highest recorded suicide rate in the OECD. In South Korea, it is estimated to affect 0.02 percent of the population by the WHO. In 2012, suicide was the fourth-highest cause of death. The suicide rate has consistently declined between 2012 and 2019, the year when the latest data are available.

IS PATH WARM? is an acronym utilized as a mnemonic device. It was created by the American Association of Suicidology to help counselors and the general public "remember the warning signs of suicide."

A suicide attempt is an act in which an individual tries to die by suicide but survives. While it may be described as a "failed" or "unsuccessful" suicide attempt, mental health professionals discourage the use of these terms as they imply that a suicide resulting in death is a successful or desirable outcome.

Vehicular suicide is the use of a motor vehicle to intentionally cause one's own death.

Researchers study Social media and suicide to find if a correlation exists between the two. Some research has shown that there may be a correlation.

The Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale, or C-SSRS, is a suicidal ideation and behavior rating scale created by researchers at Columbia University, University of Pennsylvania, University of Pittsburgh and New York University to evaluate suicide risk. It rates an individual's degree of suicidal ideation on a scale, ranging from "wish to be dead" to "active suicidal ideation with specific plan and intent and behaviors." Questions are phrased for use in an interview format, but the C-SSRS may be completed as a self-report measure if necessary. The scale identifies specific behaviors which may be indicative of an individual's intent to kill oneself. An individual exhibiting even a single behavior identified by the scale was 8 to 10 times more likely to die by suicide.

The interpersonal theory of suicide attempts to explain why individuals engage in suicidal behavior and to identify individuals who are at risk. It was developed by Thomas Joiner and is outlined in Why People Die By Suicide. The theory consists of three components that together lead to suicide attempts. According to the theory, the simultaneous presence of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness produce the desire for suicide. While the desire for suicide is necessary, it alone will not result in death by suicide. Rather, Joiner asserts that one must also have acquired capability to overcome one's natural fear of death.

The Suicide Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R) is a psychological self-report questionnaire designed to identify risk factors for suicide in children and adolescents between ages 13 and 18. The four-question test is filled out by the child and takes approximately five minutes to complete. The questionnaire has been found to be reliable and valid in recent studies. One study demonstrated that the SBQ-R had high internal consistency with a sample of university students. However, another body of research, which evaluated some of the most commonly used tools for assessing suicidal thoughts and behaviors in college-aged students, found that the SBQ-R and suicide assessment tools in general have very little overlap between them. One of the greatest strengths of the SBQ-R is that, unlike some other tools commonly used for suicidality assessment, it asks about future anticipation of suicidal thoughts or behaviors as well as past and present ones and includes a question about lifetime suicidal ideation, plans to commit suicide, and actual attempts.

In colleges and universities in the United States, suicide is one of the most common causes of death among students. Each year, approximately 24,000 college students attempt suicide while 1,100 students succeed in their attempt, making suicide the second-leading cause of death among U.S. college students. Roughly 12% of college students report the occurrence of suicide ideation during their first four years in college, with 2.6% percent reporting persistent suicide ideation. 65% of college students reported that they knew someone who has either attempted or died by suicide, showing that the majority of students on college campuses are exposed to suicide or suicidal attempts.

References

- ↑ Archives of Suicide Research, 1997, vol. 3, pp. 139–151

- 1 2 3 4 O'Carroll et al. (1996). Beyond the Tower of Babel: A nomenclature for suicidology. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 26(3), 237–252.

- 1 2 Silverman MM, Berman AL, Sanddal ND, et al. Rebuilding the Tower of Babel: a revised nomenclature for the study of suicide and suicidal behaviors. Part 1: background, rationale, and methodology. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2007; 37:248–63.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Silverman MM, Berman AL, Sanddal ND, et al. Rebuilding the Tower of Babel: a revised nomenclature for the study of suicide and suicidal behaviors. Part 2: suicide-related ideations, communications, and behaviors. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2007; 37:264–77.

- ↑ Posner K, Oquendo MA, Gould M, et al. Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment (C-CASA): classification of suicidal events in the FDA's pediatric suicidal risk analysis of antidepressants" Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:1035–43.

- ↑ Thomas Niederkrotenthaler; Marlies Braun; Jane Pirkis; Benedikt Till; Steven Stack; Mark Sinyor; Ulrich S Tran; Martin Voracek; Qijin Cheng; Florian Arendt; Sebastian Scherr; Paul S F Yip; Matthew J Spittal (18 March 2020). "Association between suicide reporting in the media and suicide: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 368: m575. doi:10.1136/bmj.m575. PMC 7190013 . PMID 32188637.

- ↑ Leenars, A. A. (2004). Psychotherapy with suicidal people. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- ↑ Heilbron, Nicole; Compton, Jill S.; Daniel, Stephanie S.; Goldston, David B. (2010-06-01). "The Problematic Label of Suicide Gesture: Alternatives for Clinical Research and Practice". Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 41 (3): 221–227. doi:10.1037/a0018712. ISSN 0735-7028. PMC 2904564 . PMID 20640243.

- ↑ Fairbairn, Gavin J (1995). Contemplating Suicide: The Language and Ethics of Self-Harm. London: Routledge. p. 34. ISBN 978-0415106061.

- 1 2 3 Olson, Robert (2011). "Suicide and Language" (PDF). Centre for Suicide Prevention. InfoExchange (3): 4. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ↑ "Best Practices and Recommendations for Reporting on Suicide" (PDF). reportingonsuicide.org.

- 1 2 Lebacqz, K. & Englehardt, H.T. (1980). "Suicide and covenant" . In Battin, M.P. & Mayo, D.J. (eds.). Suicide: the philosophical issues. New York: St. Martin's. p. 672. ISBN 978-0312775315.

- 1 2 Beaton, Susan; Forster, Peter; Maple, Myfanwy (February 2013). "Suicide and Language: Why we Shouldn't Use the 'C' Word". In Psych. 35 (1): 30–31.

- 1 2 3 4 Sommer-Rotenberg, D. (11 August 1998). "Suicide and language". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 159 (3): 239–40. PMC 1229556 . PMID 9724978 . Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ↑ Silverman, M.M. (October 2006). "The Language of Suicidology". Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 36 (5): 519–532. doi:10.1521/suli.2006.36.5.519. PMID 17087631.

- ↑ "Reporting on Suicide: Recommendations for the Media" (PDF). Suicide Prevention Resource Center. 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-30. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ↑ "What's in a word? The Language of Suicide" (PDF). Alberta Health Services. 2009. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ↑ Wallace, S.E. (1999). "The Moral Imperative to Suicide". In Werth, J.L. Jr. (ed.). Contemporary Perspectives on Rational Suicide. Philadelphia: Taylor & Francis. pp. 48–53. ISBN 978-0876309377.

- ↑ Ball, P. Bonny (2005). "The Power of words". Canadian Association of Suicide Prevention. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ↑ Preventing suicide : a resource for media professionals (PDF). Geneva: World Health Organization. 2008. p. 8. ISBN 978-92-4-159707-4.

- ↑ Beck, A.T.; Resnik, H.L.P. & Lettieri, D.J, eds. (1974). "Development of suicidal intent scales". The prediction of suicide. Bowie, MD: Charles Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0913486139.

- ↑ O'Connor, R.C.; Platt, S. & Gordon, J., eds. (2011). "Challenges to Classifying Suicidal Ideations, Communications, and Behaviours". International Handbook of Suicide Prevention: Research, Policy & Practice . Oxford: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 18–21. ISBN 978-0470683842.

- ↑ Brenner, L.A.; Silverman, M.M.; Betthauser, L.M.; Breshears, R.E.; Bellon, K.K.; Nagamoto, H.T. (2010). "Suicide Nomenclature – 2010 Suicide Prevention Conference" (PDF). Denver: Department of Defense; Defense Centres of Excellence for Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- ↑ Brenner, L.A.; Breshears, R.E.; Betthauser, L.M.; Bellon, K.K.; Holman, E.; Harwood, J.E.; Silverman, M.M.; Huggins, J.; Nagamoto, H.T. (June 2011). "Implementation of a suicide nomenclature within two VA healthcare settings". Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 18 (2): 116–28. doi:10.1007/s10880-011-9240-9. PMID 21626353. S2CID 22877623.

- ↑ Centre for Suicide Research (September 2012). "Media and Suicidal Behaviour: Guidelines and other information". University of Oxford. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- ↑ Media Guidelines for the Reporting of Suicide: 2009 Media Guidelines for Ireland (PDF). Samaritans Ireland. 2009.

- ↑ IASP Task Force – Suicide and the Media. "Media Guidelines & Other Resources". International Association for Suicide Prevention. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ↑ Suicide Prevention: Guidelines for Public Awareness and Education Activities (PDF). Government of Manitoba. 2011.

- ↑ "New Guidelines Developed to Promote Responsible Media Coverage of Suicides". Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. March 2007. Retrieved 15 May 2013.